Fiddle Reef Remembered:

Integrating Artistic and Other

Modes of Inquiry

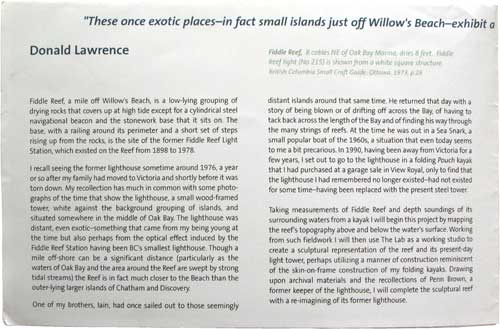

Donald Lawrence

Thompson Rivers University

01 In a footnote to the preceding essay, "Re-Visioning the Visual: Making Artistic Inquiry Visible," W.F. Garrett-Petts articulates three modes by which artists might engage in interdisciplinary research, working with colleagues in the humanities and social sciences. The third of these proposed modes, the "Integrated" model, is one "where the artist works with a particular research group, becoming in effect a co-researcher by committing skills, insights and art production to the research findings."

02 It was in such a manner as this that I was involved for a number of years with Garrett-Petts (Literature, Criticism), David Maclennan (Sociology) and Helen MacDonald Carlson (Early Childhood Education): we carried out a community-based storymapping project with several research assistants coming from our various disciplines (as part of a broader SSHRC Community and University Research Alliance (CURA) project to investigate the "Cultural Future of Small Cities"). [1] As much as the research opportunities afforded by artists' involvement in such projects may seem obvious (or are otherwise articulated elsewhere in this volume), such collaborations are not without their challenges. My role as an "integrated" artist/researcher in the storymapping project was not one in which I created artistic works of my own, so that the project was inevitably competing for my creative and other professional attention. Over time, however, and in hindsight, I have come to understand that there is the potential for an artist's own work to grow and expand as a direct result of such collaborative and interdisciplinary research, even if the manner in which that happens may not be apparent in the moment of working as part of a multi-disciplinary research team. The significance of this realization was in foregrounding the potential for visual artists to offer significant contributions to areas of academic inquiry in a manner that has reciprocal benefits to their own artistic practice. The Small Cities CURA's interest and my own interest in maps and mapping provide a specific instance of such commerce between art and academe.

03 Aside from my background as a visual artist and art teacher, I brought to the storymapping projects a long-standing interest in maps, in particular nautical charts that I use while sea kayaking. It was in 2005, in the same year that our storymapping project was coming to a close, that I recognized I was regularly using mapping for something other than coastal navigation, that mapping practices were playing a significant role in each of my bodies of work exhibited that Fall. A simple overview of these projects readily shows this. Torhamvan/Ferryland, at Vancouver's Contemporary Art Gallery, was a complex installation derived in part from maps that I had surveyed/drawn at the site of the 1926 wreck of the S.S. Torhamvan at Ferryland, Newfoundland. These maps constituted a survey of the quarter-mile long reef upon which the wreck lies—the shape and topography of the reef extrapolated from measurements and bearings taken from one prominent rock or piece of the wreckage to the next. "The Kamloops Archipelago," an installation created for Court House (itself an interdisciplinary forum bringing together an international group of artists and other researchers), that I coordinated in Kamloops drew upon informal research surrounding existing geological maps of the Kamloops area toward a re-imagining of Kamloops' ancient geological past as an island archipelago (Kamloops is now a semi-arid desert in the interior of British Columbia). In this work a landscape construction featuring several off-shore islands wove in and out of the small rooms that made up the judge's chambers in Kamloops' former law courts. Most closely aligned to the methods of our storymapping project—and suggestive of the manner in which my artistic practice was affected by my "integrated" involvement in that research project—was the inclusion of a storymap created by my father in "The Drumheller Albertosaurus" for yet another exhibition, Proximities: Artists' Statements and Their Works at the Kamloops Art Gallery. My father's map, together with an accompanying video narration, provided a form of personal documentation and storytelling related to my elder brother's discovery of a fossilized dinosaur femur and the significance of that as a family artifact. [2] Through the accumulated items that made up "The Drumheller Albertosaurus" (my father's map and video, other family documents, the bone itself, and some existing artworks) I sought to explore the possibility of the dinosaur bone as a latent source behind much of my artistic practice—in a manner akin to the idea explored here, that the work of our storymapping project is likely a latent source—a prompt—for the prevalent use of mapping in much of my current work.

