Place and the Electrate Situation

William Tilson and John Craig Freeman

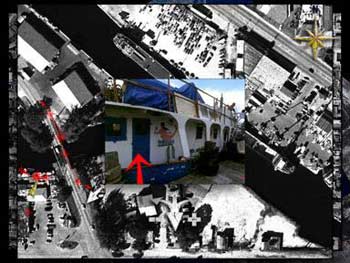

Composite image from "Imaging the Miami River", Place-Based Virtual Reality, Florida Research Ensemble, 2004.

"When I stay in one Place, I can hardly think at all; my body had to be on the move to set my mind going." —Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

"We wish to see ourselves translated into stones and plants; we want to take walks in ourselves when we stroll around these buildings and gardens." —Frederich Nietzsche.

"From a thousand different sites, the production of place continues to be possible."

—Ignacio de Solá-Morales.

Imaging Place

[1] The Florida Research Ensemble (FRE) [i] is working collectively and individually on the invention of new digital forms and the development of what Greg Ulmer, the group theorist, refers to as electracy. Electracy is to information technology what literacy is to alphabetic writing. Several projects have emerged out of the work that the group did on the Miami River including "Imaging Place," a place-based, virtual reality art project, which takes the form of a user navigated, interactive computer program that combines panoramic photography, digital video, and three-dimensional technologies to investigate and document situations where the forces of globalization are impacting the lives of people in local communities. The goal of the project is to develop the technologies, the methodology and the content for truly immersive and navigable narrative, based in real places.

[2] Although the method borrows freely from the traditions of documentary still photography and filmmaking, it departs from those traditions by using nonlinear narrative structures made possible by computer technologies and telecommunications networks. The work is projected up to nine by twelve feet in a darkened space with a pedestal and a mouse placed in the center of the installation enabling the audience to interact with it.

Installation view of "Imaging Place," 2006.

[3] Activated by the click of a mouse button, the interface leads the user from global satellite images to virtual reality scenes on the ground. Users can then navigate an immersive virtual space. Rather than the linear structure of traditional documentary cinema, "Imaging Place" allows stories to unfold through non-linear database navigation and multilayered spatial exploration. "Imaging Place" is therefore experienced as a process of navigation and excavation, allowing the user to uncover many layers of history and meaning. "Imaging Place" documents sites of cultural significance that for political, social, economic, or environmental reasons are contested, undergoing substantial changes, or are at risk of destruction. This includes historic sites as well as sites of living culture that are being displaced by globalization.

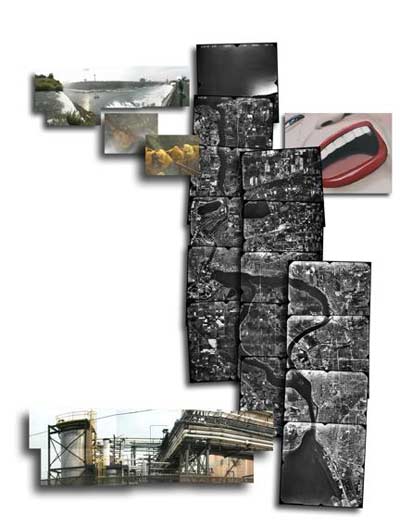

[4] The project also seeks to expand the notion of documentary by exploring how place is internalized, mapping place as a state of mind. We have come to refer to this practice as Choragraphy. Chora is the organizing space through which rhetoric relates living memory to artificial memory. It is the relation of region to place. Chora gathers multiple topics associated with a geographical region into a scene whose coherence is provided by an atmosphere. This atmosphere or mood is an emergent quality resulting in an unforeseeable way from the combination of topics interfering and interacting with one another. "Choramancy" is the practice of identifying and documenting Chora. [ii]

[5] "Imaging Place" is designed to accommodate interdisciplinary collaboration conducted across institutions and over distances. It uses new technology to bring disparate bodies of knowledge together in a single hybrid form. The method attempts to bridge the gaps in understanding that exist between esoteric disciplines that have developed as a result of academic and industrial specialization. The technological tools are now available for bringing the work of experts and stories of local denizens together without sacrificing the depth and dimension of specialized knowledge and to connect the abstraction of highly specialized thinking with the visceral experiences of people on the ground. In addition to providing a form for the generation, dissemination and accumulation of interdisciplinary research and artistic production, "Imaging Place" is designed as a model strategy for collaboration. It has its beginnings in a pilot project that emerged from a study of the Miami River in Miami, Florida.

Imaging the Miami River: Routes-Roots-Rhizomes

[6] According to popular legend, Miami is the first city in modern times to be founded by a woman and created with an image. Julia De Forest Sturtevant Tuttle had read William Bartram's account of his travels in Florida and seen articles extolling the edenic virtues of this remote extension of the United States. When she arrived in Miami from Ohio in 1891, she faced an assortment of denizens inhabiting the scene: a Seminole community, a few entrepreneurs, pirate-adventurers and ne'er-do-wells. Miami—a name derived from mayaimi which meant "big water" in the language of the Mayaimis, Calusas, and Tequestas tribes, offered unrelenting mosquitoes, no natural resources and little solid ground. In 1895, Tuttle sent an invitation to railroad king Henry Flagler in the form of a fresh orange blossom from her garden. The orange blossom, resting on moist cotton inside a small box, required no explanatory note. Flagler, who was shivering in the Great Freeze in Ormond Beach, could not resist the message of the gift. The instantaneous mental geography created by this meta-image of Florida enticed Flagler to extend his rail line to Miami by 1896.

[7] This anecdote is most probably apocryphal but instructive-the orange blossom acted as a rhizome that invented the city of Miami. What makes the Miami River ripe for our study is that since this encounter, it has only been conceived in terms of images that mask its problems. Consequently, the river is now practically unknowable to the general public except through representations supplied largely by the tourism and entertainment industry, the chamber of commerce and the news media. We, the public, are estranged from the problem site and have to construct opinions, images and means of production solely from this material. The FRE plan is to counter this impasse by constructing a wide scope information landscape using the internet. Imaging the Miami River employs testimonials constructed from direct contact with the river using mystory techniques. [iii] The Miami River project is no less deliberate in the editing of images, selection of messages and driving ideology than those employed by the commercial sector, but the difference is that their motives are hidden and FRE's paramount intent is to expose the limits of principle. [iv]

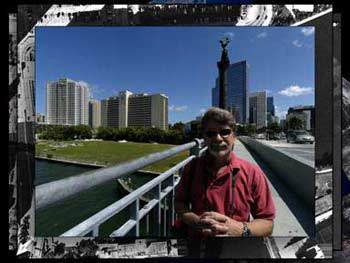

Navigational Interface with Greg Ulmer, still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," Florida Research Ensemble, 2004.

Aerial and satellite images the Florida Department of Transportation and NASA.

