Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 41 (2026)

What is Data Art?

Natasha Lushetich

University of Dundee

Abstract: Data art is usually seen as an art form that uses data as material in the same way that sculpting uses stone or clay. This article suggests a different view. Data are never simply “raw material.” Consequently, the expression is better suited to forms of practical critique that problematize data ontologies through a focus on primary data, metadata, and data transposition. By experientializing these areas, the artistic practices under discussion – those of Ọnụọha, Elahi, Fujihata, Miebach and Dewey-Hagborg – shed light on complex data processes, the imbrication of archiving and anarchiving, quantity and quality, materiality and immateriality, and, most importantly, on data’s relation to knowledge.

Introduction

In the third decade of the 21st century, it is clear that the “raw material” view of data, which separates data operations into collection, organization, and “synthesis into finished knowledge” (Silver and Silver, 1989: 6), is strikingly similar to the colonial view of terra nullius. It has the same effect of nullifying existents and ignoring their complex interrelations in order to justify interest-driven projections and, in many cases, outright misappropriation. The oversimplified data-information-knowledge – or DIK – hierarchy (NI, 2013: 4) additionally suffers from the same shortcomings that many visualizations of complex phenomena do. It grossly oversimplifies these phenomena, separating them from epistemic and technical processes to facilitate their de-contextualization (Hall and Dávila, 2022). As Dan McQuillan has noted, data science’s derivation of actionable conclusions from opaque algorithmic processes has neoplatonic tendencies in that it treats these processes as revelatory of a hidden mathematical order that is superior to human knowledge and experience (McQuillan 2018). But this is not a theoretical problem alone. In the public domain, the supposed “given-ness” of data is justified with pro-democratic narratives about transparency and accountability. Relentless data harvesting on, for instance, urban mobility and fuel consumption is seen as revelatory of patterns that will make “social processes more efficient” (Turner, 2006: 25; Kelly, 2016: 1). What a “more efficient social process” is is anybody’s guess; the only “efficient” process here is technocratic solutionism (Morozov 2014).

Clearly, data are neither “raw material,” nor are they just given, as “the world as database” view would suggest (Manovich 1999). Rather, a process more akin to weaponization is needed to turn what is (mistakenly) seen as “evidence” of phenomena – rather than phenomena in their own right – into knowledge. It is also closely related to a form of Artificial Intelligence that is best described as milintelligence. Essentially a target machine rooted in the military-industrial complex and widely used in business, milintelligence is concerned with understanding the enemy’s – or competitor’s – movements and translating them into strategic advantage (Lushetich, 2022: 121–122) Such an approach is nowhere more evident than in critical practices that use detournement – the practice of diversion, reversal and subversion of signifying processes pioneered by the Situationists International with the aim of re-purposing to make milintelligent weaponization visible, such as Paolo Cirio’s.

Known for works like the 2014 Street Ghosts, in which life-size printouts of accidental passers-by captured, without permission, by Google for Google Maps were displayed in the exact same physical locations, Cirio’s 2020 work – straightforwardly called Capture – is a collection of French police officers’ faces. For this work, Cirio harvested thousands of public images of the police during the 2018 – 2020 protests in France. He subsequently processed them with the Facial Recognition software, created an online platform and a database, crowd-sourced the police officers’ identification by name, printed their headshots as street posters and pasted them on buildings across Paris. Wedding the supposed given-ness of data – it’s all there for the taking – to the problematic of machinic and algorithmic appropriation, Capture is perhaps the best illustration of Cathy O’Neil’s by now classic equation of opaque algorithmic procedures with “weapons of math destruction,” laid out in the eponymous book (O’Neil 2016).

Already in 1997 Nicholas Negroponte had warned that an “increasing number of atoms” were being “turned into bites” and transported to the virtual world, where they could be easily manipulated (Negroponte, 1997: 13–18). In order to combat such tendencies STS and sociology developed, in the 2010s, the concept of data assemblage. Indebted to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theorization of “complexes of lines” that build a “territoriality” (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004: 587), data assemblages [agencement] are “technological, political, social and economic apparatuses […] that frame the generation and deployment of data” (Kitchin and Lauriault, 2014: 1). They are shaped by infrastructures, institutions, modes of governance and individual human actors and entwined with datafication, a process that transforms social actions into quantified data (Van Dijck, 2014: 198).

