Lost Data, 2

Barry Mauer

01 This article is the second part of on ongoing series about lost data. The first part, titled "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," sought to establish the growing impact of lost data and proposed the establishment of a monument as a healthy response to the problem. This article covers some of the same subjects but also considers steps to implementing the monument.

02 The loss of a computer hard drive or a family photo album, the loss of a relative's memory to Alzheimer's, an archive wiped out by disasters (9/11, Katrina), the loss of languages worldwide: all of these are data losses. They can alter the lives of those who experience them. They may affect people as profoundly as the death of a loved one. For the most part, however, we do not mourn these losses, and rarely do we accord them the level of public attention we do other losses such as the deaths of soldiers in war. In this article, I argue that there are significant personal and social benefits to be gained by mourning lost data. Furthermore, I suggest some ideas toward implementing a monument to lost data to support this mourning.

03 Mourning is a process of decathexis, or separation from the lost object or person, which frees up psychic energy to reconnect with other things and people. Mourning also enables the mourner to retain an image of the lost object or person as a guiding force.

The monumental function of architecture included mourning, understood as the collective version of the psychology of identification—the formation of the superego in an individual through the internalization (introjection) of ego-ideals. Monumentality was responsible for maintaining a sense of national identity from one generation to the next (hence the mourning by one generation for the loss of the previous generation, back to the Founding Fathers). (Ulmer, Lusitania 10)

The Supreme Court, which interprets the founders' intentions, functions in theory as a living monument to the founders. Through mourning, we aim, in theory, to do what our selected forbears would have wanted us to do. Some Christians have literalized this form of introjection by asking "WWJD?" (What would Jesus do?)

04 Monuments acknowledge the historical forces that have formed us; they also play a role in re-forming us. Mourning transforms social and neural networks, allowing new meanings to flow in us and among us. Americans' relationship to the World Trade Center site following the attacks of 9/11 is a case in point.

... the WTC has become a social hybrid, part object, part subject, able to act upon and for people, as if animate... Latour found that hybrids trace and enact social networks ... To be vital, a monument must exist within an actual, present-oriented network of relationships. (Nelson and Olin 6)

Gregory Ulmer's work on electronic monuments highlights how much choice is available in terms of who can memorialize, what to memorialize and how to memorialize. His book, Electronic Monuments, is a guide for using monuments to further education and self-empowerment in an electronic age: "The long-range goal is to 'improve the world'; or, if not to improve the world, then to understand in what way the human world is irreparable" (Ulmer xxxiii). The desire to improve the world, and the recognition of our limits to do so, go hand-in-hand throughout his work.

05 Monuments preserve memory and are thus a form of archive. Derrida makes a point about the political power of archives: "There is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation" (Derrida 4). The Internet and its social-networking practices enable any wired group to practice monumentality. Ulmer states that, "the time is right for the democratization of monumentality" (Ulmer, Electronic Monuments xv). The exemplar of this movement to democratize monumentality is Cleve Jones and the NAMES project, founders of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, inspired by the death from AIDS of Jones' friend, Marvin Feldman, a Jewish homosexual whose father had helped liberate the Nazi death camps (Jones xiv). The AIDS Memorial Quilt, composed of thousands of squares contributed by mourners, has proven that a marginalized minority, using basic strategies of social networking, can empower the grieving and transform the culture's values.

06 What can be monumentalized? According to Ulmer, "any event of loss whose mourning helps define a community" (Ulmer, Electronic Monuments xxxiii). Currently, as Ulmer points out, the most publicly acknowledged communal losses are the deaths of soldiers in wars. As a result of efforts by MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) to memorialize deaths caused by drunk driving, The Names Project, and those who constructed the spontaneous memorials after 9/11, we are witnessing an emergence of monumentality in new forms and in new contexts, beyond the parameters of church and state. Ulmer refers to these monuments as "abject" because they re-value that which is devalued.