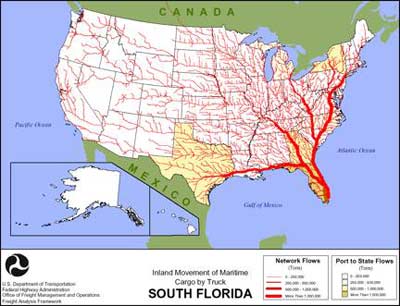

[8] Despite rapid gentrification since the project began, it still remains a place of work and, as Raymond Williams remarks: "a working country is hardly ever a landscape" (read: "conceived as an image"). The Port of the Miami River is the fifth largest in Florida and generates significant income for the state from water related industries.

Inland Movement of Maritime Cargo by Truck from South Florida, U.S. Department of Transportation.

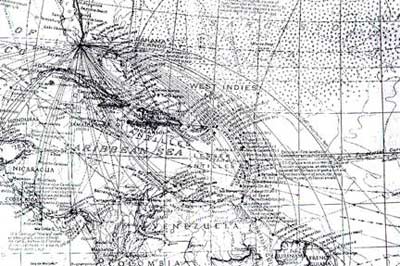

[9] The city of Miami is a quite literally a threshold between the US and Latin American and the Caribbean and the river is a hinge for this connection. Air and cruise ship traffic aside, the Miami River connects the city to over 72 ports of call throughout the hemisphere with most of the traffic operated by small shipping contractors in vessels of 100 tons or less.

Map of Caribbean Trade, William Tilson and Jeff Skoda-Smith, 1995.

[10] Overseeing this process are over 32 local, state and federal agencies-many with competing agendas—which are responsible for the regulation of the river zone. Through this bureaucratic entanglement, drift the denizens of the zone, immigrants, legal and otherwise, marginalized peoples, idiosyncratic personalities—rich and poor.

Agencies With Jurisdiction on the Miami River, U.S. Miami River Coordinating Committee.

[11] In spatial terms, The Miami River clearly exemplifies the dynamic and interdependent relationship between the smooth space of the sea and the striated space of the city grid explored by Deleuze and Guattari in 1000 Plateaus. [v] The conditions of the river zone demonstrate an urban space where there is a mixture or "holey space" that exists as constantly shifting degrees of interpenetrating social and physical realities. Everywhere there is leakage and contamination of one kind of space into the other. Like the Haitian boats listing at port along the river leaking bilge and taking on water, the unchecked pollution problems of the city seep into the river along its largely ignored watershed. [vi]

Impounded, still frame from "Imaging the Miami River."

[12] The diagonal cut of the river changes the complexion of Miami by creating obstructions in the rational order of the grid clearly shown in composite satellite images. From within the city, the only perceptible recognition of river life occurs in the rhythmic rise and fall of the drawbridges that interrupt the traffic flow of the street. At street level, the irregularity of the grid coupled with limited public access prevents a clear view of the river. These obstructions "frustrate our rational inclinations to identify a center, a base or a foundation" [vii] to the city's identity.

Crossroads, Haitian trading vessel on the Miami River, Barbara Jo Revelle, 1998.

The Impossible Walk

[13] "Crossroads" provided us with an image of the aporia and the first test of choragraphy. How would the method work in other disciplinary settings? What could we learn from Revelle's journey in rethinking the idea of placemaking in an electrate society? Tilson constructed a graduate seminar on the identity of public space, which used the Miami River as both context and subject. It was consciously built as an experiment in pedagogical hybridity. The subject matter, the mapping of psychogeographic space, falls in arena of the traditional seminar—the realm of rhetoric and discourse. The resultant body of work however, is located in the studio practice of construction.

[14] Although the seminar specifically avoided using hypertext and the Internet as the only medium, the seminar is an application of electracy applied to architectural discourse. As conducted, the seminar took on the appearance of one of its major methods: that of collage and of its site, the quilt-like spatial order of the Miami River. Tilson proposed to the seminar that they use Barbara Jo Revelle's river odyssey as a relay. [viii]

"So this was the poetic imaging method that Barbara Jo had in mind—done in terms of a divination structure—in the sense that when she toured the Miami River, she was looking for any clue or any cue, that would trigger an inner feeling. Something out on the river would trigger an inner feeling. And she was doing it specifically in the context of divination. As you know, the way divination works is that the querent has a problem, and when they go to the diviner and they consult the divination system, they have to pose what's called a burning question."

Barbara Jo Revelle interviews the captain of the Haitian trading vessel "God Is Able,"

still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," 1998.

[15] The "burning question" for the seminar was; "how can I be at home in Florida?" This question was framed succinctly in the winter 1993 issue of the Florida Endowment for the Humanities magazine with an image of a small picturesque cottage rendered in 19th century needlepoint style and bearing the title "Making Florida Home." Beneath the image of the cottage is the rhetorical question "Does this look like a Florida Home?" John Rothchild states in the opening essay that the identity of Miami results from a chaotic assembly of clans (exiles of varying nationalities, the elderly, young professionals and various and sundry denizens) in which the concept of home is not easily classified. At the spatial borders of these clans, is a condition of permanent stress that Rothchild labels a "geography of suspicion" that becomes an obstacle to the formation of a civic life. Nowhere is this geography more evident than in the Miami River zone. "Crossroads" images the aporia—a condition of being stuck in an intractable physical, psychological or intellectual situation that characterizes life on the river for its denizens. [ix]

[16] The seminar group wanted put the New Urbanist "5 minute walk" to the test. The concept of the five-minute walk is used as a ubiquitous measuring rod for urban health. The five-minute walk is presented as "A distance comfortable for most people to walk, as an attractive alternative to driving. This distance is best represented as one-quarter mile, 1,320 feet, or a five-minute walk." [x] The formulation of the five minute walk has many historical precedents as seen in the physical dimensions of the French Quartier in New Orleans and the Neighborhood Unit described in the 1929 New York City Regional Plan. Current urban initiatives such as Traditional Neighborhood Development (TND) and Transit Oriented Development (TOD) also use a five-minute walking distance as a primary design determinant. The basic tenements of New Urbanism state "Traditional urban patterns integrate human activities through a rich mixture of landscape and building, allowing the walk from one destination to another to be a pleasant alternative to driving." The Miami River, as well as other Imaging Place sites, defies this traditional definition of place. Research quickly revealed that taking this "pleasant alternative" was impossible due to the physically and socially discontinuous nature of the river's edge. In direct contrast to the nostalgic image of the city promoted by TND, making the "impossible walk" suspends judgment on the "health" of place by documenting it choragraphically.

