Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 41 (2026)

Opening Lines

Sara Ghazi Asadollahi

Georgia State University

Abstract: This essay argues that the “line” serves as a formal principle through which these film openings map a work’s own formal thinking, extending Tom Conley’s claim that openings establish a geography for spectatorship. Through a close analysis of Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), and Tsai Ming-liang’s Days (2020), it argues that lines—graphic, architectural, and intervallic—anchor structures of framing, duration, and montage where abstraction operates most intensively. The discussion draws from Gilles Deleuze’s cinema books to describe how lines modulate perception, delay action, and generate compositional thought. It further mobilizes Marco Frascari’s notion of drawing as facture to frame Kurosawa’s spatial construction and Irene V. Small’s “organic line” to elucidate Tsai’s seams, thresholds, and adjacencies as topological operations. Taken together, these examples show line as a transmedial method by which cinema composes, reflects, and builds its world.

In Cartographic Cinema, Tom Conley writes that “in its first shots a film establishes a geography with which every spectator is asked to contend...” The opening, for Conley, performs a cartographic function: it draws the coordinates through which the spectator will navigate the film’s world. Building on this insight, I propose that the opening of a film performs a formative mapping—a moment when the film begins to think about form itself. Like the abstract of an article, the opening scene often offers a compressed glimpse of the film’s formal structure, a sketch of how it will unfold, move, and think as it develops. This does not imply that all films enact such a mapping, or that those that do follow a single pattern. Rather, it suggests that certain filmmakers—what Conley, following Deleuze, calls cinema’s “great authors”—use their openings to establish a formative relation between image and structure, revealing how the film conceives its own form.

In this sense, line constructs the film’s visual map, its cartographic weave, or as Tom Conley describes it, its points de capiton, points of stress that plot cinema’s relation to space, history, and being. Yet more specifically, I argue that these points anchor themselves in the film’s form—its structures of framing, duration, and montage—where abstraction operates most intensively.

To pursue this claim, I turn to three films—Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), and Tsai Ming-liang’s Days (2020). What links them is not theme or narrative but their invention of “irreplaceable autonomous forms.” Each film’s opening can be used as a guide to trace how its formal logic takes shape – how an initial form or image sets in motion patterns that later expand into the film’s broader structure and conceptual field.

In Diary of a Country Priest (1951), line appears through the ruled pages of the diary, the crosshatched blotting paper, and the dissolves that overlay writing with image. These textual and visual lines set up diagrammatic structures that carry time, fracture, and rhythm into the film’s visual field. Bresson’s cinema of writing demonstrates abstraction as a form of inscription, where line carries a double force: it constrains and it unfolds, shaping how form develops on screen.

In Throne of Blood (1957), line becomes architectural. The film constructs a space where visibility and invisibility continually exchange—fog, wind, and movement redraw the boundaries of built form. Kurosawa’s castle, and later its ruin, oscillates between solidity and dissolution, as if the architecture itself were breathing. Line here is both constructive and subtractive, carrying breath and fracture together—the principle through which the film materializes abstraction: an architecture of hesitation, delay, and air.

In Days (2020), line appears as interval. A faint reflection cut across a forehead; walls, windows, and thresholds segment bodies into suspended tableaux. Long-takes stretch duration into temporal lines of hesitation. Tsai composes a cinema of waiting, where minimal but decisive lines hold bodies and spaces in resonance.

Across these films, (graphic) line operates as structural force rather than symbolic embellishment. It functions as a transversal abstraction that allows painting, theatre, and architecture to enter fiction film as method. Abstraction in this sense, names a transmedial force, the mutual ground where cinema engages other arts through line, rhythm, and void. The methodological proposal is simple: approach fiction film by tracing its formal logic—here the work of line—as a source of constraint, delay, and force. Take abstraction as a verb; it acts and it unfolds. It shapes gesture, fracture, and fold, revealing cinema as composition in motion, a plane of lines that generate thought.

In Deleuze’s The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, the concept of the line emerges as an axis of transformation, a trajectory that enfolds movement, becoming, and multiplicity. The line is never just drawn; it bends, shifts, and curves into new dimensions, revealing the dynamic forces at play in both material and conceptual forms. In the Baroque aesthetic—which Deleuze positions as a mode of thought rather than a period style—the line ceases marking fixed boundaries. Instead, it becomes a living contour that follows the endless modulation of the fold. Here, the fold is not a metaphor but an operation: the world made of matter that keeps folding and unfolding. The line, then, is both the trace of this folding and the horizon of its potential.

In short, to write of the line is to grapple with its dual nature as noun and verb, as presence and process. The line carries more than a boundary; it sets form in motion, alters perception, bends time, and opens new spatial dimensions. In its abstraction, the line performs the operation of the fold, turning cinema into a field of continual variation. In Deleuze’s Baroque, the line acts as a force of becoming, a vibration traversing the material and immaterial, the visible and the unseen. Here, the line becomes less a mark on a surface and more an event: a moment of folding, a trace of unfolding, a horizon where abstraction continually labors.