What is striking about data assemblages is not so much the entanglement of a much wider variety of elements and networks than the DIK logic acknowledges; it is its relation to agency. If we translate the French agencement more directly, as “agencying,” a different form of agency – as forces arising from a particular arrangement , sequential, material or virtual (Bennett, 2010) – begins to emerge. In what follows, I discuss the critical practices of Mimi Ọnụọha, Hasan Elahi, Masaki Fujihata, Nathalie Miebach and Heather Dewey-Hagborg to, firstly, articulate data’s agencying through a focus on: 1) primary data, which includes collection and archiving; 2) metadata – the data about primary data; and 3) transposition, the use of data for purposes other than what they were initially collected for (Floridi, 2005: 354). Secondly, I argue against the “data as evidence of phenomena” and “gadgets as non-agentic tools” paradigm to show that non-reductively understood data processes have profound implications for the production of contextually integrated, rather than correlational or causal knowledge that the DIK paradigm has popularized (Han, 2017: 63).

Primary Data: Archives and Anarchives

Known for work such as the 2016 Pulse, a site-specific performance in which she connected herself to a heart monitor and broadcast a visualization of her heartbeat in real time, Ọnụọha’s 2016 – present Library of Missing Datasets, which consists of the initial 2016 work, the 2018 0.2 and the 2022 0.3 iterations – is a physical repository of “data” that have been “excluded in a society where so much is collected” (Ọnụọha 2022). “The word ‘missing’ is inherently normative; it implies both a lack and an ought” (Ibid).

Clearly, nothing is a datum by itself; rather a datum is that which “exhibits the anomaly,” often because it is “perceptually more conspicuous” than the “background conditions” (Floridi, 2005: 356–357). However, a datum is also a datum because it is embedded in a system that recognizes it as a datum, be that system technical, socio-cultural or scientific. An alphabet with five missing letters is still an alphabet just like the missing letters are still signs. Ọnụọha’s missing datasets include police brutality, institutional racism, sexual assault, hate crimes against trans people, and the locations of Muslim communities surveilled by the FBI/CIA (Ọnụọha 2022). Echoing John Cage’s well known 4’33,’’ which thematized the culturally “blind” perception of silence, rooted in the hierarchical separation of music from ambient sound, Ọnụọha’s work foregrounds two operations: the cultural invisibilization of the “background” which upholds the dominant transparency paradigm, and the fundamental non-objectivity of datasets that is at odds with the supposedly eternal horizon of collection and archival a-priority.

Cage used three tacet movements (movements that indicate the partition an instrument is not required to play) to sensitize the audience to the sound of “silence,” not as a poetic conjecture alone, but as a palpable connection with the time-space in which the piece’s “non-performance” unfolds. Similarly, Ọnụọha’s Library of Missing Data Sets, like her 2017The Future is Here!, reveals the extent to which the contemporary datascape relies on vast amounts of humanly assembled and labelled data. Datasets are entangled with particular time-spaces as well as with the perceptual apparata that produced them. Even the iris set – arguably the most famous dataset used in machine learning – is, as Adrian McKenzie and Anna Munster have shown, a trace of particular perception events (2021: 67–68) . At some point in the late 1920s a botanist by the name of Edgar Anderson “knelt in the field amongst a colony of flowers, cut them, identified them by their species […], and measured the sepals and petals with a ruler” (68). The ensuing three-dimensional model isolated this experience, “sliced it along particular lines” and “inscribed it in the Iris dataset in a compressed form” (Ibid).

Although this may, at first, look like a problem of subjective human experience –often seen as rectifiable by machinic objectivism, – a quick glance at machine vision will show that particular classification is present in machinic perception, too, where “vision” refers to edge detection parameters, contrast ratios, the conversion of pixels to numerical values, and image trajectories across different scales.Since its inception, documentary (or evidentiary) art has called into question the supposedly evidentiary status of media (Berger and Santone 2016) challenging the “broader symbolic order” by “disturbing its totality” (Foster, 2004: 21). However, the “negative data space” that Ọnụọha reveals is neither a methodological critique nor does it refer to an one-off absence that can be rectified with a more visible approach to archiving. Rather, it speaks to archiving as such.

Archives – analog or digital – are violent technologies of inscription. They force coherence on incoherence with their rigid memory templates that order events chronologically, alphabetically, per geographical region, group, or nation. They suppress one type of information at the expense of another forcing visibility on latency. In recent years, there has been significant effort to decolonize memory institutions through the inclusion of marginalized populations and participatory archiving. Although these efforts are both praise-worthy and necessary they also affirm the dominant paradigm: visibility is good. More information is always better than less information. Lurking in the background of the visibiity paradigm is the a-priority of the archive, seen not as a record of life, but as that which determines what qualifies and should be classified as life.