[17] The impossible walk physically explored the historical, political, and artistic associations of walking in the city developed in such diverse practices employed by Walter Benjamin (One-Way Street) [xi], Andre Breton (Nadja) [xii], Kurt Schwitters (Merzbaus) [xiii], Sophie Calle (Suite Venitienne) [xiv], Richard Long (Walk Across England) [xv], and Richard Wentworth (To Walk) [xvi]. The impossible walk is also clearly aligned with the early psychogeographic walks framed by the Surrealist's "visits-excursions" of 1921 [xvii] and the Situationists "drifts" as in Ivan Chtcheglov's "Formulary for a new urbanism" (xviii) and Guy Debord's "Theory of the Derive." [xix] We were aware of the political and artistic limitations of the Situationists and the ironic emphasis they placed on the picturesque. There is an obvious alliance with Michel de Certeau's practices although we recognize that the nature of the city and pedestrian activity has changed along with predominate modes of representation and communication. [xx]

[18] Walking choragraphically maps the relationship of public, private and mental space in the Miami River zone. The class objective was to design cognitive maps that bridged the gap between our individual and collective imaginations and generated new narratives about urban space. We learned from Leonhard Euler and his study of the Königsberg Bridge problem (the Impossible Walk Theorem) that the simple, quotidian behaviors of popular or vernacular culture might become the source of theory. The Miami River Zone is crossed by thirteen bridges, where among other diversions, you can prove Euler's theorem for yourself. The premise is that events in the zone can be theorized and continually related to the development of new artistic, pedagogical, or political practices using the methods of the mystory. [xxi]

[19] Since the mystory asks users to integrate key images and figures from major institutions—family, community, the street, religion, entertainment, career, etc.,—we know the theoretical constructions will be non-linear and multivalent rather than monolithic and unified. In practice, our impossible walk functions to define place more like a Multi-user Object Oriented environment (MOO) than a Grand Unified Theory (GUT). The game from which a solution might emerge to the "Bridges of Miami" enigma must be something as much psychological as geographical—psychogeography. [xxii]

[20] The FRE groundwork-Revelle's tour, Freeman's VR nodes, allowed the seminar to get collectively "lost" in the river zone in the sense that Walter Benjamin uses the term. [xxiii] Being lost means gravitating toward attractions that indicate boundaries, rifts and seams within the zone that resonate in the memory of the viewer.

NW 17th Avenue Bridge at Sewell Park, Still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," 2004.

Traveling-Soloning

[21] The logistics of the impossible walk, while complicated, became part of the method. The University of Florida, known as the 'flagship university', is ironically grounded in an agrarian landscape a six-hour drive north of Miami. The class was divided into teams of four to accommodate the variety of schedules, fears and desires of visiting the river. Working in teams is common to architecture and planning but to question the function and internal relationships of the group, the teams were re-labeled as 'bands'. This label is borrowed from Ulmer's electronic writing courses, which emphasize a pedagogy collaborative writing (interestingly, Ulmer frequently refers to his writing classes as "studios"). The band simultaneously connotes a musical group (lack of cooperation produces discord) and a band of hunter-gatherers (the metaphorical basis of generating collage). Two members of the band were elected to actually visit the zone, while the other two remain behind working exclusively with representations produced through remote forms of communication such as instant messages, cell phones, and electronic postcards.

[22] The travelers took on the role of expert witnesses similar to that of the Greek theoros Solon, who traveled to distant lands and returned with first hand accounts of other cultures in the form of discourse, poems and souvenirs. The theoros declaimed his experience in public space in order that citizens might develop empathy with events and spectacles they themselves had not seen (FRE coined the term "soloning" or solonism to refer to this connection of mystory and travel). [xxiv] Unlike the example of Solon, our accounts involve the electronic apparatus to make them public.

[23] The members left behind act as interlocutors during the trip by asking for clarifications of intention through electronic communications—a kind of digital 'call and response' using email, cell phones and the MOO. We were inspired by the first transmission of African-American rhythms and into classical music by Frederick Delius, whose 1887 "Florida Suite", employed the reciprocal nature of call and response chants of African-American river men he heard while living on the St. John's River. [xxv] Using this example, we searched for other relevant collaborative analogues: the renga form of poetry that means "linked image" or "linked poem" and haibun, brief prose-and-poetry travelogues. These forms shift simple exchanges-cards, letters or conversations-into a poetics of collaboration that also direct contact with the denizens of the river. [xxvi]

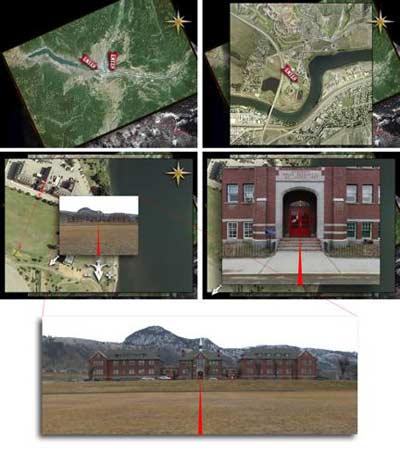

Miami River denizen Thomas Lopez, Still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," 2004.

"At the mouth of the Miami River. At the mouth of the Miami River. Second time I've been here in the last year or so. don't come down here very often. What I love the most about the river is the barges leaving for Haiti and the Bahamas ant the DR, just stacked with bicycles, 500, 700 bicycles, ranging from junkers to Cinellis and multiple thousands of dollar bicycles. Also the one that leave with mattresses, just stacked, they get redone apparently in the Dominican Republic and they get shipped back, not so much to the United States, but to other third world countries where they sell them for what's considered to be a fair amount of money, considering that they are getting them for nothing. They are just thrown away mattresses. So mattresses and bicycles, and I think that this is also one of the most interesting places for smuggling all kinds of things, illegal immigrants, illegal drugs, illegal everything. The Miami River is pretty interesting."

Rhythm of the walk

[24] We attempted to pick up the rhythm of the Caribbean found throughout the river zone and transpose this movement into the method of the impossible walk. The abstract walk was grounded in the scene of Kant's exercise. "In summer he walked very slowly, so as not to perspire; if he noticed that he was about to do so, he at once stopped, because he thought that his constitution required that he should by all means avoid perspiration. And it is stated as a remarkable fact that even in the hottest weather he never perspired" (Stuckenberg, 161). "In order to walk more firmly, he adopted a peculiar method of stepping: he carried his foot to the ground, not forward, and obliquely, but perpendicularly, and with a kind of stamp, so as to secure a larger basis, by setting down the entire sole at once" (De Quincy, in Cutrofello, p. 53, 1994).

[25] Rhetorically, the impossible walk teeter-totters between critique and objective practice: a distance that can be far apart or surprisingly close together. In practice, the impossible walk was often in limbo due to constant interruptions in the planned itinerary. The example of the limbo encourages flexibility in this context. As a religious term it is the place occupied by souls unable to be received in heaven or committed to hell (limbo-re: the plight of the Haitian boatmen). The dance by the same name, which originated in the Caribbean as a pastime for stevedore slaves, ironically enjoyed a brief popularity in the middle class youth culture of the United States during the 1960s: a period testing the limits of appropriate public behavior. Negotiating an increasingly narrow space under a bamboo pole is taken as a sign of the dancer's physical prowess and ability to overcome an obstacle. As the bar moves closer to the ground, only the most limber dancers can slip through the seemingly impossible space. The audience's call "how low can you go?" is responded to by the dancer's attempt to go lower. The "step" that enables a dancer to negotiate the low-point of the bar is a kind of "jump," thus imaging the digital or "catastrophic" (catastrophe theory plus poetry) properties of the "jumping universe" (Jencks, 1995).