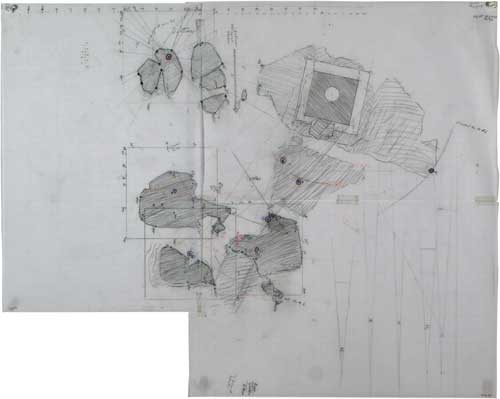

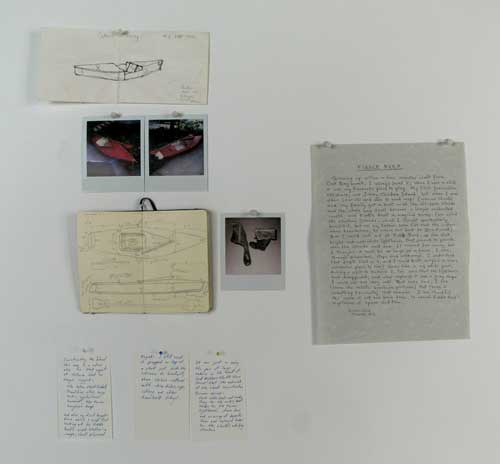

"Fiddle Reef, Remembered,"

(detail)

preliminary drawing, pencil on paper, 39cm x 46cm, 2006.

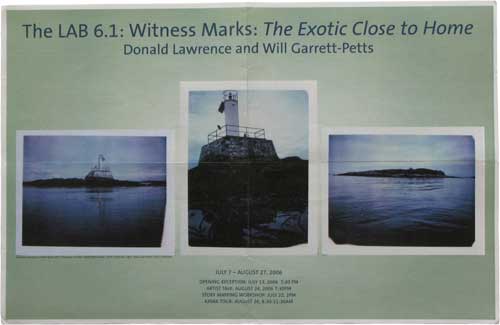

04 Of my exhibition projects around this time, "Fiddle Reef, Remembered," created during a residency at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria during the summer of 2006, is the one that most directly and extensively involves mapping. This project, in the Gallery's project space, "The Lab," was part of a larger project, Witness Marks: the Exotic Close to Home, that saw Garrett-Petts creating a video/installation work of his own ("Catch and Release") and the two of us together engaging the community in ways that stemmed directly from the CURA storymapping projects. "Fiddle Reef, Remembered" constituted a mapping and reconstruction (by way of models) of the site of the former Fiddle Reef light station and the imaginary reconstruction of the lighthouse off the Victoria waterfront, as I recall it from childhood. Mapping practices were essential not just as a preliminary stage toward the construction of a sculptural model of Fiddle Reef; rather, the sculpture was itself inherently map-like by way of its contour and relief. Through the planning stages of this project and carrying on after its completion I put together numerous statements related to the Fiddle Reef project: an initial project description to Lisa Baldiserra, the Gallery's curator; a synopsis of the project for Vivian Skinner, Aids to Navigation officer at Victoria's Coast Guard base toward the use and exhibition of archival material; texts for two separate exhibition brochures; a detailed and illustrated technical description of the completed work prepared for Baldiserra in response to some questions from her about the work; and as part of a proposal to the British Columbia Arts Council for a grant that would allow for the full-sized realization of the folly-like reconstruction of the lighthouse that was imagined through the Lab project.

Witness Marks: The Exotic

Close to Home, exhibition

brochure/posture

(poster, above and inside statement, below), AGGV, 2006

05 The construction of the Fiddle Reef model was to be realized entirely within The Lab and through the seven–and–a–half weeks of the exhibition period. The majority of my time through these weeks was spent in The Lab, mixing the tasks of studio production with a regular and ongoing interaction with visitors. At times such interaction would consist of just a casual comment or two and at other times the visitors and I might engage in any manner of discussions about the works being produced, places of shared or individual interest or various other topics related to the ostensive subjects of Garrett-Petts' or my own work. Through several such interactions visitors would create storymaps of their own, which were then tacked to the wall, taking their place among the items on display. Such activity made The Lab not only a space for creating and displaying work; it was also a space of performance. In a manner that would not occur in more conventional academic settings there was an intense engagement with a broad public not after the completion of a research/creative work but, rather, during its conception and realization.