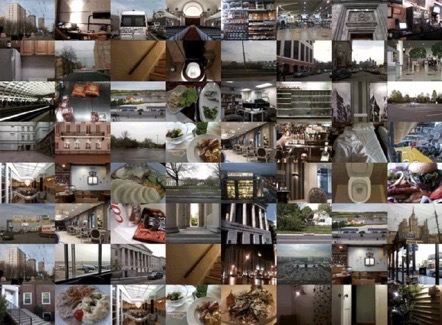

Moreover, the archive’s drive to visibility invisibilizes its anarchival underside.This is nowhere more evident than in Hasan Elahi’s 2002 – present day work Tracking Transience. Initially based on an erroneous call to law enforcement authorities after 9/11 that subjected the artist to a long investigation by the FBI, this project brings the visibilization drive to bear on the infinite, yet by no means linear, horizon of archiving. Although Elahi was cleared of suspicions after several months of interrogation, in an overbidding move – which is a move that raises the stakes higher than the system can respond (Baudrillard 2003) – he exposed, quite literally, all aspects of his life to view. Predating the NSA’s PRISM surveillance program by almost a decade, the project questioned the consequences of continuously generating data through self-tracking and uploading an endless stream of images of transportation logs, visits to restaurants, and toilets.

Since the last decade of the 20th century “anarchiving” has included all varieties of digital mnemonics. As Adami and Ferrini suggest, the term oscillates between “destruction,” “subversion,” regeneration and “un-explored potentiality” (Adami and Ferrini, 2014: para 3). In Elahi’s case, both the site of archiving (the internet) and the method (continuous uploading of images in real time) amplify the internet’s anarchival tendencies as, on the internet, data are contantly reorganized in micro-temporal executions of programmed code. This makes both the logic of archiving and meaning-making opaque. Already in the 1990s artivist groups such as The Yes Men used circumstantiality – the incapacity to discern the relevant from the irrelevant – to create a productive confusion between inside and outside, intended and accidental. In the last 15 years, the Dirty New Media movement has used computing to disorder proprietary software production through databending and obfuscation, an example of which is Helen Nissenbaum and Daniel Howe and Vincent Toubiana’s browser extension TrackMeNot, which sends randomly generated search queries to search engines and in this way obfuscating user information from corporate policies by overwhelming search engines with a wealth of data (Nissenbaum and Howe, 2015).

Elahi’s work takes this process further by creating an (an)archive in motion that turns data into digital dynamics and the archive into a “function of the transfer process” (Ernst, 2013: 98). Data here become signaletic material as it is difficult to grasp what we are looking at until we focus on a single image of, say, food and perceptually locate other, similar, images, then repeat the same procedure for other motiefs. For Deleuze, signaletic material includes all variety of modulations, “sensory, kinetic, intensive, affective [and] rhythmic,” that point to the excess of representation’s function, usually called noise (Deleuze, 1989: 29). In Tracking Transience, signaletic material shapes the communicative potential of the images – that could also be called data streams – highlighting the archive’s radically presentist temporality as well as its anarchival tendency to overflow, obfuscate, and disorganize. Like Ọnụọha, Elahi thematizes the enmeshment of primary data with socio-cultural and media-specific processes. Despite the fact that the DIK paradigm differentiates between unstructured and structured data, it ignores the agentic imbrication of perception (human or machinic) and data’s phenomenality. And this, as we shall see from the following section, is the fulcrum of Fujihata’s work.

Metadata: Quantity is Quality

The popular misunderstanding of metadata as quanticized data about data is based on the idea that primary data are evidentiary entities, and as such fundamentally additive. When related to specific locales and timeframes, metadata yield correlational knowledge, which serves the purpose of prediction. For example, credit card companies can make predictions about whether or not a couple is likely to separate years before they start talking about separation, based on the correlation of the times, locales, and frequency of individual credit card use (Harman, 2015). Although it is clear how this logic may serve business purposes, it is less clear how data can be primarily additive, particularly as additivity is repetition without qualitative difference. And yet, information – the reason why data are collected in the first place – is, in Bateson’s elegant definition, a “difference that makes a difference” (Bateson, 1972: 582). If framed as an entity, through linguistic performativity the data that contain the “difference” are themselves invariant. However if understood as a phenomenon and a process, the “difference” cannot not be present at more granular levels, too.