Diagrammatic Lines

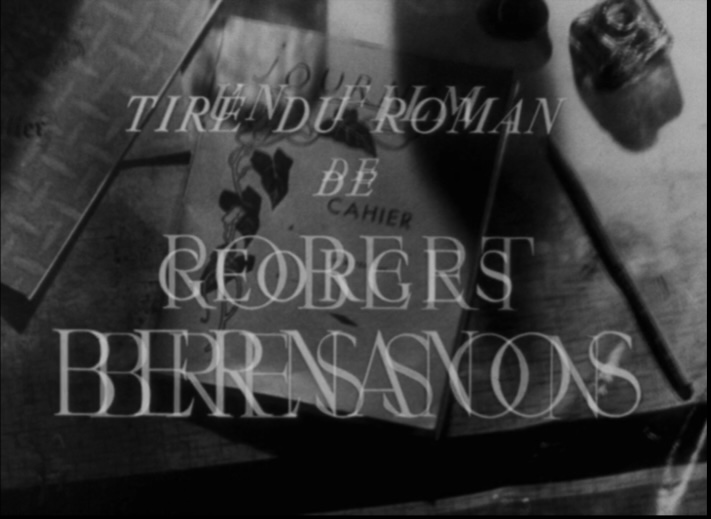

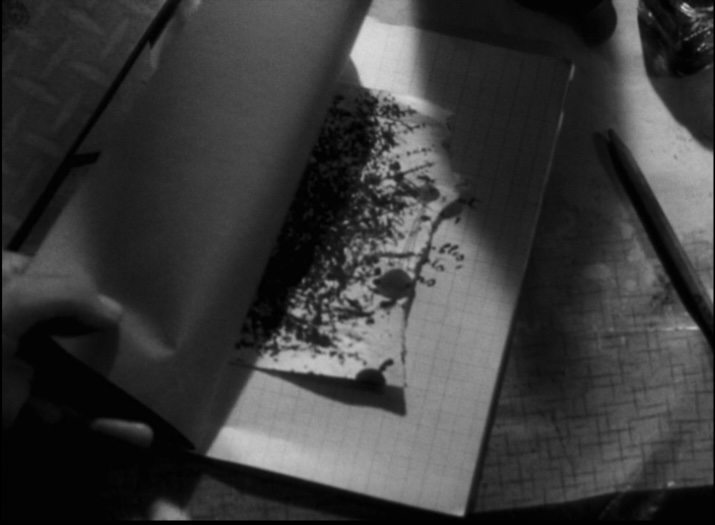

Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951) opens with an intricate choreography of visible and invisible lines: the written lines of the credits, the inscribed text of the diary, and the imperceptible lines produced by cross dissolves that layer imagery with a quiet cinematic fluidity. Alongside these are the graphic lines—the regimented patterns of the paper forming a grid-like background, a diagrammatic system that underpins the chaotic, crosshatched textures of the blotting paper folded within the diary’s pages. It is as if the blotting paper’s chaotic abstraction, unruly yet contained, absorbs and folds the other line types into its dense network. These fractured, unbound lines ripple through the film, shaping its formal and narrative architecture and establishing the film’s geography in the first shots.

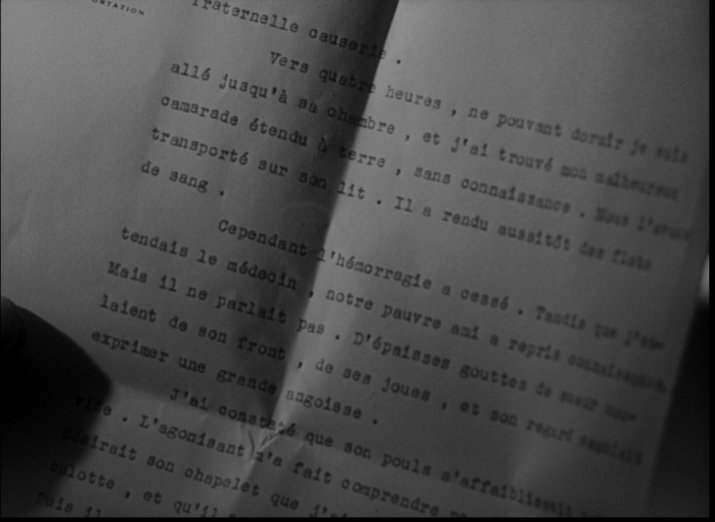

The film—an adaptation of Georges Bernanos's novel of the same name—as Michel Chion notes, portrays “the making of cinema from the 'un-writing' of a novel,” unveils a closed journal abutting ink and pen—together, the quintessential apparatus of handwriting. A hand—the Bressonian signature—enters from screen left, opens the journal, and is followed by a second hand wielding a second pen, thus anticipating without initiating the longhand that inks the filmic text, seemingly. For preceding all priestly penmanship is the film’s opening credits, typographically overlaying the handwriting assemblage, an overwriting concluded—underwritten—with “Scénario adaptation et réalisation de Robert Bresson”; in other words, non-diegetic writing precedes the diegetic. After the credits closing and the journal’s opening, what we see first is a sheet of blotting paper marked by random dots and lines. Abstraction precedes the text—before calligraphic figure or line-bound signification. This small piece of paper—an abstract trace of thought, a residue of diaristic pre-production—at once serves as a rehearsal for inscription, a provisional space where thought and motion converge, illuminating the preparatory gestures that precede writing. Simultaneously, it embodies the essence of the line: the most fundamental unit of visual art and design, a liminal phenomenon poised between presence and potential. Before it becomes text, word, gesture, or thought, the lines on the blotting paper, severed from scenographic content, assert themselves as imprints of a formal process—pure abstraction unburdened by dramatic intent.

These lines, woven through Bresson’s cinematographe, establish a cinematic language that moves beyond representation into a domain of abstraction, where visual and textual elements fold into one another. The opening credits, referencing Bernanos’ novel, while an homage to the source material, become an act of inscription that situates the cinematic within a constellation of media: literature, handwriting, and film. Here, the abstraction of the line becomes paramount, an abstract force shaping the film’s engagement with form.

In Diary’s opening, the invisible gesture, suggested by the lines on the blotting paper, flickers between presence and absence, appearing only to disappear with the movement of the hand, unfolding through erasure. Before the word, there is the line: chaotic, unruly, a site where boredom and violence accumulate. These lines, dispersed across the blotting paper, render writing as a process of exhaustion—a scattering that links the physical act of inscription to the immaterial drift of thought and space. The priest’s diary, like the novel that precedes it, opens with a meditation on boredom—a world “eaten by boredom.” Writing becomes an act of endurance, a fragile refuge from the crushing weight of ennui, a tenuous shelter to sustain a presence against the pull of disappearance. Yet this boredom, tied to the spatial confinement of his parish—“my parish is bored stiff”—echoes a deeper unease, a guilt tied to the “fermentation of a Christianity in decay.” The priest’s unspoken thoughts, volatile and forbidden, escape through the act of writing, their weight bleeding onto the page. In this abstraction, the chaos of lines and dots on the blotting paper mirrors the fleeting and ephemeral nature of his reflections, leaving their trace as a testament to the impossibility of full expression.