06 Aside from arriving at The Lab with one preliminary sketch and from having conducted research in the Coast Guard Archives, I made a decision to not otherwise pre-plan or in any way pre-fabricate any components of the work (both of which are a common part of my regular installation practice). Through the duration of the exhibition and right up to its last day, the space of The Lab was a workspace, increasingly filled with salvaged and scavenged objects, the model, and numerous maps, Polaroid photographs, pieces of writing and other documents. It is a detailed catalogue of these items and the sequential reasoning behind their selection/creation that the illustrated technical description created for Baldiserra—a form of artist's statement—presents. [3] In accounting for the manner in which the main construction of the reef (a small islet) and lighthouse are constructed almost entirely from items gathered at thrift stores and garage sales, with a folding ironing board as the central underlying support, the statement indicates that:

I came upon the ironing board at the Willow Antique Mall in Chemainus while searching through thrift/used shops for an appropriate table. In addition to having a light, potentially floating appearance the ironing board also has the characteristic of folding up in a manner somewhat akin to my folding kayaks … On the same excursion that I found the ironing board, I came across a pair of hip waders in the Good Neighbours Thrift Store in Duncan; the hip-waders' rough rubber surface suggested the wet rocks of such intertidal outcroppings as Fiddle Reef. A thinking-together of these various instances suggested the relevance of acquiring and bringing together items from thrift shops and garage sales as a means of recalling a searching activity that was always important to me while living in Victoria and through which this current project would ensure that I moved throughout the city and not only back and forth to the islands.

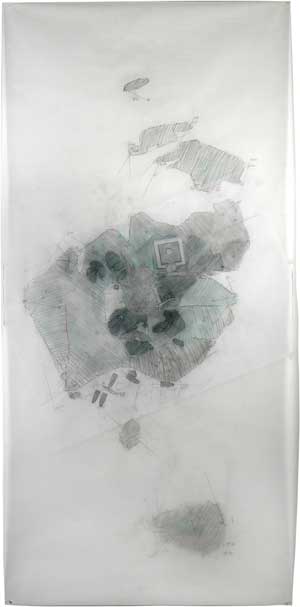

"Fiddle

Reef Remembered," installation view.

Witness Marks: The Exotic Close

to Home, The

Lab, AGGV, 2006.

"Fiddle Reef, Remembered"

(two detail views),

mixed media construction, 190cm x 195cm x 140cm, 2006.

07 If such activity and manner of sculptural assemblage speaks to the urban side, the 'Close to Home' aspect of Witness Marks, the hand-drawn maps that accumulated around the space of The Lab (some as very large drawings) speak to the engagement with the 'Exotic' part of the equation, of time spent on Fiddle Reef. Of the maps, I detailed in the illustrated statement the way in which:

The "mapping" stage of this project (the first stage once in "The Lab") involved a combination of fieldwork on and around Fiddle Reef and the creation of large-scale, hand-drawn maps (primarily) in The Lab. The maps show three states of the tide (as detailed in the individual map descriptions below): "near high tide," "near low tide," and "mid tide" (the stage represented in the sculpture). This was a process of personal mapping, essentially a vernacular manner of mapping derived from navigational practices common to kayaks and other small boats. Such mapping required a few basic principles that are evident in the various notebooks and maps:

• A number of readily identifiable reference points around the reef (rock high points, metal fittings set into the rocks, and toppled concrete piers) were selected. From these reference points, compass bearings were taken to the outer corners of the tower base's railings or to the central vertical axis of the present light tower or to one of the other reference points. In theory, any two such measurements would locate the reference point in relation to (the more easily measured) structure of the light tower's base. As with locating a kayak's location off-shore, however, a location is confirmed/inferred through a process of triangulating and averaging three or more such bearings.

"Fiddle Reef Map, near high tide" (underlay for map to follow),

pencil on taped vellum sheets, 55cm x 69cm, 2006.

Fiddle Reef, Remembered, hand-surveyed/drawn map,

pencil on vellum, with underlay, 164cm x 92cm, 2006.• Measurements of the tower base were taken as a means of establishing a basic set of known reference points (equivalent, in kayak navigation, to deriving some known measurement from a nautical chart).

• Measurements distances between two of the key reference points and to the tower base were taken to check against the triangulated mapping.

• Vertical measurements (elevations) were taken by using a paddle (its shaft and blades marked off to function as a ruler) in relation to a fixed elevation (one of the tower's stair landings) and the horizon. From any given reference point a vertical measurement of the paddle (i.e.. from where it rests on the rock to one of its measured markings) represents the distance below the stair landing when the landing and the horizon are viewed at the same level with respect to one another. I don't know of any particular surveying principle/technique/instrument that this method corresponds to (but would guess that there is one); it simply seemed a good idea. In kayaking, some distances (i.e., to the visible horizon) are approximated by knowing the height of the paddler's eye-level above the water. While this is not quite the same procedure, it is suggestive of the simplicity of the principles involved.

08 In two respects—first by way of simple analogy/description and, second, through the care for detail—this description situates my creation of this map in the vernacular language of a kayaker's interest in navigation, terminology and spatial comprehension. In this statement, and in a manner that parallels the function of the installation's various components, such detail affords a complement to the whimsy that is presented by the sculptural construction, where the sole of a rubber boot comes to represent sea-coated rocks or where a variety of household furnishings and knick-knacks become the underlying structure of the otherwise "exotic" island.