In the ancient Chinese mathematical work Jiuzhang Suanshu (Nine Chapters on the Art of Calculation), widely used throughout Asia, field measurements, volumes of shapes and solids, and the ratios of unknown dimensions, all bring scale, frequency, and velocity to bear on the structure of physical and social reality ( Schwartz n.d.). In other words: quantity is not separate from quality. Extensive quantities, such as length, height, and volume do not belong to a different category from intensive qualities, like pressure or density, except at certain thresholds, at 0 or 100 degrees Celsius where a quantity, such as a gallon of water, turns into a different quality: ice or vapour.

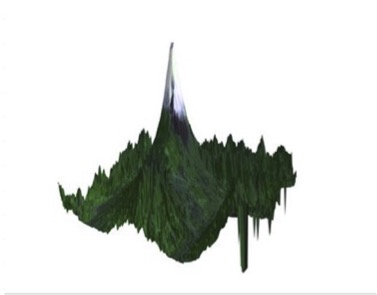

For several decades, Masaki Fujihata’s work has been concerned with precisely this: the qualitative life of data and metadata. In his 1994 Impressing Velocity, he climbed Mt. Fuji with his assistants carrying (what was then) a bulky and cumbersome GPS and a video camera to record the time, distance, altitude, and their constantly changing relationship to the climbers’ body (Kusahara, 2017: 65). The diagrams, maps, and computer-generated images obtained from the data showed the virtual shape of Mt. Fuji as a sculptural object proprioceptively experienced in the process of climbing. As even a brief description shows, the project was a prescient investigation into geolocation and the shifting relationality of all coordinates, recording, and transmission devices.

As Wolfgang Ernst has argued, over the past few decades, geospatial memory has changed drastically; “tools,” which are themselves “senders,” now produce geospatial information in “the geographic” and electromagnetic fields weaving “time” and “space” into a “spatio-temporal data tissue” (Ernst, 2018: np). Recorded sound, movement and their velocities form data tissue where quantity and quality are medially entangled. The highly problematic dualism of agent and patient, which stems from the history of Western metaphysics, denies things agency, attributing it, instead, to programmers or designers. Contra this view, Vismann suggests that a device’s features cannot be independent of its material properties and conditions. Using the expression “auto-praxis” (Eigenpraxis) (Vismann, 2013: 84), she insists that they steer medial processes in, for humans, unpredictable directions, processing data in specific, rather than generic ways, including the signal-noise spectrum.

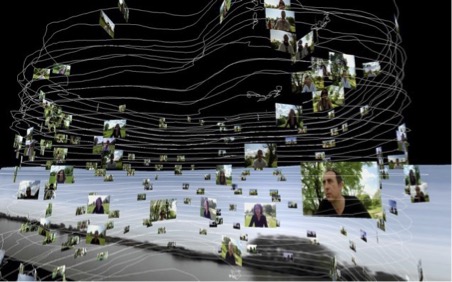

In his 2012 Voices of Aliveness, part of the 2002–2014 series Field Works, Fujihata collected spatial and temporal data from various human activities in a natural environment, tracing the participants’ movement and sound through a GPS system. Having created a path at La Martiniere in France, he invited participants to ride a bicycle along the path vocalising the process in the form of humming, singing or shouting. The bicycles were equipped with a GPS recorder and a video camera and as participants rode the bicycle, their movement was transformed into the shape of a ring. The collected shapes were then compiled into a tower-like time tunnel of collected sonic data. That is, the obtained metadata (location, duration and frequency) were turned into 3D images and location sounds, and presented as an interactive installation with a stereoscopic projection.

As with Impressing Velocity, the collected material was digitally converted into an abstract spatial map, to show the intensity of an ephemeral assemblage of bicycles, people, sound, movement and wind. In a composition of disjointed planes, the stereoscopic projection became a diagram of animated space-time as the audio-visual recording of each trajectory was combined with the geolocative data and the recordings of the various (non-identical) camera movements. Each screen, supported by a pyramid-shaped structure, both demarcated a minuscule field of projection, and acted as a magnetic compass enabling a display of the many points of view from which the audio-visual footage was recorded. The shifting angles and the perpetual movement of all coordinates delineated the infinite enfoldment of ontologically different (human and machine) and individually different (belonging to particular humans and machines) points of view (Deleuze, 1992: 82–83).

By collapsing the difference between data and metadata, and amplifying the working of geolocative and recording devices, as well as of space-time as such, Fujihata shows that all data are “thick” data: related to internally variant, rather than purely correlational knowledge – the knowledge that tells us that A is in some way related to B but doesn’t tell us why or how that is the case. The expression “thick data” (Boellstorff 2013) has been increasingly used – and misused – in recent years to denote a supposed difference from “thin” data. However, a datum can be seen as “thin” only within a conceptually discriminating structure that classifies it as such because it, say, doesn’t yield the desired volume or variety of information.