[26] If the puzzle of continuous passage motivated topology—the example of Euler—, the puzzle of discontinuous passage does the same for choragraphy. Each break or discontinuity of the walk signaled the location of a potential relay. The impossible walk maps these breaks within the river zone and within us. The discontinuous, multileveled pattern that emerged is an image of the river's atmosphere experienced actually by the walk and made public by Freeman's VR constructions.

Baggage

[27] The actual walk taken by the travellers (which ultimately had to be assisted by car, bicycle and skateboard)-reveals the presence of innumerable socio-political and physical barriers, rifts, seams and voids mapped as different scales of containers. Coincidentally, most of the travelers were first or second generation immigrants, exiles and refugees. Their shared mystories revealed vivid memories of long trips in small vessels surrounded by people whose whole lives were contained in suitcases and cardboard boxes. These personal images of vessels within vessels containing innumerable secrets which, in part, explain the attraction of the group to containers.

[28] For example, the boxes of the bridge tenders hanging alongside the drawbridges offer a cognitive attraction. The periodic raising and lowering of the bridges that signal the ebb and flow of river traffic and the passage of vehicular traffic within the city are the only visible signs of the rivers existence in the skyline of the Miami. The tender's box is occupied twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week by workers—some of whom have spent their working lives alone within these containers. With their actions precisely timed with the flows of the city and the river, they are in a unique position to observe the occupation of the smooth and the striated.

Bridge tender booth at NW 7th Avenue, Still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," 2004.

[29] The travellers appropriated an American Tourister suitcase found during the walk to carry collected artifacts. The mystory technique employed in choragraphy makes this choice obvious. Discarded suitcases are ubiquitous in tourist-oriented Miami and are the storage vessels of choice among homeless denizens of the zone. Impounded Haitian boats are often piled high with luggage to be sold at other ports of call. The appropriation of the case binds us physically to the memory of the walk, and the philosophy of the method. The lexical field of the suitcase, which includes the valise, the steamer trunk, shipping containers, sacks, wallets, and portfolios, suggests many possibilities for making as shown in examples from Duchamp to Joseph Cornell.

[30] Suitcases can become symbolic objects among exiles and immigrants functioning as a "synecdoche for the unreachable lost home, and to act as a focus for memories of the exiles past life" (Warploe, K 92 in Morley Home territories p44). Similarly, the suitcase is often described as a "man's memory, locked or tied up with string" (Berger, Morley p44). Hannah Arendt is thought to have never unpacked her suitcases after escaping from the Nazis and settling down in New York City. Edward Said once remarked that like all Palestinians, he still over packs for a journey because of a "panic about not coming back" (Morley, p45). Back in Gainesville, the band used the suitcase to attune their personal question ("As an exile where is my home?") with an social problem ("What do we do with the homeless?").

[31] The Case of the Impossible Walk was designed for display in public space and serve as a model for an internet version. [xxvii] The images, anecdotes, archival references, and artifacts collected during the walk have been assembled into an interrelated set of components that include individual mappings of the walk, scenes of attraction and a series of 52 postcards. The frames that provide the physical and spatial structure for the contents are made of found materials-wood, metal and glass sheets-ubiquitous products in the river zone. The overall image of the assembly hovers between a precisely organized frame and overlapping surfaces clouded with images. The frame is never seen in its entirety nor is it completely obscured behind a screen of images. The various images found within the suitcase are made up of photographs, historical anecdotes, and theoretical quotations interwoven into a non-didactic construction after the principles of collage seen in Schwitters's and Cornell's oeuvre.

[32] The case reminds us that what we are designing is a tour or movement that connects "insides" and "outsides" (the Miami River in me, in the media, and in Florida). The possibilities of this mapping are explored in the frames within the suitcase which display layers of glass robbed of its pure transparency by acid etching, sandblasting and adhesive collage. The result creates an ambivalent reading of surface and depth much like Harry Callahan's images of Providence, made in 1967 that made the photographer and all lurking subjects explicit in the image. This phenomenon is informed by discussions with ecologists about the precise definition of the ground within the zone. Geologically we know that the river zone is a thin layer of moving soils floating over a porous, fluid bag. What seems solid at one moment may be liquid the next. All surfaces are moist and glistening. The earth may be an infill of dredge spoils or it may contain significant artifacts. Tequesta burial remains found during the excavation of Flagler's Royal Palm Hotel in 1896 were disposed of during the night to an undisclosed location (or given away as souvenirs). Cocaine bags, bottle tops, newspaper clippings, notes from immigrants to their families, and the like, are preserved with equality in our baggage.

[33] The technique of the mystory allows us to question the sources of artistic inspiration and forces an examination of preconceptions, assumptions and stereotypes in a precise way. The impossible walk is an unpacking of the mystory in real space-time. The activity of mapping the walk and structuring them into a container visualizes the monstrous appearance of the river. This de-monstration uses a process of constructing and construing as "an efficient means of thought." For example, a seagull feather placed in the box by a band member recalls the cautionary tale of Daedelus (the first architect, a thief and a convicted murderer) and his impetuous son Icarus. Along side the feather, perhaps not as formally elegant but certainly more poignant, is a piece of inner tube used by a refugee from Haiti who died attempting the ocean crossing. The case became a reliquary—or a monstrance—of the river which was used within the seminar to structure discourse on the identity of place. [xxviii]

[34] Using Freeman's interactive satellite mosaics, we can zoom out to witness the most visible allegory of the problems in us and the city: the highspeed Julia Tuttle Causeway that runs from the Miami International Airport to Miami Beach and crosses the river zone. On this route, and at the pace of the freeway, the gravitas of the city is erased from memory much like Tuttle's memory is erased and rewritten in the image of the orange blossom. Made at the pace of walking along the river, the Case of the Impossible Walk draws attention to choragraphy as a place making method in the contemporary city.

Imaging Niagara; The Daredevil

[35] Since this early work on the Miami River, the group has been testing the choragraphic method in various forms but immersion in the atmosphere of place through walking remains a fundamental strategy. The "Imaging Place" project now includes work from around the world including Sao Paulo Brazil, Kamloops BC Canada, Warsaw Poland, the U.S./Mexico Border, Boston, Kaliningrad Russia, Haverhill MA, Niagara, and Appalachia.

[36] In 1901, Annie Taylor, became the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. At age sixty-three, she was alone, broke and she was becoming too old to continue her work as a dance teacher. There was no social security at the start of the 20th Century so Taylor faced a future of destitution and poverty. The barrel stunt was designed with one of two possible outcomes in mind. Either she would survive the spectacular plunge over the cataract and be able to reap the financial benefits of fame, or she would end her life in an equally spectacular suicide.