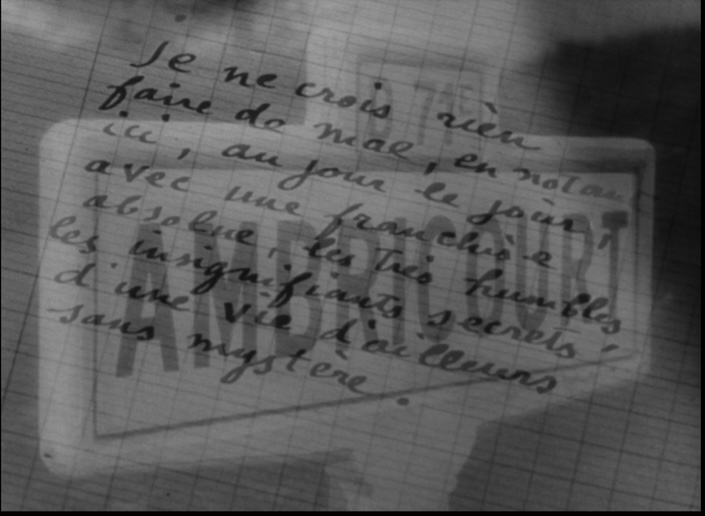

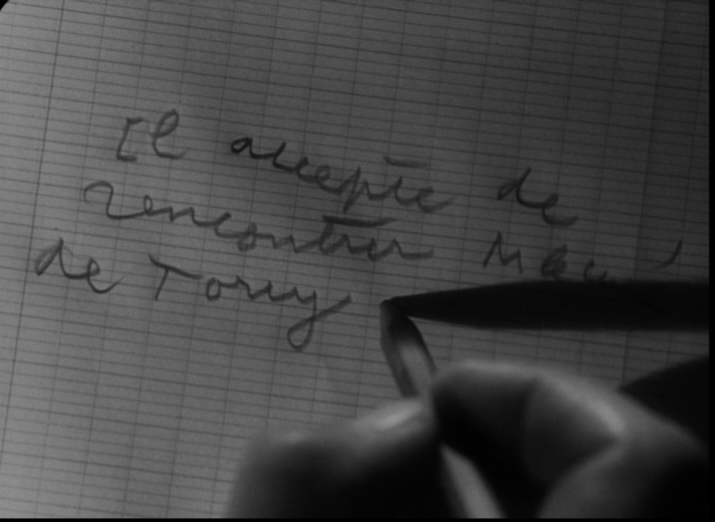

As if repressing its creative potential, the pen-wielding hand removes the blotting paper to reveal a page, the camera slowly zooming in—le cinématographe begins, traversing the imaginary line that folds text, image, camera, and author into a singular gesture. The handwritten text emerges: “I don’t think I am doing anything wrong in writing daily, with absolute frankness, the simplest and most insignificant secrets of a life actually lacking any trace of mystery.” Yet, to “write the simplest and most insignificant secrets of a life” becomes an act laden with guilt and scruple, as he confesses: “when writing of oneself, one should show no mercy.” Here, writing operates as both self-revelation and self-punishment, folding the monotony of boredom into the violence of its own inscription.

Meanwhile, a voice-over imbues the scene with a layer of auditory texture, creating harmonious dissonance. The image then dissolves into a road sign—one for “AMBRICOURT”—signaling a shift in narrative space. The dissolve itself operates as a gesture of movement, shifting from one point to another through ellipsis, erasing the line into another point—what Tom Conley calls being placed “sous rature,’ under erasure.” A close-up of the priest wiping his face, a gesture iterating the blotting paper’s removal, punctuates this opening sequence, thereby closing its formal overture, rendering these marks more than material accidents; they enfold the priest’s inner scruples, his turmoil, and his physical labor, while simultaneously binding the text to the spatial and emotional weight of Ambricourt. The lines, in their abstraction, connect the gesture of writing to the spatio-temporal cinematic gesture, fusing text, image, and movement into a single rhythmic continuum.

Thus Line, in its abstraction, unfolds here through the registration of gesture, text, and space, each cleaved between materiality and cinematic transmutation. Gesture fractures into bodily and cinematic modes: the priest’s hand wiping, writing, repeating, while the film itself dissolves, movement collapsing into erasure. Text wavers between literature and adaptation, Bernanos’s novel fractured into a script where words persist not as dramatic expression but as visual and sonic residue. Space is both physical and screen-bound, Ambricourt rendered in gridded gates and skeletal trees, a site both real and cinematically constructed, enclosing the priest within the architecture of his own undoing. These registers do not merely coexist but inflect one another, modulating the film’s aesthetic of inscription.

In abstracting the gesture, the lines on the blotting paper precede the text already inscribed, existing as an abstract residue of the act to come. The preparation—the cleaning of the pen, the moment the hand poises to write—is withheld, invisible. Yet, we can read through these “lines.” First, they bear the material excess of writing: the spilled ink, the uncontrolled bleed, the matter that overflows before the “proper” word is delivered or inscription takes its form. These lines might also suggest the aimlessness of doodling, a kind of writing without intention, purposeless yet absorbing, a gesture to occupy a mind and hand tethered to monotony. In addition, they enfold the multiplicity inherent in the process of writing—the repeated moments the pen touched the paper, the accumulation of dots merging into lines—a temporal image where gesture and duration converge. A form that enacts what Deleuze calls “the development of time,” that is, not time unfolding as consequence but as pure insistence, and what Jordan Schonig calls “habitual gesture.” However, in the absence of the body, it is the imprint, here the lines, that assume this function—the trace superseding the gesture, the mark standing in for the act.