In reality, data thickness is similar to the thick description in anthropology, where the expression stands both for the describer’s recognition of data’s irreducible contextuality and their ability to describe it as such. This doesn’t refer to human beings alone; rather it includes the perceptual structures of devices and systems. Metadata is a useful expression to denote a different-degree data but should not be equated with smooth scalability of the kind present in the Charles and Ray Eames’ 1977 film Powers of Ten (Eames 1977) where the movement between exponential scales (10, 100, 10.000, etc.) is presented as smooth and continuous ignoring that data, like information, are, at different scales, subject to scalar disjunction.This further means that non-qualitative quantifiability is the effect of an arbitrarily selected, abstract and hegemonic “position of all positions,” (Bratton 2018) which ignores data’s complex interrelations. That said, the illusion of additivity and smooth scalability does render data future-ready thus serving the purpose of their operationalibility and futurability. And this, as we shall see from Nathalie Miebach and Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s work, is a side effect of data’s agentic malleability.

Transposition: The Immaterial is Material

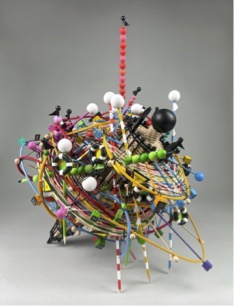

Miebach’s work is rooted in the transposition of numerical values and scientific measurements. Relying on sonification, sound notation, and physical – touch-inviting – materials, it articulates complex meteorological, ecological and oceanographic systems. Miebach’s main method, basket weaving, functions, in her own words, as a “tactile grid through which to interpret data into 3D space” (Miebach nd). The ensuing data interventions are epistemic in orientation and knowledge producing in effect. In addition to investigating historical metereological data, they investigate their underlying epistemic and measuring conventions adopting what Michel Foucault has identified as a pre-Enlightenment model of knowledge, that includes both scientific categories and personal points of view, in a move similar to Fujihata’s multi-perspectival installations (Foucault 1994).

Visually, Miebach’s sculptures are woven in such a way that “the visual chaos of colours” (Miebach 2023) hides little tags with “mph” or “Celsius” that anchor the forms in numerical logic. For example, her 2017 Harvey’s Twitter SOS transposed data maps of Hurricane Harvey published by The New York Times. The inner quilt was made of shapes that mapped income distribution in Houston alongside the city’s highway system, which was used as a visual geographical anchor. Other information, including Twitter messages that had been sent during the storm, was stitched onto the quilt, creating a labyrinth of repetitions and connections. More recently Miebach has used Covid-19 data alongside climate information in such works as the 2020 Spinning Towards a New Normal that transposed Covid-19 infection, death, and vaccination rates for several European countries into the form of a spinning top with a plumb bob.

Unlike smooth and aesthetically uniform data visualizations, that provide the overview first and details on demand (Schneiderman 1992), Miebach’s sensorial sculptures point to data’s infinite malleability. For example, her maps often double as musical scores that are further used for musical performances thus highlighting data’s genealogical imbrications. Epistemological imbrications are articulated through the use of standard systems for mapping wind levels, barometric pressure, and cloud cover alongside synaesthetic methods à la Kandinsky that rely on musical, pictorial and physical movement (Kandinsky 1946). This approach further sheds light on two things.

First, a system of relativity based on what Deleuze has called “in-com-possibility” (Deleuze, 1989: 130). Derived from Leibniz’s notion of “compossibility” as the existence of a plurality of worlds composed of radically different, even contradictory phenomena that are nonetheless “compossible,” Deleuze uses “in-com-possibility” to foreground that although configurations may not be literally compossible in the same world, they are relatively bound in the same universe (Ibid.). That is, they are not limited to perceptual systems with a common temporal denominator (for example, humans see glass as solid because the temporal frame within which window glass starts yielding to gravity, or travelling downwards, is 400 years). Many artists and collectives, such as Troika, have queried the relation of data modelling to scientific postulates and procedures. However, Miebach’s practice goes beyond questioning to show data’s energetic-agentic potential. With a long history in feminist critical theory, from Luce Irigaray’s 1970s concept of agency based on fluids (1985), Donna Haraway’s 1980s non-manifest ways of being that cross the human, animal and machine divide (1991), N. Katherine Hayles’ 1990s informational patterns (1999) and Karen Barad’s 2000s agential realism where agents emerge from intra-actions with phenomena and apparata (2007), agentic compounds show very different cycles of relationality. This relationality cannot be squeezed into a linearly causal frame but nonetheless galvanizes the micro-configurations that govern multiple relations of causation.