[37] In "Imaging Niagara," a group of nine or ten year old intercity boys, jump from bridges on the Upper Niagara River for thrills. One of the boys named Skippy talks about his older brother jumping to his death from the Peace Bridge. Like the state of mind 'aporia' from the Miami River, 'The Daredevil' is the categorical image, which immerged from the attunement of the Niagara River Zone.

Composite image from "Imaging Niagara", Place-Based Virtual Reality, Florida Research Ensemble, 2000.

"What we are trying to do now in choral space on-line, digital memory is to have movement through a space be an act of reasoning by which a person could think about, and understand, and reason about problems and the world. We took a Situationist approach to this. The Situationist International was an avant-garde movement of anti-urbanism in the 1950s and 60s, very much part of what led to the famous May 68 rebellions in Europe, and in America too for that matter. But the Situationist applied poetry to life and they had a plan of moving through a city looking for its situations, as they said, or even to create situations. Their methodology is very important to the research Ensemble's methodology because they had this idea of drifting; they called it the derive, which was a kind of open passage, ignoring the normal traffic flows and circulations of the planed urban developments. And instead moving through a city in a way that followed its moods, that tried to track its emotions, the feeling and atmosphere of a place, to find what they called the plateau tourné, which are these turntables or hubs or vortices, which were these centers of power if you like, where forces came together to create strong atmosphere. So, for example when we talk about moving through, drifting through the zone, walking, whether that's a drift or a situation in a topological sense, moving through a space, something like the aboriginal dreamtime is a very good model for what we are trying to do; to find a digital equivalent. We can learn from how the aborigines mapped fully their cosmology and their mythology on to the landscape in which they lived. And as nomads they would do their walkabout or they would do their tours of their space, and their memory system was that as they came to each of their sacred spots the wise man or woman would tell the tales, tell the stories that were queued or trigger by the landscape in that particular place. And so, as they moved through the seasons, moved through their space, there was a kind of cognitive map, or an allegory, or a mystory, a collective story in which the culture, the civilization and the landscape that the people moved through were one in the same." Gregory Ulmer Gregory Ulmer on psychogeography, excerpt from "Imaging Haverhill: The Broken Bridge" 2003.

Imaging Sao Paulo

[38] The "Imaging Sao Paulo" project focuses on a small historic building in the city's center known as the "Castelinho da rua Apa (the Little Castle of Apa Street.)" In 1937, the castelinho was the site of a gruesome multiple murder and suicide. The details of what happened the night of May 12th that year remain unclear, as everyone involved died. The story survives as a kind of mysterious urban legend.

Panoramic still with Artur Matuck and Egle Spinelli from "Imaging Sao Paulo."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[39] The story goes something like this: Elza Lengfelder, the cook of the wealthy European family who owned the place, heard shots in the interior of the castelinho. She ran to the streets to call the police. When they arrived, the policeman found three bodies. They were the brothers Alvaro and Armando Reis, and their mother, Maria Candida Guimaraes Dos Reis. Dubbed "o crime do castelinho da rua Apa," the incident gained instant notoriety in the Sao Paulo press. It was assumed that Alvaro, a 43-year-old lawyer, threatened his brother with his 9mm German Mauser pistol during a dispute over a risky business deal involving a plan to start a casino. When the mother tried to intervene both the mother and brother were shot and Alvaro then turned the gun on himself. This explanation never quite fit the facts in the case and rumors circulated for over 70 years.

[40] After the crime, the castelinho fell into disrepair and became something of a squatter's shelter and crack house. Today the castelinho is being resurrected by the "Clube de Maes do Brasil (Club of Mothers of Brazil)." Founded by Maria Eulina. Without any support from the government, the organization helps the area's large homeless population acquire work skills, and feeds and educates the neighborhood children.

Panoramic still with the children of Clube de Maes do Brasil from "Imaging Sao Paulo."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[41] In "Imaging Sao Paulo: Castelinho da rua Apa," the audience is led thru the virtual space by Sao Paulo denizens and project collaborators Artur Matuck and Egle Spinelli, from the social drama unfolding in the streets thru the wreckage of the castelinho.

[42] Blindfolded, Matuck conducts a performative tribute to the city's homeless children in both English and Portuguese. The performance is based on newspaper articles where homeless children were photographed blindfolded to protect their identities. The blindfold becomes a metaphor for how the society has closed its eyes to the plight of these children. Spinelli helps Matuck—who has no eyes—thru the danger of streets and helps the virtual 'other'—who has no body—to navigate the scene.

[43] As the audience makes their way from the noise and chaos of the city streets into the relative quite, yet disturbing interior of the castelinho, the project takes a rather dark and deeply psychological turn as Matuck begins recalling an incident after the recent death of a close friend. He wanted to create a memorial performance where he would wear his late friend's pants. That night he had horrible dreams of the pants growing eyes in the tears around the knees. The next day he returned the pants to the family and said, "I cannot wear these pants." To which they replied "Of course, we didn't think you should."

Panoramic still with Artur Matuck, Christina Matuck and Egle Spinelli

at the Castelinho da rua Apa from "Imaging Sao Paulo." John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[44] The journey takes the audience from the very real political situation created by the mass migration of Brazil's rural peoples to the psychological subconscious represented by Matuck's account of his dreams and the graffiti on the walls of the "Castelinho da rua Apa."

[45] The project also addresses the Minhocao, a local nickname for the elevated roadway across from the Castelinho. Completed in 1972, the Minhocao roadway runs alternately as tunnels and viaducts as it winds through Sao Paulo, splitting the city and creating an abject space that attracts one of the largest homeless populations in the world. In the nineteenth century, many sightings surfaced from South America of a creature called the minhocao. An article by the French naturalist Auguste de Saint-Hilaire (1779-1853) in the American Journal of Science was the first published reference to this illusive creature of southern Brazil. Its name, he said was derived from the Portuguese word minhoca, meaning earthworm. Sainte-Hilaire recorded several instances, usually at fords of rivers, where livestock were captured by one of these creatures and dragged under the water. The minhocao is described as a giant burrowing worm-like animal up to 75 feet long, with black scaly skin and two horn-like tentacle structures protruding from its head, capable of digging enormous subterranean trenches. Although no credible accounts of sightings have been recorded since the late ninetieth century, the minhocao is commonly blamed for houses and roads collapsing into the earth.

Panoramic still beneath the Minhocao from "Imaging Sao Paulo."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School

[46] The "Imaging British Columbia" project includes work with the local Secwepemc (Shuswap) people that focuses on the stories of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Panoramic still with Don Seymour from "Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[47] The school was created in 1893 by the Canadian government in cooperation with Roman and Protestant churches to "Christianize and civilize" the Secwepemc. The school building, which stands today, was built in 1923 and operated as the Kamloops Indian Residential School until 1978. For most of its existence, little education took place at the school. Instead, the school was used to colonize and assimilate the Secwepemc.