07 Innovations in monumentality have the potential to transform personal identities, social values, and major institutions. Yet public involvement in abject monumentality is still limited; resistance to participation is due in part to a widespread and determined faith in progress and a fear of confronting loss (major themes in George Bataille's work). In other words, many people prefer to deny the impact that loss has on them and prefer to believe that we can use technological means to prevent future losses.

08 Belief in progress, with its attending emphases on limitless growth, technological problem solving, and projection onto others ("it's not my problem"), is in many ways the dominant civil religion in the United States; by contrast, mourning requires acceptance of our limitations, acknowledgment of irretrievable loss, and potentially uncomfortable self-reflection. Overcoming the denial around the inevitability of loss is one purpose of Ulmer's work and my work here.

09 The "sacredness" of data loss is not yet recognized widely in our society. While certain kinds of losses—the deaths of soldiers—are considered sacred, as inevitable losses made in order to secure our values, other kinds of losses, such as data loss, are not only treated as abject but are dismissed as exceptions, as problems that are "soluble" but have not yet been solved.

10 A typical expression of this attitude can be found in the Popular Mechanics issue of December 2006, in an article titled, "The Digital Ice Age." In it, the writer, Brad Reagan, recounts his visit with Ken Thibodeau, the head of the National Archives' Electronic Records Archive. After admitting that the avalanche of electronic materials coming to the archives is unmanageable—"We don't know how to prevent the loss of most digital information that's being created today" (96)—Thibodeau discusses enormous technological efforts to solve the problem. Lockheed Martin, for example received a $308 million dollar contract to try to solve it, money awarded despite a government researcher telling Thibodeau that "Your problem is so big it's probably stupid to try to solve it" (97).

11 Though few of the technical "fixes" seem promising—because technology and software keep changing, the quantity of data keeps exploding exponentially, and so on—the technical solution is the only one getting attention in Popular Mechanics and elsewhere. The mania for a solution, even when presented with clear evidence of the futility of searching for any ultimate solution, represents an ideological blind spot, similar—though not as extreme—to the fruitless searches in times past for the philosopher's stone and a perpetual-motion machine. There is now a single-minded refusal to accept at least some failure, even a modest amount, within the dominant (i.e., techno-progressive) discourses about data loss. Until we can move beyond this refusal, we will not be able to move to the next question; if we are bound to lose huge quantities of data, what do we, as a society, do to mourn this lost data?

12 Essentially, our values, as represented by Popular Mechanics, are still positivist. As I noted in "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," there is no quarrel between those who seek to recognize data loss as a worthy subject for collective mourning and those who are engaged in technical and administrative efforts to preserve more data. Indeed, there should be mutual recognition, admiration, and respect between the two groups.

13 Data loss may occur over time (as in the slow fading away of the ink from the pages of the Declaration of Independence) or it may occur all at once—catastrophically—as in the hard drive crash or the 9/11 attacks or the floods that followed Katrina. Our age of mass data storage tends to produce more catastrophic losses. Paul Virilio, whose "Museum of Accidents" inspires this project (Virilio, Reader 255), noted that "to invent the train is to invent the train accident of derailment" (Virilio, Accident 10). The term "crash," as Michael Jarrett pointed out to me during the "Imaging Place" conference (Gainesville, 2007), marks modern failures ubiquitously and is appropriate here to describe the general condition of risk, loss, and trauma in modernity. The term "crash" applies to hard drives failing; train, airplane, and car accidents; market collapses; personal and societal failures, and so on. Instead of seeing all such crashes as "bad," Jarrett noted that we can accept them with a sense of juissance (similar to the mood at an Irish wakes or in New Orleans wakes). We can accept lost data not only because denial is unhealthy but also because data loss allows other things to grow.