By experientializing geneological transposition Miebach foregrounds a process very different from visualization – which is essentially compression – namely re-materialization. Re-materialization makes it tangibly clear how one small part of a system can reel off an entire sequence of events – characteristic of emerging agency that the famous the “butterfly effect” has emblazoned on the cultural imagery (Gleick 2008). The question that therefore looms large on the horizon of multi-agentic possibilities is the question of futurability (Berardi 2017). Dewey-Hagborg’s work sheds light on precisely this: data’s latent and futurable agencies. In her 2013 Stranger Visions, she created human masks from the DNA obtained from found objects such as chewing gum and cigarette butts.

Based on scientific work that predicts human faces from their DNA with the aid of a computer program FacePred, using an average face based on sex, genomic ancestry, and the person's DNA to overlay the changes in their facial features based on genotypes (Matheson 2016) as practised by scientists such as Shriver, the project enacts a problematic practice to make that practice visible. As Dewey-Hagborg explains, since “the gene commonly associated with blue eyes and Northern Europe, also appears in the DNA of Hispanic, African-American, and South Asian population, data determinism [which weds data to a single cause] should be understood as genetic determinism” (2017: np).

If her concern with the increasing use of the DNA mugshots by government agencies seems stretched, suffice it to look at the 2015 Hong Kong initiative Cleanup Challenge, in which a company called Parabon Nanolabs offered DNA Snapshot as a solution to public littering, promising an “accurate” report including eye, hair and skin color, “face morphology” and “detailed biogeographic ancestry” to enable infallible detection of street litterers (Parabon Nanolabs quoted in Ibid). In Stranger Visions, Dewey-Hagborg purposefully produces a wide variety of faces to show the (extremely poor) level of precision that such predictions are based on. Although companies like Parabon Nanolabs argue that, as with Google Translate, precision will increase with optimization, what is at stake here is a grossly oversimplified causal logic. This is even more problematic than the facile correlational logic as it leads directly to injustice and social harm.

Concluding Thoughts

Apart from articulating the entanglement of data collection, socio-cultural practices, technical systems, and data’s contextuality, malleability and futurability, the discussed practical critiques articulate three other dimensions. The first is obvious: reductive knowledge models based on correlation and causation enact epistemic violence, similar to the colonial variant, which disqualifies all other epistemic possibilities – traditions and angles – on the basis that they are unscientific and therefore irrelevant (Chakrabarty 1992). The second is related to operational velocity; it is noriceable, albeit often only retrospectively: the denial of other relations among data, such as multi-agentic reciprocal causation, the milintelligent DIK logic is incomparably faster. Like the economic logic, which arose from the corruption of the 19th century religious institutions yet retained the same organizing principle (the trinity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, translated into the trinity of production, reproduction and distribution of wealth), it subjects heterogeneity to a reductive logic concerned solely with its own smooth operation (Gorz 1989). Today, this logic is no longer Trinitarian. According to Ken MacKenzie Wark, it is “vectoralist;” which, coming from “vector,” designates the rapid linking, direction and (re) direction of informational flows in media ecologies (MacKenzie Wark 2019: 71–73).

The third is by far the most important: as practical forms of critique, Ọnụọha, Elahi, Fujihata, Miebach and Dewey-Hagborg’s work articulates alternative knowledge configurations that open onto in-com-possibilities. The common critique of dataism and the DIK hierarchy is that it cannot produce truly contextually integrated knowledge. For example, in his discussion of GWF Hegel’s notion of knowledge, where correlational knowledge (A is in some way related to B) is considered inferior to causal knowledge (A is the cause of B), which is considered inferior to reciprocal knowledge (A and B cause each other mutually), Byung-Chul Han suggests that dataistic knowledge-production precludes the most complex form of knowledge that “comprehends within itself A and B and their context” (Hegel quoted in Han, 2017: 68–69). Although I agree with Han that this type of knowledge is most relevant, I disagree that data processes cannot generate it. As the above practices show, data’s inseparability from prevalent socio-political dogmas and technical logics doesn’t mean that data are not phenomena. Nor does it mean that the knowledge they produce is not onto-epistemological, where coming into being – of materials, processes and beings –is entwined with knowing. Rather, the view of data as vectorializable bytes is not only an operation that enables extraction of unprecedented proportions; more importantly, it is stikingly at odds with our contemporary reality where multi-agentic compounds – from plastiglomerates to the wekinator – point to a future of increasing (in-)com-possibilities. As a simultaneously creative, theoretical and technical endeavour, data art renders transparent both the complexity of knowledge-production systems needed for such a future and the (very concrete) harms of the DIK paradigm.