Interface composite from "Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[48] Students were taught menial farming and homemaking skills, but most of their time was spent maintaining the school itself. Canadian law mandated attendance at the school and parents could be sent to prison if they refused.

[49] Over four generation of Secwepemc children were taken from their parents and forced to attend the School. These children were isolated from their traditional culture and indoctrinated in Catholic religious teachings. Although many of the children did not speak English, they were forbidden to speak Secwpemctsin and were severely punished when they did. The individuals I worked with referred to this practice as strapping, where the children would be hit across the forearms, or elsewhere, with large leather straps. The irony was, that the children themselves were forced to make the straps. The legacy of the Kamloops Indian Residential School has been devastating for the Secwepemc. Shame of the Secwepemc culture and language was deeply instilled in the children. The effects include all manner of personal, social, cultural, and spiritual dysfunction. The Secwpemctsin language was nearly lost.

[50] In "Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School," users can navigate through this imposing building where they will encounter several generations of former students recounting their experiences at the school.

[51] Since 1978 the Kamloops Indian Band has run the facility, which now houses a variety of Band organization. The word Kamloops is the English translation of the Secwepemc word Tk'emlups, meaning 'confluence,' and for centuries has been a center of the Secwepemc culture. Bands of first nation's people from across British Columbia are once again turning to the Secwepemc for leadership. They conduct a well-established project to preserve and restore the Secwpemctsin language and the school they run is one of the best in the state.

[52] At one time the Secwepemc people occupied one large traditional territory covering approximately 145,000 square kilometers. The Kamloops Reserve land base was established in 1862 under the direction of then Governor James Douglas. It included an area approximately 26 miles east of the North Thompson River by 26 miles north of the South Thompson River, adjacent to the City of Kamloops. Although the Secwepemc never signed away their rights to this land, in subsequent years the reserve was reduced in size to around 7 by 7 miles today. In 1988 the Kamloops Indian Band filed a claim to the original Douglas Reserve. In 2001 the Canadian Government rejected the claim. The Kamloops Indian Band is currently preparing to file a new claim under the Douglas Reserve Initiative at Residential School.

Panoramic still with Loretta Seymour from "Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[53] Future work on "Imaging British Columbia: Kamloops Indian Residential School" will attempt to map the stories of the Secwepemc people onto Douglas land claim.

Imaging the U.S./Mexico Border

Interface sequence from "Imaging The U.S./Mexico Border."

John Craig Freeman, 2006.

[54] In August 2005, Freeman traveled to U.S./Mexico Border region at Tijuana and San Ysidro to begin work on the "Imaging the U.S./Mexico Border" project.

"Increasingly, I am being drawn to those places where the forces of globalization are affecting the lives of local communities, places like borders and ports, walls and fences, the edges of public policy." —John Craig Freeman on borders fences and the edges of public policy.

Beginning on the western shore, where the fence terminates in the Pacific Ocean, Freeman plans to work his way east along border. There are three issues he is exploring with the "Imaging the U.S./Mexico Border" project. First is the contradictions and bigotry of U.S. Immigration policy toward Latin America. Second is the labor and environmental exploitations of North American Free Trade Agreement, and the third is global human trafficking, indentured labor, and the sex slave industry.

Full Circle

[55] In 1998, during the construction of a twin tower condominium complex called the "Brickell Pointe Towers" on the south bank of the mouth of the Miami River, a Tequesta Indian structure was unearthed. Originally scheduled for an opening celebration on the eve of the millennium, work on the project was immediately stopped due to the significance of the archeological find. [xxix] Unlike what happened in Flagler's day, the event did not go unnoticed. Using a digital camera overlooking the site, archeologists, preservationists and Indian Rights advocates broadcast images over the internet twenty four hours a day. Constant virtual scrutiny helped make the site a hot political topic. Development was halted and the city eventually purchased the property for the development of a riverside park.

Miami Circle, Still frame from "Imaging the Miami River," 2004.

[56] This project, although not created by FRE, is an early example of the power of electronic witnessing to affect public policy. Conventional wisdom in urban planning, particularly from the perspective of New Urbanism, asserts that good public discourse is dependent, at least in part, on good public space; and good public space is defined, at least in part, as a context conducive to good public discourse. Along the Miami River, the Castelinho da rua Apa, Kamloops, the Mexico-US border, and a thousand other similar sites, one learns to be a citizen, not by strolling amidst great monuments, and well defined public spaces (precisely because they do not exist in these zones), but through choragraphic activity of attunement. "Imaging Place" shows that public discourse in an electrate society emerges virtually. [xxx] A continuous trip cannot be made along the Miami River, whether by car or by foot Discourse on public policy issues in actual public space is therefore obstructed and dislocated.

[57] Planners prize continuity as a means to reinstate the Cicerian link between rhetoric and public space. "Strategy 5" of the Miami Master Plan, for example, seeks: "to physically unite and showcase the diverse districts of downtown with a continuous, active waterfront." The solution-the ubiquitous "riverwalk" presents the city as a panoramic scene. The proposed "Border Security Fence" between Mexico and the US is a clear image of the old adage "good fences make good neighbors." [xxxi] These two proposals disguise public policy problems with images that equate security -being at ease- with continuity.

[58] Choragraphy privileges interruption—the normative way of daily life. Warren Magnusson states that, "the city as the embodiment of urbanism as a way of life is not a merely local political entity. Nor can it be identified with the ancient polis, which is the model for the modern republic. No particular city is self-contained. Nor is there a singular order to the city. A city is multiple networked and diversely ordered, internally and externally." He goes on to say, "To be urbane or civilized is to take differences in stride, react with tolerance and curiosity to alien customs, and to see the diversity of the city as an advantage."

[59] The choragraphic method, which attunes the individual's sense of self to contemporary pop culture in an electrate age, allows us to be at ease with difference, obstructions and interruption. The process of attunement creates "virtual easements," where burning questions are publicly visualized via the Internet. Historically, easement is defined as a legal right or privilege of using something not one's own. In the modern city, a public easement is that space which is filled with connective infrastructure, e.g., water, sewers, telecommunication lines, but ironically prevents public assembly. In the "Imaging Place" project, the virtual easement is a space in which surveillance techniques (aerial image, web cams and eyewitness testimony) are used in the service of citizenship. This place of civic watching may turn to action in the realm of the virtual city.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible if it were not for the collaborative efforts of all the members of the Florida Research Ensemble. Gregory Ulmer provides the theoretical frame for the "Imaging Place" project and Barbara Jo Revelle's attunement of the Miami River has provided a model for subsequent work. This project was supported in part by a grant from the Emerson College Faculty Advancement Fund, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Small Cities Community-University Research Alliance, and the Museu de Art Contemporånea da Universidade de Sao Paulo. The Satellite and Aerial imagery was provided by NASA-GSFC, with data from NOAA GOES, GlobeXplorer, DigitalGlobe, and the City of Kamloops.