14 Paradoxically, death and loss allow for life. The philosopher Peter Steeves discusses this paradox in Heidegger's work. In the river Lethe, living things are made to forget as they cross over. Logos is understood as truth, but literally it is the unforgotten. Heidegger is concerned about what we are forgetting when we remember something else. The Enlightenment created a situation in which the lights are always on and there is no sleep. When everything is in books and nothing is forgotten, there is no wisdom, only information.

This is the risk of perpetual wakefulness, perpetual life: madness. And it is the legacy of the Renaissance. With light shown everywhere—the light of reason, the stage set for the Enlightenment's light of knowledge—the Dark Ages were over, but at what cost? With the lights always on, no one ever sleeps. How can one conceal oneself before that which never sets? Knowledge at all costs, the banishment of forgetting. It was, as well, the era of movable type, the era of the book: everything would be stored, nothing would be forgotten again. The conceit of the Renaissance was in thinking aletheia, thinking that the truth is found only in the light, in the unconcealing. But aletheia produces insomnia. The light of Reason never dims, and we grow weary. The persistence of memory leads only to warped time, barren landscapes, and madness. (Steeves 191)

As Steeves reminds us, there is some benefit to the living in loss and death. The implementation of the monument to lost data aims to give mourners back some psychic energy so that we can accept loss and connect to the world as it is now.

15 The how of memorializing—theorizing, designing, and implementing new monuments and mourning practices—constitutes the bulk of Ulmer's book and is the focus of the present essay devoted to the implementation of a particular monument: a monument to lost data. Implementation requires an understanding of monuments' social and informational structures.

16 Monuments may contain elements of historical narrative or arguments about right and wrong, but these things alone do not make a monument. A monument is a special kind of archive that makes possible the transformation of loss into sacrifice. A sacrifice is a loss on behalf of something, usually abstract ("our soldiers died for our freedom"). A monument may designate a loss as a sacrifice whether or not it would have been understood as such by the dead or by the grieving (e.g. those early Pilgrims who died in their settlements could not have considered themselves sacrifices on behalf of an American nation that did not yet exist, yet schoolchildren are taught that their sacrifice was essential to the future of the nation).

17 The history of monuments reveals transformation and adaptation. Alois Riegl, charged with creating policy related to monuments in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, "traced a historical development from the 'intentional monument' whose significance is determined by its makers, to the 'unintentional monument,' a product of later events." (Nelson and Olin 2). In the United States, we have examples of each: the Vietnam Veterans' Memorial Wall and Ground Zero of the WTC attacks. Nelson and Olin make the point that we are seeing, increasingly, examples of the latter. Ulmer's work suggests that there is more we can invent.

18 One type of intentional monument Ulmer suggests is an "asterisk" (Ulmer, Lusitania 11). The asterisk is attached to an existing monument.

1) The genre for electronic monuments [is] defined as follows: a) select an existing monument, memorial, celebration; b) select an organization, agency, or other official body as the recipient of the consultation; c) select a theory as the source for the rationale; d) include electronic technology in some way. The new monument is an electronic "asterisk" noting a revision of the existing monument. (Ulmer, Lusitania 11)

In 2006, I produced a chapter, "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," in which I made the case for a monument to lost data to be attached as an asterisk to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC.

As our society transfers its archives from print to digital media, an unintended consequence results; we lose a great amount of data. The effects of data loss can be profound; without access to vital data, our access to history may be severely diminished. Data loss threatens to undermine individual lives and major institutions. This essay discusses the phenomenon of data loss in the age of digital media. I identify the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC as a site of data loss at a national level, and suggest mourning as a means of coping with data loss. To facilitate the mourning of data loss at a national level, I propose a monument to lost data that will be located at the NARA. This monument is to have an on-site component and an online component: a network of memorial entries created by individuals who have suffered data loss. (Mauer 287)

Following the publication, I was asked, "How is the monument to lost data to be implemented?" A key to answering this question lies in revealing the core paradox at work in current archival technologies and practices; the growth of data storage and networking worldwide has created tremendous data losses.