Thus, Diary troubles the embodiment of gesture. Interspersed with nearly twenty-five close-up journal shots—some showing the act of writing, some scratching, tearing apart the paper—the film shows only a few depicting the priest sitting and writing in medium shot, while in all, the voiceover following the writing creates another detachment. As Bazin observes in the interplay between sound and image in Diary, Bresson’s method achieves “the most rigorous form of aesthetic abstraction while avoiding expressionism by way of an interplay of literature and realism.” The film’s post-synchronized voiceover, detached and flattened, dominates the soundscape, reinforcing the subjective perspective of the diary while resisting conventional emotional inflection. This auditory “realism,” however, stands in stark contrast to the film’s anti-picturesque visual style, where Bresson’s minimalist framing abstracts both space and action; dialogue becomes reading, not speech; voice becomes temporally untethered, recounting events it no longer inhabits. The body is alienated from the text, and the text from the body; the line, whether scratched, spoken, or inscribed, persists beyond its material source, following only its own logic of graphic abstraction.

The liquidity of Diary’s medium—its very specificity—manifests as a cinematic force, fusing the diary’s lines with space and the priest’s deteriorating body. On one hand, writing instruments—ink and pen—parallel the ritual of drinking: wine warmed on the stove, dry bread dipped into the cup, mirroring the pen’s descent into ink. On the other, a transmutation unfolds—ink becomes wine, wine becomes blood—yet, in a cinematic defiance akin to Godard’s dictum, “It is not blood, it is red,” the substance transcends its referent, refusing a fixed identity. Not ink, not wine, not blood, but a dark liquid that absorbs inscription itself, binding the act of writing to the space it inhabits. Here abstract lines precede both gesture and text, moving fluidly between spaces and materials.

The movement of lines in the space, following the moment the priest is framed against the AMBRICOURT sign, the film positions him within the confines of his parish—yet always behind lines. The composition holds him through the rigid metal bars of the gate, their vertical grid doubling the lines of the diary, at once inscription and enclosure, script and cell. These gridded lines dissolve into the landscape, where the barren winter trees extend the abstraction, their skeletal branches reiterating the diary’s restless marks, integrating a rural location and a minimalist visual language to achieve an “abstract realism” as Colin Burnet puts it, which operates paradoxically: it engages with reality but does so through an abstraction that resists conventional mimetic representation. The film allows these lines to unfold the narrative while simultaneously abstracting it, tracing an interplay between imposed structure and organic dispersion, between confinement and the gestures that evade it.

The lap dissolve in Diary of a Country Priest operates as a transitional force that not only mediates between shots but also extends the film’s material concerns—its liquidity, its textual and bodily inscriptions, its dissolution of stable spatial and temporal coordinates. As Metz suggests, the lap dissolve foregrounds “its textual progression, its mode of operation in the virtually pure state,” calling attention to its own process of transformation rather than simply serving narrative continuity. In Diary, this mechanism becomes a cinematic equivalent to the material transitions we discussed: the priest's ink dissolving into wine, wine into blood, space into its own abstraction.

Like Metz’s description of the dissolve as a moment of "travel" that "hesitates on the threshold of a textual bifurcation," Bresson's use of the dissolve aligns with his aesthetic of restraint, where the priest’s body, his diary, and his environment bleed into one another, yet resist full condensation. The liquid movements—wine poured, ink absorbed, bodily frailty consuming itself—find a formal corollary in Bresson’s dissolves, which do not simply transition between images but enact a material and conceptual transformation. As Metz writes, the dissolve is “a dying figure,” an image that “begins to take shape en route towards its progressive extinction.” This process mirrors the priest’s slow dissolution—his physical and spiritual unraveling—as well as the film’s overarching interrogation of inscription, erasure, and the instability of form.

A structuring principle in Bresson’s film, the lap dissolve functions much like the diary itself: just as the diary functions as both record and disappearance—writing as persistence and erasure—the lap dissolve embodies the paradox of presence and vanishing, movement and suspension, material endurance and its inevitable undoing. The priest’s world—Ambricourt’s gridded gates, skeletal trees, ink and wine stains fading into absence—is mapped through these cinematic gestures, where form is always in flux, unraveling and merging into its own residue. But the dissolve is not confined to transitions between shots; it extends to the graphic lines themselves, dissolving into and being overtaken by the cinematic.

In the final sequence, the lines fade alongside the priest’s health—dark ink softens into pale pencil, the marks weakening, emptied of force, mere remnants before death. Yet writing persists. Handwriting gives way to typewriting, its mechanical rhythm replacing the embodied trace, becoming more automatic, drained of expression. Just as Bresson’s models are stripped of intention and psychological inflection, the act of writing loses its interiority, reduced to pure repetition. No longer an imprint of thought, it becomes a monotonous line, an emptied gesture. This transition marks Bresson’s first true cinematograph—a shift from cinema to an austere inscription of movement and time, where Bernanos’s novel is no longer adapted as literature but rewritten through the camera’s inscription.

For Bresson, le cinématographe marks creation over mere direction, foregrounding being over seeing, models over actors, the pure image rather than theatrical gesture. Yet, beneath the surface of image and sound, lines persist—moving, trembling, folding—and not solely within the confines of Bresson’s le cinématographe, a term he rigorously defines as “a writing with images in movement and with sounds.” But abstraction in cinema does not begin and end with Bresson’s austere exactitude; it pulses elsewhere, inhabiting and disrupting other audiovisual textures.

Consider Akira Kurosawa: another painter-turned-filmmaker whose artistic origins parallel Bresson’s, yet whose cinematic strategies diverge dramatically—embracing theatricality, lens variations, and formal excesses. In Diary of a Country Priest, abstraction materializes through the delicately traced lines of blotting paper, tangled branches, scriptural handwritings, typewritten inscriptions, and the subtle, dissolving overlaps of one image into another. In Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), however, the lines migrate elsewhere, Kurosawa’s cinematic gestures—wipes displacing Bressonian dissolves, telephoto lenses supplanting the intimacy of the 50 mm—fold together another kind of visual abstraction, manifesting within the spectral architecture of the “Castle of Spider’s Web,” the labyrinthine Throne of Blood. Where Bresson’s abstraction materializes through inscription, Kurosawa reconfigures it through architecture—turning line from textural trace into structural breath.