References

Adami, E. and Ferrini, A. (2014) “Editorial—The Anarchival Impulse,” Mnemoscape 1, 2014: mnemoscape.org/single-post/2014/09/14/Editorial-–-The-Anarchival-Impulse.

Barad, K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Half-Way: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bateson, G. (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine Books.

Baudrillard, J. (2003) The Spirit of Terrorism, trans. Chris Turner. London: Verso.

Berardi, F. Bifo. (2017) Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility. London:Verso.

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Berger, C. and Santone, J. (2016) “Documentation as Art Practice in the 1960s,” Vis Resour 32(3–4), 201–209.

Boellstorff, T. (2013) “Making Big Data, in Theory,” First Monday, Vol.18, No.10, doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i10.4869.

Bratton, B. (2018) “Evening Lecture – ‘There Never was a Horizon…’”, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwprt9cZxrE.

Chakrabarty, D. (1992) “Postcoloniality and the Artifice of History: Who Speaks for “Indian” Pasts?”, Representations. No.37, Winter 1992, 1–26.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (2004) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London and New York: Continuum International Publishing.

Deleuze, G. (1989) Cinema 2, trans. H. Tomlinson and R. Galeta. London: The Athlone Press.

Deleuze, G (1992) The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

van Dijck, J. (2014) “Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data Between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology,” Surveillance & Society, 12(2), 197–208.

Dewy-Hagborg, H (2017) e-flux: conversations.e-flux.com/t/heather-dewey-hagborg-hacking-biopolitics/6045.

Eames C. and Eames R. (1977) Powers of Ten: youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0.

Ernst, W. (2013) Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ernst, W. (2018) “Tracing Tempor(e)alities,” Media Theory, Special Issue: Geospatial Memory, Vol.2, No.1, np. mediatheoryjournal.org/wolfgang-ernst-tracing-temporealities/.

Floridi, L. (2005) “Is Semantic Information Meaningful Data?” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. LXX, No.2, March 2005, 354: doi.org/10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x.

Foster, H. (2004) “An Archival Impulse,” October Vol. 110: 3–22.

Foucault, M. (1994) The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London and New York: Vintage Books.

Gorz, A. (1989) Critique of Economic Reason, trans. G. Handyside and C. Turner, London: Verso.

Hall, P.A. and Dávila, P. (2022) Critical Visualization: Rethinking the Representation of Data. London: Bloomsbury.

Haraway, D. (1991) “Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late 20th Century, “ Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, London and New York: Routledge, 149–181.

Hayles, N.K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harman, G. (2015) “What is an Object?,” Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 16 January 2015: youtube.com/watch?v=9eiv-rQw1lc.

Han, B-C. (2017) Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, trans. E. Butler. London: Verso.

Irigaray, L. (1985) That Sex which is Not One, trans. C. Porter and C. Burke. Ithace: Cornell University Press.

Kandinsky, W. (1946) On the Spiritual in Art, trans. H. Rebay. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Kelly, K. (2016) The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That will Shape our Future. New York: Viking.

Kitchin, R. and Lauriault, T. (2014) “Towards Critical Data Studies: Charting and Unpacking Data Assemblages and Their Work,” papers.ssrn.com, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?Abstract_id=2474112.

Kong, H-J. (2019) “Managing Unstructured Data in Healthcare System,” Healthcare Informatics Research, Vol.25, No.1.

Kusahara, M. (2017) “The Early Years of Fujihata’s Art,” Augmenting the World: MASAKI FUJIHATA and Hybrid Space-Time Art, ed. R. Kluszczynski. Gdańsk: LAZNIA Centre for Contemporary Art, 46–67.

Lushetich, N. and Campbell, I. (2021) (eds.) Distributed Perception: Resonances and Axiologies. London and New York: Routledge.

Lushetich, N. (2022) “On Ludic Servitude,” The Double Binds of Neoliberalism: Theory and Culture after 1968, eds. G Collett et al (Rowman and Littlefield, 2022), 103–121.

Lushetich, N. (2022) “Stupidity: Human and Artificial,” Media Theory, Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 113–126: journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/view/166.