Space radar, infrared photography, carbon dating, DNA analysis, microfilm, digital databases—we have better technology than ever before for studying and preserving the past. And yet the by-products of technology threaten to destroy—in one or two generations—monuments, works of art, and ways of life that have survived thousands of years of hardship and war. This paradox is central to our age. We can access infinite amounts of information on the Internet, but the historical context of it all is escaping us. Globalization may eventually benefit countries around the world; it will also, almost certainly, lead to the disappearance of hundreds of regional dialects, languages, and whole societies. (Stille, inside front jacket)

The rate of change in data storage is exponential. "Humans will likely generate more information in 2008 than we've produced in the cumulative history of our species" ("The Too Much Information Age" 59). Yet as data capacity increases, so does data fragility and the time and money spent on data management. Many institutions are engaged in a losing battle to keep up. One such institution is the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC.

The NARA in Washington, DC is emblematic of the modern data crisis. According to Stille, author of The Future of the Past, this federal agency, which is charged with storing and making available government records, "may have lost more information in the information age than ever before." . . . Stille cites a 1996 study of the NARA concluding "that, at current staff levels, it would take approximately 120 years to transfer the backlog of nontextual material (photographs, videos, film, audiotapes, and microfilm) to a more stable format." (Mauer 291-2)

Paradoxically, the more "progress" we make in data storage, the more data we lose. The purpose of the monument to lost data is to transform such losses into a sacrifice (on behalf of progress). Yet data loss is more than roadkill on the progress highway; it is our existential condition. Humans take years to reach the point when they can read, years more (if ever) to appreciate the wisdom of their elders. Those humans who manage to attain some wisdom will one day lose it to infirmity or death. Archives enable us to pass along data to the next generation, but data itself is not wisdom.

In 1989, systems scientist Russell Ackoff formulated the Data, Information, Knowledge, Understanding, Wisdom hierarchy, which delineates each category, separating raw facts from more useful explanation and interpretation. The hierarchy places the lowest value on data and the highest on wisdom. "Despite this," Acoff says, "the allocation of time and effort in the education system and in the corporate world is inversely related to the value of these things." ("The Too Much Information Age" 59)

Wisdom, according to Ackoff, is "the ability to perceive and evaluate the long-term consequences of behavior. It is normally associated with a willingness to make short-run sacrifices for the sake of long-run gains" (Ackoff 162). A monument is a kind of wisdom shortcut. It puts sacrifices and gains into immediate perspective. Ulmer suggests that abject monuments (e.g., to deaths caused by automobile accidents) might cause us to re-evaluate our behavior, leading us perhaps to judge that our gain—the freedom to drive ourselves around—comes at too high a cost.

19 An apparent paradox of the monument to lost data is its purpose to archivize the losses of archives (and the inevitability of its own decay, fragmentation, and loss). The paradox is resolvable if we consider that the purpose of mourning is to create new social and neural networks that enable us to function despite, and maybe even because of, our losses.

I chose the mushroom/mycelium as the structuring metaphor for the monument because "Fungi play vital roles in all ecosystems, as decomposers, symbionts of animals and plants and as parasites" (Dix and Webster preface). By analogy, the monument to lost data will feed on the decaying matter of our information age, transforming it into something that might be more beneficial to the society. "Mycelium" is also attractive for its homophonic suggestiveness, namely its resemblance to the words "mausoleum" and "museum," which are also repositories for valuable things. The mycelium works well as the poetic structure for the monument to lost data because mycelia permit novel hybrids. In the monument I envision, there will be novel combinations of data loss entries that will lead to new insights about the costs of our collective values and behaviors. I envision the various data loss entries in the monument being linked using the principles of "hyphal fusion," a principle of linkage that fungi employ to share resources. Hyphal fusion permits diverse species of fungi to bond their mycelia together and share resources, and it also leads to the development of new species of fungi (Dix and Webster 15–16). By analogy, I use the principle of hyphal fusion as a poetics for structuring the virtual part of the monument to lost data; diverse data loss entries will be joined and thus will produce, I hope, new insights and possibly new memes for understanding our personal and collective relationships to data. Such linkages do not impede users from exploring the monument's database by using a search engine. (Mauer 308)