Lines of the Spider Web

Following the chorus chanting in the style of Noh theatre and the sound of wind tearing across emptiness, Throne of Blood (1957) opens into void. A fog-thickened field, dense and opaque, where direction collapses, perspective dissolves, and orientation is stripped of coordinates. The screen is less landscape than surface, less depth than plane—an ungraspable opacity that conceals and flattens, awaiting incision. Through successive cuts and shifting angles, the film presses against this obscurity, edging closer, as if carving through the mist’s layered folds. Wind unsettles the fog, blowing it into dispersals, while the camera’s lateral movement excavates what the opacity conceals.

—The first thread stretches across the x axis, a filament laid into air.

After several lateral tracking movements, a monument emerges in its entirety: a horizontal glide along its axis reveals the support posts bracing it, bare sticks set like anchor points in a rough hub. Then, the camera shifts its gesture, moving vertically from top to bottom in a slow descent across the surface of the monument. This scanning movement releases the inscription, word by word: Kumonosu-jō, “Castle of Spider Webs”, closing the chant with the title of the film.

—A second thread descends along the y axis, weaving title into stone.

This is the image that will return in closure, doubled by ruin and reiterated by chorus, binding the film to its own end.

The chanting—

Look upon the ruins

Of the castle of delusion

Hunted only now by the spirits

Of those who perished

A scene of carnage

Born of consuming desire

Never changing

Now and throughout eternity

—merges with the final inscription: “Here stood the castle of Spider Web.” Opening and ending are sutured in this monument, a line of architecture that binds memory, desire, carnage, and ruin. Past and present, reality and delusion, visibility and disappearance are all drawn into its axis. The web begins here, with the column, with the name, with writing itself, already entwined with its own erasure.

Out of this void movement emerges, cautiously, incrementally: riders circling in mist, advancing and retreating without exit, each trajectory already foreclosed, as though the field were written in advance. Space thickens into structure; suspension itself becomes architecture. Every step, every gesture is caught within hesitation, delay, disorientation. The opening renders the world as web before any web is seen, thresholds drawn in air: line as atmosphere and architecture, the invisible lattice on which the visible will be hung.

This architecture of filament finds resonance in theoretical accounts that likewise invoke the spider web as a model of structure, tension, and delay. Both Timothy Corrigan and Gilles Deleuze turn to the figure of the web to conceptualize cinematic forms of capture. Corrigan invokes it to describe the spatial logic of filmic description, while Deleuze associates it with narrative deferral and the suspended rhythms of “breath-space.” In his essay “In Other Words: Film and the Spider Web of Description,” Corrigan opens with a passage from Adorno that frames description as a tensile system of interrelation:

Properly written texts are like spiders’ webs: tight, concentric, transparent, well-spun and firm. They draw into themselves all the creatures of the air. Metaphors flitting hastily through them become their nourishing prey. Subject matter comes winging towards them. The soundness of a conception can be judged by whether it causes one quotation to summon another. Where thought has opened up one cell of reality, it should, without violence by the subject, penetrate the next. It proves its relation to the object as soon as other objects crystallize around it. In the light that it casts on its chosen substance, others begin to glow.

Drawing from Adorno’s epigraph, in Corrigan’s essay the web becomes a figure for how interpretation gathers meaning belatedly—how viewers and critics, like flies drawn into its tensile strands, are suspended within a field of echoes, resonances, and refracted perceptions. Corrigan extends this metaphor throughout the essay to describe how cinematic images provoke rhetorical and affective responses that are never immediate but always entangled in memory, subjectivity, and form. The web models a structure of critical thought that is tensile yet porous, binding image and description, affect and articulation, in a dynamic interplay that resists closure. Description, then, according to Corrigan, generates as a suspended act of writing that both captures and is caught by the moving image.

In Cinema 1, Deleuze reads Throne of Blood through a logic in which space and narrative converge in the figure of the spider web—a configuration that structures perception through tension, delay, and suspended movement. Departing from Western narrative forms that progress from situation to action, Kurosawa begins instead with space: a field of forces shaped by mist, voids, and directional constraints, in which action hesitates before emerging. Deleuze names this spatial system “breath-space,” a topology that rhythmically expands and contracts, holding perception in a state of arrested potential. It is this breath-space that determines the film’s structure, preceding action, shaping vision, and bearing what Deleuze calls “the givens of the question”—elements embedded in the situation yet unread by the character. “The breath-space is transformed into a spider’s web,” Deleuze writes, “which entraps Macbeth because he has not understood the question, whose secret was held by the sorceress alone.” The web here is not simply a metaphor for fate; it is a spatial and perceptual field of misrecognition, in which the failure to extract the underlying question leads to premature and doomed action. Kurosawa formalizes this logic through his compositional strategies: the image suspends thought, threading movement through delay, building tension across a space already structured. Deleuze’s reading treats the web as a cinematic configuration rather than a symbolic overlay. Deleuze remains more concerned with thought than perception, as Jordan Schonig summarizes: with the “movement of the mind more than movement on the screen….” The entrapment of the character is thus inseparable from the film’s spatial logic: a misreading of the world formalized in the structure of the shot.

While both Corrigan and Deleuze turn to the spider web as a figure for thought—whether interpretive or cinematic—the logic of line in Throne of Blood also extends beyond metaphor into material and spatial practice. The film does not merely represent the web; it constructs it. Its architecture emerges through acts of drawing and building that align with what Marco Frascari describes as the facture of architectural thinking.