Works Cited

Allman, T. D. Miami: City of the Future, Grove/Atlantic, (1988).

Barthes, Roland, Richard Howard (Translator), Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, English translation, Staus and Giroux, Inc. (1981).

Benjamin, Walter, Berlin Childhood around 1900, (Translator) Eiland, Howard. Chtcheglov, Ivan, "Formulary for a New Urbanism," "Letter from Afar," "Preliminary Problems in Constructing a Situation," and "Theory of the Derive" (Editor-Translator) Ken Knabb, Situationist International Anthology, (1981, 2nd printing 1989, 3rd printing 1995).

Benjamin, Walter, (Editor) Roy Tiedemann, (Translator) Howard Eiland, and Kevin McLaughlin, The Arcades Project, Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA (2002).

Breton, André, (Translator) Richard Howard, Nadja, Grove Press Inc. New York, NY (1960).

De Certeau, Michel, "Walking in the City," The Practice of Everyday Life. (Translator) Steven Rendall, University of California Press. CA (1984).

Duany, Andrés, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Jeff Speck, Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream, North Point Press, New York (2000).

Long, Richard, A Walk Across England, Thames & Hudson, London, (1997).

Macel, Christine, Ive-Alan Bois, Yves-Alain Bois, Olivier Rolin, Sophie Calle: Did You See Me? Prestel Publishing New York, NY (2003).

Magnusson, Warren, "The City of God and the Global City," CTHEORY: Theory, Technology and Culture, vol. 29, no 3, (2006). «http://www.ctheory.net».

Malo, Álvaro, "Urban Landscapes: Intermodalities of Miami: Public Transportation Projects," Proc. of American Collegiate Schools of Architecture International Conference, 10th-14th June 2000. ACSA Press, 2000.

Morse, Margaret, An Ontology of Everyday Distraction, Logics of Television. Edited by Patricia Mellencamp. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, (1990), pp. 193-221.

Mitrasinovic, Miodrag, Total Landscape, Theme Parks, Public Space (Design Studies, Urban Studies, Architecture, Planning, Design and Built), Ashgate Pub Co, Hampshire UK, (2006).

Ulmer, Gregory L., Teletheory: Grammatology in the Age of Video, Routledge, 1989, 2nd Revised Ed., Atropos Press, New York/Hamburg, (2004).

Williams, William Carlos, Paterson, 5th Addition, New Directions, New York, (1995).

Notes

[i] The Florida Research Ensemble (FRE) is an interdisciplinary collaborative group working collectively and individually on the invention of new digital forms of research and the development of what Gregory Ulmer, the group theorist, refers to as electracy. Electracy is to networked digital media what literacy is to alphabetic writing. Over the past decade, the FRE has produced numerous exhibitions, books, articles, videos, lectures, panel discussions and websites. In addition to Gregory Ulmer, the collective includes architectural educator and urbanist William Tilson, digital media artist John Craig Freeman, photographer, videographer and performance artist Barbara Jo Revelle and net artist Will Pappenheimer.

[ii] The neologism choramancy (related to geomancy but claiming no universal or spiritual purpose) provides a critical method for an individual to attune themselves with place. Like geomancy, and other forms of divination, choramancy provides a structure for individuals to construct meaning from patterns of personal, institutional, critical and popular culture.

[iii] Ulmer first proposed the notion of the mystory in Teletheory: Grammatology in the Age of Video, but has continued to work with the idea throughout his body of work. Mystory is a puncept which alludes to history, mystery and feminist notions of herstory. It is structured around medieval allegory, which was designed to attune the individual's sense of self to the teaching of the Church. In this case however, the method is designed to attune the individual's sense of self to contemporary pop culture in an electrate age.

[iv] "We wanted to make an image that captures holistically the Miami River as a category. A picture of a Haitian trading vessel, loaded with goods, used mattresses, bicycles, plastic buckets, rice and other goods like, that was intended to go to Haiti, but the boat is impounded. It's been arrested, if you like, under the auspices of the Coast Guard, a particular Caribbean Safety Code. These Haitian boats particularly, but other boats around 100 gross tons, they were wooden, usually smaller kinds of vessels, and they didn't meet the standards set by the Coast Guard for safety on the high seas. So they were impounded, they were not allowed to leave the port, if they had already entered the port, until they had made certain kinds of improvements. Now, these boats were interesting because they were in a double bind. There would be something like $50,000 worth of improvements that needed to be made. But, in order for the boat owners to have that kind of money, they needed to leave the port with the goods that they had and go complete their business. They weren't allowed to leave the port until they had made the improvements. And they couldn't make the improvements until they had the money by leaving the port. So it was a double bind, a classic impasse. Essentially what happened was that the Haitian owner lost the boat. Because they were impounded on the river, they were paying docking fees, $100 a day. They couldn't pay the docking fees. The dock owners got the boat and the Haitians lost." —Gregory Ulmer on the categorical image, excerpt from "Imaging the Miami River" 2004.

[v] The observation that the Miami River was a perfect image of Deleuze and Guattari's smooth-striated space emerged from conversations between Alvaro Malo and Tilson. Malo, the former director of UF's Miami Architecture Education and Research Center, and his graduate students, developed a number of exemplary public infrastructure projects for the river following this assumption. Malo subsequently presented these ideas in a paper entitled "Urban Landscapes: Intermodalities of Miami: Public Transportation Projects," presented at the American Collegiate Schools of Architecture International Conference, in Hong Kong, 10th-14th June, 2000.

[vi] A partial list of problems identified by the Miami River Quality Action Team includes: under funded enforcement efforts, hazards to navigation posed by substandard vessels; improper rafting of vessels; bridge openings and obstructions; oil and hazardous spills; sewage discharges; illegal dumping; marine debris and solid waste crime; illegal immigrants; abandoned and/or derelict vessels; fire/explosive hazards and "hotwork" practices; transshipment of stolen merchandize/contraband/illegal aliens; riverside substandard vessels "on hold"; uncoordinated agency response to vessel arrival; and education of the general public. The public policy problem highlighted in the Imaging Miami Project was "substandard vessels on hold".

[vii] Earthwards: Robert Smithson and Art after Babel. Shapiro, Gary. P61. Although not described formally as choragraphy, Much of Smithson's work-particularly "A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey" published in Artforum, December 1967, explores the categories we ascribe to choragraphy.

[viii] Ulmer's definition of relay is being throughout this essay: "a term used to distinguish the use of an existing text or artwork to suggest a direction for further work, but that does not serve as a template or model that may simply be replicated in the new context. So for example the voudoun divination system, at work in Miami-Miautre, is a "relay" to help understand how to connect individual personal problems with a cultural archive of knowledge. But it may not simply be used as a blueprint for a contemporary wisdom practice (as happens in pop new age self-help behaviors).-the gaps are the locations to be bridged and connected."