After discussing the rationale and proposal for the monument at two conferences in 2007—the Center for New Testament Rhetoric and Hermeneutics Conference in Redlands, California, and the Imaging Place Conference in Gainesville, Florida—further discussions about implementing the monument arose. These discussions revolved around several points:

- The involvement of public agencies (NARA, libraries and universities) and the problem of how to overcome these institutions' potential embarrassment at failing to secure all their data;

- The design of the physical monument at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) building;

- The mourning process, and how the monument might encourage and direct mourning;

- The development of an agency responsible for maintaining the monument and its institutional practices.

The remainder of this essay will address these concerns in order.

1. The involvement of public agencies (NARA, various libraries and universities) and the problem of how to overcome these institutions' potential embarrassment at failing to secure all their data.

20 One participant at the Gainesville conference expressed concerns that the target institution—the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC, as well as libraries and other archives—would be reluctant to host a monument that pointed to their shortcomings (i.e. their failure to preserve all the data entrusted to them).

21 She argued that "the Cristo approach"—enlisting agencies as collaborators—would not work because they would put up too much resistance (out of embarrassment about their losses). She recommended taking a "Yes-Men" or Michael Moore guerilla-theater approach. She suggested putting inflatable mushrooms without permission on the mall in front of the NARA building.

22 I oppose the guerilla approach for several reasons. The most important reason is that a goal of the monument is to prod public archives to assume responsibility for recognizing and mourning collective data loss; these institutions represent the primary sites of collective loss and they are capable of addressing such loss in terms that make sense to the public (e.g. by representing how many volumes were lost). Additionally, one goal of the monument is to impact the institutions themselves by opening space for examination about their "archive fever":

to be en mal d'archive can mean something else than to suffer from a sickness, from a trouble or from what the mal might name. It is to burn with passion. It is never to rest, interminably, from searching for the archive right where it slips away. It is to run after the archive even if there's too much of it, right where something in it anarchives itself. (Derrida 91)

A guerilla-theater approach will likely produce more resistance to the project, not less. Another objection: mourning takes time. People need time to participate in maintaining a monument and time to develop mourning practices. Guerilla-theater actions, while they may gain attention in the short term, do not permit people adequate time to mourn. A final objection: archivists already know that eternal preservation is an impossible dream, yet we rarely hear such sentiments voiced openly. We can address archival problems using positivist methods (i.e. we can lengthen the relatively short lifespan of digital media by using improved materials) without contradicting the fact that no archival media lasts forever.

23 In my conversations with a half dozen archivists and librarians at the University of Central Florida and at other institutions, I have found that all were sympathetic to the idea of mourning data loss. Each one of the archivists I spoke with mourns data loss privately. Their mourning is not expressed collectively, yet they understand the potential benefits of collectively mourning data loss. Their personal sympathy does not automatically translate to institutional action, but we can access it in support of the project.

24 I recommend that the monument be implemented in stages, with smaller archives—local and university libraries—taking up the idea first. Positive publicity may then build to the point that larger institutions, such as NARA and the Library of Congress, may become interested.

2. The design of the physical monument at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) building.

25 The project includes two sites: one physical, one virtual. Because a major purpose of the monument is to bring the community's grief over data loss into view on a national scale, the NARA building in Washington, DC (Fig. 1) is the perfect site for the physical monument because it houses original founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution and it attracts thousands of tourists every year. The monument to lost data will be an asterisk here, marking the sacrifice of data on behalf of our national interest in progress.

Figure 1: The National Archives and Records Administration building in Washington, DC. (NARA).