Marco Frascari, in “Lines as Architectural Thinking” redefines architectural drawing as a material act of making—facture—that simultaneously records and performs architectural work. A drawing “is something in its own right,” a crafted object whose marks carry meaning through their facture, what David Summers calls “inferences from facture.” Ink’s luminosity, graphite’s density, watercolor’s translucence, or tempera’s weight function as traces of decisions, operations, and hesitations sedimented in the act of making. The drawing’s signifying force arises from what Frascari calls “the liturgy of its making,” where lines index constructive events and decisions as they unfold. Every stroke is an action that enacts architectural thinking, a gesture that both imagines and rehearses construction. To understand drawings as factures is to relocate agency in their processual, tactile dimension—erasures, smudges, pentimenti—each mark registering a cognitive operation, a trial, a moment of hesitation. Architectural lines thus create what Frascari names a graphesis: a course of actions through which architects actualize the past and the future of architecture into representations, turning drawing itself into a site of labor, imagination, and thought.

Extending this into the cosmopoiesis of lines—their world-making capacity, Frascari discusses how architectural drawing becomes a generative operation that mediates between the idios kosmos of private vision or dream and the koinos kosmos of shared, inhabitable reality. Lines are speculative hinges, carrying out what he describes as “back-telling” (from building to drawing) and “foretelling” (from drawing to building), movements that fold architecture into a chiasm where past, present, and future converge. To draw is to render visible what in construction remains concealed: tension, orientation, correspondence, delay. Lines operate as joints that bind materials, measures, and cultures into inhabitable orders, tangible signs that demonstrate “the intangible that operates in the tangible of a construction.” Architectural drawing emerges as an ethics of world-construction: slow, sapient, and translational. Hesitation functions as method rather than failure, a way of binding time, technique, and use into a cosmopoietic practice that gives form to architecture as a shared grammar of space.

Building on Frascari’s account of drawing as cosmopoietic operation, we might turn to Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, which he himself described as an “experiment,” unlike his other films. The experiment lies in drawing lines through camera movement, in constructing a castle before Mount Fuji only to alternate between its monumental exterior and the controlled space of the studio, in staging thresholds between landscape and construction. Here line becomes both cinematic gesture and architectural joint, weaving the structures of Noh theatre and the voids of sumi-e painting into a spatial architecture that hovers between visibility and erasure.

In this experiment, Kurosawa transforms line into a mode of thought: the camera draws, measures, and folds space, turning each frame into an act of construction. The film’s architecture is neither scenic nor symbolic; it is procedural, emerging through the rhythm of gesture, wind, and fog. The shifting thresholds between mountain and set, landscape and studio, summon a space where cinematic vision becomes architectural facture. Each movement—of camera, mist, or body—records both an act and its hesitation, the visible and its imminent disappearance.

The film’s spatial logic draws deeply from the traditions that underwrite its world. The line of Noh theatre, traced in the actor’s path across the stage, inscribes motion within stillness—a geometry of passage that never resolves into destination. The line of sumi-e painting, by contrast, opens the image through erasure, allowing ink and emptiness to co-constitute form. Both traditions fold presence and absence into a single gesture, and Kurosawa’s experiment translates this aesthetic into cinematic architecture: lines that build through void, structures that breathe through suspension. I have explored these painterly and performative dimensions of line in greater detail elsewhere, where I trace how Kurosawa’s compositions, drawing on the principles of sumi-e and Noh, open a mode of vision that unfolds beyond cultural or historical enclosure.

In this “experiment”, cinema itself becomes a form of drawing—a medium of construction that thinks through hesitation, delay, and erasure. The line no longer outlines form; it generates it. It operates as a hinge between media and worlds, joining the tangible with the invisible, the architectural with the atmospheric. Across Corrigan’s web of interpretation, Deleuze’s breath-space of entrapment, and Frascari’s cosmopoiesis of construction, Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood reveals the line as abstraction in its most material sense: not a mark of representation, but a process of world-making.

—A geometry of tension, drawn in mist and ruin.

Yet line need not be always graphic, need not declare itself through visible design or dramatic motion. Line may also emerge as disjunction: a force of relation, a trace of deferral, a materialization of absence. What, then, of lines without marks—those perceived only through what they disturb, through their capacity to bring surfaces into tense adjacency, to expose fragmented networks and spatial voids? What does it mean to follow such a line in cinema—not to illustrate connection, but to trace its failure, its withheld juncture? What is divided when a line insists on distance, on difference?

Inflected Interiors

Tsai Ming-liang’s Days (2020) opens with (such) a line: a faint architectural reflection cleaving Kang’s (Lee Kang-sheng) forehead as he sits in an extended stillness that thickens into gesture, stretched beyond the bounds of intention—about six minutes of suspended gaze, of time compressed to the point of pressure. The frame becomes an assemblage of contradictions, caught between the storm outside and the calm within: a white wall, a white shirt, a neutral chair indistinguishable from flesh, an untouched glass of water—all stilled, all trembling beneath an offscreen assault. Meanwhile, within the same interior, yet rendered through reflection, shadows of trees—stirred by wind and rain—agitate the upper third of the frame, folding the exterior into the domestic. Sound displaces vision: rain is heard but withheld, its presence spectral. Below, the outline of his body dissolves, absorbed by the floor, by the frame. A sharp table corner intrudes from the bottom left like a vector, angling toward Kang and returning us to his face, bisected by a radiant diagonal—the line we started with, the refracted edge of an exterior wall. This line, this luminous incision, evades fixed delineation, exerting pressure that bends, folds, and gathers force. Space compresses around it, thick with perceptual strain—as if the image were pinched by two surfaces held just apart. Between them, a floating line emerges like a threshold: not drawn, not predetermined, but perceived—a zone of contact that holds proximity without fusion, presence without form. The cut arrives not from narrative cues but from bodily limit: by Tsai’s account Lee could no longer keep his eyes open. Fatigue dictated the edit, the eyelid’s heaviness echoing the wall’s diagonal, inscribing weariness into vision itself and marking the body as the surface where cinema’s line is registered.