Lushetich, N. (2022) “The Given and the Made: Thinking Transversal Plasticity with Duchamp, Brecht, and Troika,” in Lushetich, N. et al (2022) Contingency and Plasticity in Everyday Technologies. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 143–161.

MacKenzie Wark, K. (2019) Capital is Dead: Is this Something Worse? London: Verso.

Manovich, L. (1999) “Database as a Symbolic Form”, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Vol.5, Issue 2:: journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/135485659900500206.

Matheson, S. (2016) “DNA Phenotyping: Snapshot of a Criminal, Cell, No. 166: cell.com/cell/pdf/S0092-8674(16)31067-4.pdf.

McQuillan, D. (2018) “Data Science as Machinic Neoplatonism,” Philos. Technol. 31: 253–272.

Miebach, N. (2023) Stir World: stirworld.com/see-features-nathalie-miebach-turns-data-from-weather-systems-into-colourful-installations.

Morozov, E. (2014) To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs.

Negroponte, N. (1997) Being Digital. Coronet Books.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2013) US National Intelligence: An Overview: govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-PREX28-PURL-gpo126561/pdf/GOVPUB-PREX28-PURL-gpo126561.pdf.

O’Neil, C. (2016) Weapons of Math Destruction. New York: Broadway Books.

Rasanene, M. and J.Noyce, J. (2013) “The Raw is Cooked: Data in Intelligence Practice,” Science, Technology and Human Values 38: 5, 655–677.

Schneiderman, B. (1992) Designing the User Interface-Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Schwartz, D. (nd) “A Classic from China: The Nine Chapters,” The Right Angle, Vol.16, No.2, 8–12.

Silver G.A. and Silver M.L. (1989) Systems Analysis and Design. Reading MA: Addison Wesley.

Tsing, A. L. (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Turner, F. (2006) From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vismann, C. (2013) “Cultural Techniques and Sovereignty,” trans. I Iurascu, Theory, Culture & Society, Vol.30, No. 6, 83–93.

Notes

- First developed by the Frankfurt School in the 1930 to combat the reductionist effects of positivism, critical theory articulates normative aspects of instrumental rationality. Since the 1950s, practice-based critique has been increasingly used. Artivist critiaque has similar goals, and additionally appeals to experience and affective-sensorial judgment. Détournement is an example of a practice-based critique. See Knab, K. (2006) Situationist International Anthology. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, available at: monoskop.org/images/8/80/Knabb_Ken_ed_Situationist_International_Anthology_rev_exp_ed_2006.pdf

- See: mimionuoha.com/the-library-of-missing-datasets

- Cage’s 4’33’ replaces conventional musical notation with numbers and words. The word “tacet” is used to indicate the section during which an instrument is not required to play, directing the performer to remain silent during three movements and sensitizing the audience to ambient sound.

- For more elaborate discussion of machinic perception, see N. Lushetich and I. Campbell, “Introduction,” in Lushetich, N. and Campbell, I. (2021) (eds.) Distributed Perception: Resonances and Axiologies. London and New York: Routledge, 1–13.

- For more information, see N. Lushetich, “On Ludic Servitude,” The Double Binds of Neoliberalism: Theory and Culture after 1968, eds. G Collett et al (Rowman and Littlefield, 2022), 103–121, 109–110.

- See: www.trackmenot.io/

- See, for instance: H-J. Kong, “Managing Unstructured Data in Healthcare System,” Healthcare Informatics Research, January 2019, Vol.25, No.1, 1–2.

- Data are often linguistically delineated as entities which has a performative effect.

- See also Mary Beth Marder’s work on Deleuze’s notion of intensity: Marder. M.B. (2017) Philosophical and Scientific Intensity in the Thought of Gilles Deleuze, Seleuze and Guattari Studies 11 (2): 259–277.

- For more information on the effect of aut-praxis, see medial efficacy, see Lushetich, N. (2020) “Algorithms and Medial Efficacy,” Philosophical Salon: thephilosophicalsalon.com/algorithms-and-medial-efficacy/

- See Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, 6–9.

- On scalability, see Tsing, A.L. (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- In particular, see Troika’s work: troika.uk.com/

- Berardi uses “futurability” to suggest that even within the current crisis, there is a horizon of possibility.

- A piece of software that doesn’t have a specific set of functions but instead connects to dozens of coding tools and recombines their functions in new ways.

Cite this Essay

Lushetich, Natasha. “What is Data Art?.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 41, 2026, doi:10.20415/rhiz/041.e07