26 Figure 2 shows a faerie ring of mushrooms connected by mycelia below the surface of the ground. Mushrooms aid in the regeneration of organic material by living on "waste" which is then transformed by the mushrooms into food for other organisms. The monument to lost data feeds on decaying and dead archival matter, transforming it into psychic nourishment than can renew us and sustain us (via mourning).

27 Figure 3 shows the author's rendering of the physical monument—mushrooms superimposed in a faerie ring shape on the NARA rotunda's floor. The faerie ring is an appropriate configuration for the virtual monument as well; because 60% of the population of the United States lives near the coasts, the virtual faerie ring could be represented as a map of the country with mushrooms around the borders and the occasional mushroom popping up in less-populated inland areas.

Figure 2: Mushrooms in a faerie ring.

Figure 3: Author's Photoshop rendering of mushrooms

arranged in a faerie ring around the floor

of the National Archives' rotunda (NARA

image with mushrooms added by the author).

28 Mushrooms feed on decaying matter. The more decaying matter—i.e. the more data loss—the greater the number of mushrooms. To appeal to the weary tourist, the mushrooms should be made of soft material to enable sitting and contemplating (a life-sized model of Rodin's "Thinker" sitting on a soft mushroom might serve as an example of what to do).

29 Communities of mourners share the burden of mourning. When mourners connect to other mourners, they see their stories reflected in the stories of other mourners. Mourning is supported when it occurs within a network that functions like a collective mirror, reflecting to us our values and losses.

30 My hope is that the monument to lost data would help mourners form a community capable of turning private grief into collective wisdom. To that end, the monument should incorporate individuals' contributions, made up of the fragments and phantoms of their lost data. The networked structure of the monument connects one mourner with others. Each mourner will be encouraged to seek patterns in these linkages and to form new relationships with other mourners (similar to the ways in which social networking sites such as Myspace and Facebook allow people to make such connections).

31 In "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," I recommended a process of linking personal monument entries using the principles of "hyphal fusion" in mushrooms. Hyphal fusion allows mushrooms of diverse species to link to one another and share resources; this process can lead to the generation of new species.

The puncept will be the textual version of 'hyphal fusion,' or linkage, in the virtual part of the monument to lost data. It permits patterns to form based on shared terms and can be used in addition to the hierarchical groupings, like the Dewey Decimal System, found in most data archives. The monument to lost data will take terms 'out of context' the way a Google search does, without regard for the topics of the texts being searched; thus the word 'trace' may appear in both scientific works and in art criticism, and can be used to link texts from both discourses. The monument will treat terms that cross discourse boundaries as points of linkage among diverse entries and will present juxtapositions of such entries in order to help people produce new inferences about their data losses. (307)

A monument that places personal losses in relation to each other may lead to our recognition that each loss is part of a larger pattern. The monument to lost data shows us these patterns, just as the Names Project (or AIDS Memorial Quilt) reveals to mourners patterns about our personal relationship to collective death and disease. Data loss is not solely the province of individuals. Collective losses—losses of languages, rituals, rare texts, government data, etc.—affect us as well. Bringing personal and collective data losses into relationship is intended to help individual people as well as communities heal from these losses.