Building on Irene V. Small’s account of the organic line as a structuring interstice—a “line of space” that unsettles boundaries without becoming contour—I read Days as a queer cinematic practice of restructuring: abstraction realized through adjacency without resolution. Thresholds, supports, reflections, and pressure-marks on skin operate as the film’s abstract machinery, materializing queer temporality and space at seams where surfaces hesitate to meet. The organic line also reminds us that cinematic lines themselves are provisional, always subject to disappearance: every contour in cinema, whether architectural, corporeal, or optical, is ephemeral, flickering in and out of legibility. In this sense, the organic line foregrounds the precariousness of cinematic form itself—a medium built from intervals, dissolves, and gaps—where relation is continuously made and unmade, held only as long as duration permits.

Days makes the organic line visible as cinematic structure: seams between materials (door/frame, pane/air), reflective overlays, and support imprints on skin act as hinges of adjacency, holding proximity without fusion. These interstices do concrete work—organizing duration (holds), posture (fatigue, slump, bracing), and spatial drift (rented rooms, corridors, thresholds)—so that queer form is generated across edges rather than within unified figures. In Sara Ahmed’s terms, bodies “take shape” along lines they follow and deviate from; Tsai films that deviation at the level of contact held in suspension. Muñoz’s horizon of queer futurity appears here as delay and near-miss: relation glimpsed in intervals, not secured in resolution. Schoonover and Galt’s account of queer cinematic time—flicker, anachronism, ellipsis—finds in Days a complementary tactic: saturation and stall, where surfaces thicken into membranes and time collects as pressure Abstraction, in this account, is topological: a choreography of seams, holds, and reflective planes that re-situates narrative cinema within art-historical debates on the line as structure.

Described in Small’s book The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, the term organic line was first applied by Lygia Clark in 1954 to describe the liminal fissure that appears when a collage element meets its passe-partout. “Initially manifesting as a graphic phenomenon internal to the work and its conventions of display,” the line was, as Small explains, ultimately “secured to an experiential realm beyond the work itself.” Clark identified neither a painted edge nor a linear trace, but a “line of space” produced through adjacency and friction—fragile, contingent, relational. Unlike the contour that fixes separation, this line sustains tension. It occupies the unstable zone between coherence and dispersal, operating less as boundary than as connective tissue: a site of binding, folding, leaking. “A fissure of space between material elements,” As a line of space between features— a fissure that is observed, rather than made —, Small writes “the organic line is ontologically distinct from these technical, artistic, and philosophical articulations.” It functions as a hinge: contact that never fuses, nearness that never resolves.

Small situates the organic line against multiple lineages. From the technical, exemplified by Rodchenko’s constructivist definition of line as “the path of passing through, movement, collision, edge, attachment, joining, sectioning.” From the artistic, in Paul Klee’s diagrammatic classification of lines into active, medial, and passive types—“I fell, I fall, I am being felled”—a schema that treats line as grammatical and procedural. From the philosophical, in Deleuze and Guattari’s “lines of flight,” which rupture systems through deterritorialization. Where those depend on direction and syntax, the organic line recedes and binds. As Small puts it, it is “the space between the tree and the ax, a nothingness that otherwise escapes legibility and invites metaphoric elaboration.” Crucially, this void becomes structure, allowing Small to reimagine modernist surface as a topology—flexible, deformed, porous to what exceeds it. The organic line articulates, in her words, a “paradigm of between rather than beyond,” one that unsettles inherited schemas of origin, influence, and linear development that undergird modernist thought.

The film traces two solitary lives—Kang, a middle-aged man in a spacious home, and Non, a young Laotian migrant in Bangkok—as their parallel routines unfold through extended, minimalist long takes. Their paths briefly converge in a moment of intimate contact during a massage session, followed by the exchange of a small music box and a shared meal. Their encounter, suspended across intervals and spatial recessions, presses bodies into asymmetrical proximity before each return to solitude, held within the ambient disorientation of space and time. From the first image, the film binds line, body, and space in a network of disjunctions—each site bearing the imprint of withheld convergence. As Nicholas de Villiers argues, Tsai reimagines queerness through spatial, temporal, and sexual disorientation, engaging with the local and diasporic specificities of characters displaced across Taiwan, Malaysia, and France. In Days, this appears as a lattice of rented rooms, alley gaps, thresholds, and hallways—a topology of touch marked by delay and the tension of proximity across difference—where the line organizes separation and renders relation legible as spacing.

In Chapter 3 of Inhabiting Networks, Subjecting Space, Small theorizes the organic line as a rupture within modernist architectural regimes—specifically, a challenge to the grid’s rationalized logic of standardization. While grids function as systems of capture and standardization—regulating space through modular repetition and representational control—the organic line emerges at their margins, as a “zone of integration and expediency;” as “a void between forms,” a seam or aperture that enables articulation without synthesis. In architectural terms, this line materializes in the “thickness of space that occurs alongside” structural units, such as “the seam between various materials” or the “line that separates a door and its casement.” Unlike the idealized continuity of Le Corbusier’s “stowage without gaps,” the organic line operates through disjunction, enabling parts to connect while preserving their difference, thereby redefining architectural space not as a container but as a contingent field of variation, “a mutually constitutive network in which the organic implicates subjectivity, materiality, and space in equal measure.”

With the body’s appearance in relation to the architectural line, the film extends what Deleuze calls a ‘cinema of the body,’ where the corporeal ceases to be subordinated to action and instead becomes the expressive medium of time itself. In Chapter 8 of Cinema 2, “Cinema, body and brain, thought,” Deleuze reconfigures the relationship between cinema, thought, and the body, and argues that it is through bodily exhaustion—through tiredness, waiting, despair—that thought is forced to emerge. Rather than positing the body as a mediating obstacle to thinking, Deleuze proposes a reversal: the body is the site where thought encounters its outside, where it becomes “the unthought”—life itself. He writes, “The body is never in the present, it contains the before and the after, tiredness and waiting. The daily attitude is what puts the before and after into the body, time into the body, the body revealer of the deadline”. Fatigue, hesitation, failed gestures—what Blanchot calls “the immense tiredness of the bod” in Deleuze’s term—become the time-image's privileged figures, displacing narrative causality with postural suspension. The cinematic body, then, is not representational but expressive, and time is inscribed in what Deleuze calls “attitudes or postures,” rather than in action, which “relate thought to time as to that outside which is infinitely further than the outside world.” In Small’s terms, this is the organic line’s temporal labor, a phenomenological dislocation of figure and ground that renders perception time-sensitive, embodied, and incomplete.