09 The vernacular response, an individual's personal inflection on notions of place, is what Garrett-Petts, MacLennan, myself and others sought out through the community members' involvement in the CURA storymapping project. Such an approach was extended to the Witness Marks project. Drawing upon the CURA work, Garrett-Petts and I invited the Victoria public to convey their own stories of the islands of Oak Bay (or similar places) where Fiddle Reef and Jimmy Chicken Island are located—Jimmy Chicken being the site of Garrett-Petts' video installation "Catch and Release." Their stories intermingled with the other items on display, with it becoming difficult to distinguish at times any boundary between what Garrett-Petts and I put forward and the community contributions. One particular grouping of items emerged, that Baldiserra and I both considered to be a condensed expression of many of my interests in the work—thereby forming something of a self-referential statement for the project as a whole. This particular grouping of items included some of my own sketches, Polaroids and notes but also a narrative account of Fiddle Reef. This was a contribution from Anne Gee, mailed to us from Masset, on the Queen Charlotte Islands. Gee, the sister of Jane Pallin who regularly visited The Lab during our project, has held a long fascination with the islands of Oak Bay, and Jimmy Chicken in particular. Recollecting a time several decades earlier, she wrote:

Miscellany on

wall, including Anne Gee's "Fiddle Reef" letter,

Witness Marks: the Exotic

Close to Home, The Lab,

AGGV, 2006.

My first fascination, off shore, was Jimmy Chicken Island; but when I was older (11 or 12) and able to read maps (marine charts) and my family got a boat — all the off shore islands and the whole bay itself became a larger enchanted world, and Fiddle Reef a magical name.

Of Fiddle Reef in particular she recalled:

the stout bright red-and-white lighthouse that seemed to preside over the islands and sea. It seemed far away, but I thought that it must be as large as a house; I saw, through binoculars, steps and walkways. I understood that people lived in it, and I could not imagine a more wonderful place to live!

10 That Anne Gee's letter, arriving from the distant Queen Charlotte Islands and recalling an also distant time, could so closely mirror what I understood my sculpture and maps to be about struck me as an opportune moment of creation/research. Her letter, tacked on the wall amongst some of my notes, provided a statement for the work as apt as any that I might have created myself—the artist's statement as a "Readymade," or chance occurrence that imparted the same inflection in The Lab as a piece of found text in a Surrealist composition. In such respects the presence of Anne Gee's letter offered a direct parallel to the serendipity that was built into each of the sculptural island's structural components. Like Anne Gee's story, those domestic objects came unexpectedly, often surprisingly, in thrift stores and garage sales, and, like Gee's story, they found their way into the work. Such is the surprise that might emerge from unplanned moments of collaboration and interactivity.

11 Considered in such terms, this project, and the manner in which it has followed from the earlier CURA mapping projects, invokes the desire offered by Sarah Eldridge—and paraphrased by Garrett-Petts in his preceding essay— to have statements (what she prefers to call the "'art statement'" rather than "artists' statements") "as emerging from the art and not just as afterthoughts or obligatory postscripts to the creative act. In the instance of "Fiddle Reef, Remembered" this comes about by way of a hybrid manner of working that is informed by but not encumbered by research methods of the Humanities and Social Sciences as they have been used in the form of storymapping.3 As such, a consideration of the CURA storymapping project, Witness Marks, and those other exhibition projects that I have mentioned, provide an instance of what can be gained by working across disciplines.

Acknowledgement

Research for this essay was supported by a Community-University Research Alliance Grant, a program of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Notes

[1] See David MacLennan, et al., "Vernacular Landscapes." See also, Robin Laurence, "Urban Images."

[2] The Court House project and the international workshop project Artist Statement: Artistic Inquiry and the Role of the Artist in Academe (organized by Garrett-Petts and Nash) were coordinated to take place in Kamloops in concert with one another and during Proximities: Artists' Statements and Their Works as a means of the three projects together providing an in-depth exploration of modes of artistic research.

[3] See Donald Lawrence, "Around Fiddle Reef."

Works Cited

Robin Laurence, "Urban Images: This Place Right Now." Ed. Trish Keegan. Urban Insights. Kamloops: The Kamloops Art Gallery, 2005. 23-47.

Lawrence, Donald. "Around Fiddle Reef: 'Fiddle Reef, Remembered': Materials, Processes, and Related Thoughts." DVD. In Artists' Statements and the Nature of Artistic Inquiry. Ed. Rachel Nash and W.F. Garrett-Petts. Spec. Issue of Open Letter Series 13, No. 4 (Fall 2007).

David MacLennan, W.F. Garrett-Petts, Donald Lawrence, and Bonnie Yourk. "Vernacular Landscapes: Sense of Self and Place in the Small City." The Small Cities Book: On the Cultural Future of Small Cities. Ed. W.F. Garrett-Petts. Vancouver: New Star Books, 2005. 145-162.