3. The mourning process, and how the monument might encourage and direct mourning.

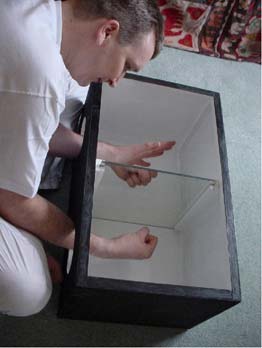

32 "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," I suggested that V.S. Ramachandran's method for treating phantom limb pain can help us understand the effects of data loss and to reduce their negative impacts. Readers expressed some confusion about how the Ramachandran Method relates to mourning lost data. Ramachandran is a neuroscientist who discovered that there are remarkable networks in the brain that can be reprocessed to provide pathways for healing. He writes, "your body image, despite all its appearances of durability, is an entirely transitory construct that can be profoundly modified with just a few simple tricks" (62). In cases involving amputees who feel pain and/or paralysis in a phantom limb, Ramachandran was able to help his patients form new relationships between different areas of the brain, including the visual cortex and the motor cortex; once reprocessed, these relationships allow the amputee a sense of control over the phantom limb. By placing the "good" limb in the Ramachandran Mirror Box (Figure 4)—a box with a mirror that creates the visual illusion of having a matching limb—the amputee sees the missing limb "appear" again. By flexing the "good limb" and watching the reflection, an amputee's brain creates pathways between the visual cortex and motor cortex, and amputees report being able to feel new sensations in the phantom limb. Once the missing limb is "felt" using this method, the amputee continues the treatment for several weeks until the brain re-maps the body with a more realistic picture. Eventually the pain in the phantom limb, as well as the phantom limb itself, is reduced or eliminated as the brain re-maps the body. Ramachandran writes, "It seems extraordinary to contemplate the possibility that you could use a visual illusion to eliminate pain, but bear in mind that pain itself is an illusion—constructed entirely in your brain like any other sensory experience" (58).

Figure 4: The Ramachandran Mirror Box.

«http://www.23nlpeople.com/Phantom.htm».

33 There are several points of analogy between phantom limb pain treatment and the mourning practices I propose for the monument to lost data. The first is that both the Ramachandran Method and the monument to lost data deal with the trauma of loss. The painful memories of lost data can feel like phantom limb pain to the person who lost the data. In "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," I reported that our department secretary had remembered the nested folder structures on her computer after its hard drive crashed and the data was lost. When triggered to recall the data on her computer, the secretary could remember the pathways and folders she had used to retrieve the now-lost data. This recall led to a brief moment of pleasure—the feeling of power one has when knowing how to find something—followed by a longer period of grief upon realizing that the data was gone. The pathways to the data, and the triggering episodes (i.e. "do you remember last year's personnel report?"), leave the data griever with a sense of unresolved pain. The pathways to the data stored in the mind are analogous to the pathways in the motor cortex that remain active after a limb is amputated. In both cases, these feelings can get "stuck." The Ramachandran Box and the monument to lost data are both intended to get the griever "unstuck."

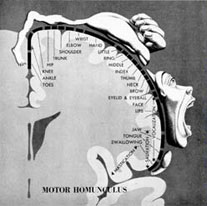

34 Ramachandran made his discoveries about neural processes by finding correspondences between patients' reports about their physical sensations and the Penfield Map (Figure 5), a rendering of the mind's image of the body that stretches across the top of the cerebral cortex.

Figure 5: The Penfield Map (also known as the Homunculus).

«http://www.eatonhand.com/hw/homunc.gif»

35 In the Penfield Map, the body is distorted so that lips and fingers receive disproportionately larger areas of representation in the brain than do other areas, such as the trunk. As people develop awareness of their external memory databases—the books on their shelves and the data on their hard drives—they form maps of these archives internally, maps that share some of the distorted qualities of the Penfield Map. Some books on the shelf, for example, may be disproportionately represented in the mind. Some books may not even appear in the mind's database map. The degree of "pain" that follows data loss may correspond to the degree that the lost data is represented in the mind. For example, the loss of a screenplay that a writer has been composing for the past year will likely produce a much larger degree of pain than the loss of a whole shelf of books that the writer does not remember owning.

36 Additionally, the method of reconnecting to the object of grief in both instances is similar. For the amputee, the Ramachandran Box uses a different sense—visuals—to access parts of the mind connected with tactile feelings. In the monument to lost data, the griever is encouraged to create a representation of his or her own relationship to the lost data that activates other senses. For instance, in the case of missing visual files (i.e. a family photo album), the griever may record an audio description of the photos. To recover from the loss of audio files, the griever may create a piece of writing.