Tsai’s long take in the opening scene—as noted earlier, interrupted only when Lee Kang-sheng could no longer keep his eyes open—foregrounds the body as the ultimate limit of cinematic duration. The sequence does not resolve through narrative but halts at the body’s threshold, a temporal inscription etched in fatigue. This moment of exhaustion both structures the film and recalls a longer trajectory in Tsai’s practice, where Lee’s body has been the medium of duration, illness, and endurance. In Days, Kang lives with chronic neck pain, seeking and testing treatments across the film. Fatigue and strain register in his body across surfaces—through the visible wear of illness, the accumulation of tension, and the prosthetic devices that prop him upright.

Small’s notion of the void—an absence that occurs between surfaces—intersects with this cinematic body at precisely these sites of tension. The organic line materializes where structure wavers, where space and flesh misalign, where the body marks time without signifying it. Across Days, this disjunction crystallizes into a formal principle. Postures remain out of joint with the rooms they inhabit: Kang’s home refuses to enclose him; Non’s rented room offers no refuge. Touches—acupuncture needles, massage pressure, mechanical melodies—hover across skin without penetration, registering proximity without entry. What the organic line discloses is less symbolic meaning than spatial hesitation. It reveals the body as provisional, marked by fatigue, delay, and the inability of surfaces to hold. Contact falters, support structures press unevenly, and the film becomes a study in holding apart, in intervals where alignment collapses and abstraction begin.

Days thus renders the organic line both as formal logic and lived condition: a volatile seam that binds space and body through asymmetry, deferral, and unresolved proximity. Across its extended durations and architectural interstices, Tsai visualizes the temporal labor of the line—its capacity to hold separation, to register pressure without contact, and to inscribe duration where surfaces fail to meet. Here, abstraction is not subtraction or purification but topological operation: folded, adjacent, durational. Days marks a hinge in Tsai’s practice: a feature poised on the threshold of gallery, performance, and durational installation. It suggests a cinema attentive to thresholds, surfaces, and fatigue, edging toward the temporality of presence.

The implications reach even further. If the organic line names cinema’s seams, voids, and ephemeral edges, then Days suggests that cinema’s ontology has always been queer—already structured by hesitation, adjacency, and incompletion. Queerness here is not simply thematic or representational but ontological: inscribed in the very lines of the medium, in the way images lean toward disappearance, contact remains deferred, and relations never cohere. What Tsai makes visible is not only a queer temporality, but the ground condition of queer cinema: an art shaped by intervals and dissolves, where abstraction becomes the very form of relation.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2006.

Bernanos, Georges. The Diary of a Country Priest. Introduction by Remy Rougeau. Originally published 1936. New York: Macmillan, 1974.

Chion, Michel. Words on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press, 2017.

Conley, Tom. Cartographic Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Deleuze, Gilles. The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Translated by Tom Conley. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

de Villiers, Nicholas. Cruisy, Sleepy, Melancholy: Sexual Disorientation in the Films of Tsai Ming-liang. United States: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Frascari, Marco. “Lines as Architectural Thinking.” Architectural Theory Review 14, no. 3 (2009): 200-212.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. 10th anniversary ed. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Schonig, Jordan. The Shape of Motion: Cinema and the Aesthetics of Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Small, Irene. The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism. United States: Zone Books, 2024.

Notes

- Tom Conley, Cartographic Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, 2.

- Conley. Cartographic Cinema, 21.

- Conley. Cartographic Cinema, 5.

- Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, translated by Tom Conley, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press, 1993.

- Michel Chion, Words on screen. Columbia University Press, 2017. P.119

- Georges Bernanos, The Diary of a Country Priest, intro. Remy Rougeau (New York: Macmillan, 1974; orig. pub. 1936), 6.

- Bernanos, Diary of a Country Priest, 5.

- Bernanos, Diary of a Country Priest, 9.

- Conley, Cartographic Cinema, 137.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, trans. Minneapolis: Univeristy of Minnesota Press, 1989.

- Jordan Schonig, The Shape of Motion: Cinema and the Aesthetics of Movement. United States: Oxford University Press, 2022. Ch. 2 P. 43

- André Bazin, “Le Journal d’un curé de campagne and the Stylistics of Robert Bresson.” What is cinema 1 (1967): 125-143.

- Colin Burnett, The Invention of Robert Bresson: The Auteur and His Market. Indiana University Press, 2016.

- Christian Metz, The imaginary signifier: Psychoanalysis and the cinema. Indiana University Press, 1981. P. 276

- Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematograph. Translated by Jonathan Griffin. New York: NYRB Books. P. 7

- The literal translation of the Japanese title of the film, Throne of Blood.

- Theodor. W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, 87

- Timothy Corrigan, “In Other Words: Film and the Spider Web of Description,” in Kyle Stevens (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Film, Oxford Academic. 2022.

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement Image. United Kingdom: Continuum, 2001, 190.

- Jordan Schonig, The Shape of Motion: Cinema and the Aesthetics of Movement. United States: Oxford University Press, 2022, 97.

- Marco Frascari, “Lines as Architectural Thinking,” Architectural Theory Review 14, no. 3 (2009): 200-212.

- Marco Frascari, “Lines as Architectural Thinking.”

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism. United States: Zone Books, 2024.

- Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. United Kingdom: Duke University Press, 2006.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 10th ed. United States: New York University Press, 2009.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 9.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 9.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 15.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 15.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 10.

- Nicholas de Villiers, Cruisy, Sleepy, Melancholy: Sexual Disorientation in the Films of Tsai Ming-liang. United States: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 248-294.

- Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, 156- 188.

- Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, 189-190.

- Irene Small, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, 241-324.

Cite this Essay

Asadollahi, Sara Ghazi. Opening Lines.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 41, 2026, doi:10.20415/rhiz/041.e01