37 Ramachandran's technique can work even when two limbs are missing—for instance, a prosthetic may be used to simulate one of the missing limbs. Whatever the technique, the key to Ramachandran's method is the creation of a new and more accurate "image map" of the body in the mind. Similarly, the monument to lost data provides a more accurate image map of the mourner's archives. For instance, the lost data may have represented hopes for career advancement, or hopes for passing on a family legacy. The mourner contributes to the monument by representing these hopes, and the losses, their work. Mourners may form networks with others who had similar hopes. Grief counselors recommend that people mourning join others who have suffered similar losses.

Social support is critical throughout the entire grief process. It enables the bereaved person to tolerate the pain of loss and provides the acceptance necessary for completion of grief work and reintegration back into the social community. . . . Both psychotherapy and self-help groups (or mutual support groups) benefit from the "helper-therapy principle" (Reissman, 1965), in which the member experiences an enhanced sense of interpersonal confidence, self-worth, and purpose and meaning through being of help to others. (Rando 82)

Healing from data loss progresses when mourners help each other to identify their strengths and resources (i.e. other parts of their legacies survive and can be passed on to the next generation). They also come to accept that data loss is inevitable, which allows them to let go and move on.

4. The development of an agency responsible for maintaining the monument and its institutional practices.

38 In "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data," I suggested that an agency be created to support data mourning. This agency, to be named The Mourning Of Lost Data Foundation (The MOLD Foundation), will be self-supporting and will serve the ongoing needs of data mourners. Organizers will consist of data mourners who have gone through at least some of the mourning process and can assist others who are just beginning. The agency will require the skill and expertise of technicians familiar with archiving and data networking, but considering that those most likely to participate in such an agency are precisely the people with those skills, such people should be readily available.

39 As for the various design elements of the foundation and of the monument (including decisions about explanatory literature for mourners, the network structure of the contributions), these issues should be considered carefully by a group of active data mourners.

Barry Mauer is Associate Professor of English and member of the Texts and Technology Ph.D. Program faculty at the University of Central Florida.

Works Cited

Ackoff, Russell L. Re-Creating the Corporation: A Design of Organizations for the 21st Century. New York: Oxford UP, 1999.

Austin, A. "The Ramachandran Method and the NLP Practitioner." Brain, Mind and Language. 8 July 2004. «http://www.23nlpeople.com/Phantom.htm».

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 1996.

Dix, Neville, and John Webster. Fungal Ecology. London: Chapman & Hall, 1995.

Jarrett, Michael. Remarks to the author. Gainesville, Florida: Imaging Place Conference, February, 2007.

Jones, Cleve, and Jeff Dawson. Stitching a Revolution: The Making of an Activist. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2000.

Mauer, Barry. "Proposal for a Monument to Lost Data." Studies in Writing: Vol. 17. Writing and Digital Media. Eds. Van Waes, Luke, Mariëlle Leijten and Christine M. Neuwirth. Oxford: Elsevier, 2005.

Nelson, Robert S., and Margaret Olin. "Introduction" and "Epilogue. The Rhetoric of Monument Making: The World Trade Center." Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade. Chicago: The U of Chicago P, 2003.

Ramachandran, V.S., and Sandra Blakeslee. Phantom in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind. New York: William Morrow, 1998.

Rando, Therese A. Grief, Dying, and Death: Critical Interventions for Caregivers. Champaign: Research Press Company, 1984.

Reagan, Brad. "The Digital Ice Age." Popular Mechanics. December, 2006.

Steeves, Peter. "There Shall Be No Name." Mosaic 40.2. June, 2007.

Stille, Alexander. The Future of the Past. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2002.

"The Too Much Information Age." Seed. Jan/Feb 2008: 59.

Ulmer, Gregory L. Electronic Monuments. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2005.

—. "Abject Monumentality." Lusitania, Volume 1, 4. Lusitania Press, Inc., 1993.

Virilio, Paul. The Original Accident. Trans. Julie Rose. Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2007.

—. The Paul Virilio Reader. Ed. Steve Redhead. New York: Columbia UP, 2004.