[ix] Ulmer notes that: "We looked for some idea in our knowledge base of Post structuralism that coordinated with the impoundment of the Haitian boat, which had been shown to be the attunement of the zone. And of course, what we found—and it was a eureka experience in finding it—was Derrida's notion of aporia, which is a kind of absolute impasse. When you are thinking in terms of problems you are always thinking about solving the problem, but aporia sticks with the impossibility of the solution. Aporia is for problems, for which there is no solution—impasses such as the condition of the Miami River. It's not just the Haitians who are at impasse, but everything is at impasse there. That is, the best science, the best politics, the best that the modern American civilization can do, can't touch the problem of the Miami River." Gregory Ulmer on aporia, excerpt from "Imaging the Miami River" 2004.

[x] The core of the New Urbanism is in the design of neighborhoods, which can be defined by 13 elements, including "the five minute walk," These principles identify the characteristics of "authentic neighborhoods" according to town planners Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, two of the founders of the Congress for the New Urbanism. New Urbanism treats the contemporary city as a sick body that can be cured by implementing an idealized image of the city prior to WWII. This process involves the use of form based "Smart Codes" to achieve this end.

[xi] "One-Way Street" by Walter Benjamin does not belong to any existing literary genres like novels, poems or plays. It is made up of aphorisms, notes and observations, short essays, accounts of dreams and reflective descriptions.-perhaps a modern version of the grimoire?

[xii] Nadja by André Breton, originally published in France in 1928, is the first and perhaps the best Surrealist romance ever written, a book which defined that movement's attitude toward everyday life. Nadja is not so much a person as the way she makes people behave. She has been described as a state of mind. Our state of mind during the impossible walk equates to "atmosphere."

[xiii] Though Kurt Schwitters employed Dada ideas in his work, such as his Merz works—art pieces built up of found objects; some were very small, some took the form of large inhabitable constructions, or what would later in the 20th century be called installations. Schwitters's practice of collection materials during extended urban walks is presented as a method containing 12 categories of behavior outlined by Roger Cardinal in "The Cultures of Collecting" edited by John Elsner and Roger Cardinal. Reaktion Books, 1994.

[xiv] French photographer, installation artist and conceptual artist Sophie Calle's work is inspired by the use of arbitrary sets of constraints, much like the French literary movement from the 1960s called Oulipo. In "Suite Venitienne" (1979) Sophie Calle followed a handsome man she met at a party in Paris to Venice, where she disguised herself and followed him around photographing him. The series includes photos and her text of the pursuit.

[xv] Much of British conceptual artist Richard Long's works are based around walks that he has made, and often consist of photographs or maps of the landscape he has walked over. Starting at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, on the Devon coast, and finishing on the edge of the North Sea in East Anglia, Richard Long created a work of art out of an eleven-day walk across England.

[xvi] Wentworth's work was presented in an exhibition entitled "Walkways" funded by the Graham Foundation in 2002. The seminar was attracted to a quote by Claes Oldenburg in the catalogue introduction in which he argues for an art that "imitates the human" and "embroils itself with the everyday crap," P11.

[xvii] 17

(xviii) Ivan Chtcheglov's argued for "architecture of ambience," visualizing neighborhoods of luck, streets of tragedy, historical blocks, a city block of the dead, a neighborhood of misery, a scary alley, and so on. City blocks with positive or negative radiation would follow each other up so that every sense of urbanites would be activated, and they would be able to learn how they would want to live, think, feel and create. The city would become a center of discoveries and adventures—it would make life pleasurable, sexy, interesting and exciting. He wrote: "We are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun. Between the legs of the women walking by, the dadaists imagined a monkey wrench and the surrealists a crystal cup. That's lost. We know how to read every promise in faces—the latest stage of morphology. The poetry of the billboards lasted twenty years. We are bored in the city, we really have to strain to still discover mysteries on the sidewalk billboards, the latest state of humor and poetry."

[xix] "The derive, with its flow of acts, its gestures, its strolls, its encounters, was to the totality exactly what psychoanalysis, in the best sense, is to language. Let yourself go with the flow of words, says the psychoanalyst. He listens, until the moment when he rejects or modifies one could say detourns, a word, an expression or a definition." (Chtcheglov, "Letter from Afar").

[xx] While his idea of "map" or mapping carries the stigma of surveillance, Margaret Morse notes that, "De Certeau's vision of liberation via enunciative practices bears the marks of its conception in another time and place, that is, in a premall, prefreeway, and largely print-literate, pretelevisual world." She goes on to say that "de Certeau's very means of escape are now designed into the geometries of everyday life... Could de Certeau have imagined, as he wrote on walking as an evasive strategy of self-empowerment, that there would one day be videocassettes that demonstrate how to 'power' walk?"

[xxi] "What we try to establish is what the person's superego would be. Who are the four people from different parts of their experience, family, community, entertainment, career, that they most admired, and that would constitute their superego" Gregory Ulmer on mystory, excerpt from "Imaging the Miami River" 2004.

[xxii] We are using Guy Debord's most concise definition of Psychogeography: "The study of specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals" (Debord).

[xxiii] While examining the image of his own childhood to understand the relationship between physical and psychological space in Berlin Childhood around 1900, Benjamin remarked, "Not to find one's way in a city does not mean much. But to lose one's way in city, as one loses one's self in forest, requires some schooling" Benjamin, Walter, Berlin Childhood around 1900, (Translator) Eiland, Howard. Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA, p52, (2006).

[xxiv] For the discussion of the role of activity of Theoria and the role of the theoros, Ulmer relies on Placeways: A Theory of the Human Environment by E.V. Walters (1986). Walters relates this history to a discussion of good city form. Ironically, he does not formulate a modern equivalent of this process to counter what he sees as dissolution of place in an emerging global economy. A thorough examination of this tradition is found in Andrea Wilson Nightingale's Spectacles of Truth in Classical Greek Philosophy: Theoria in its Cultural Context (Cambridge University Press 2004).

[xxv] Florida for Delius was like Voyage of the Beagle for Darwin, or self-analysis for Freud, or the trip to Tahiti for Gauguin. As Delius later told Eric Fenby, his amanuensis: "I was demoralized when I left Bradford for Florida ...you have no idea of the state of my mind in those days. In Florida, through sitting and gazing at Nature, I gradually learnt the way in which I should eventually find myself, but it was not until years after I had settled at Grez that I really found myself. Nobody could help me. Contemplation, like composition, cannot be taught" (Fenby, p. 164-). Fenby, Eric. (1994). Delius as I knew him. Dover Publications, Inc: New York (republication of revised 1981 edition by Faber and Faber:London).

[xxvi] We were reminded of the use of these methods in more contemporary applications-those between Robert Rauschenberg and Alain Robbe-Grillet, Octavio Paz and Chris Taylor's renga walls. See Octavio Paz, Renga: A chain of Poems by Octavio Paz, Jacques Roubaud, Edoardo Sanguineti, Charles Tomlinson (New York: George Braziller, 1971), and Robert Rauschenberg Traces suspectes en surface. Text by Alain Robbe-Grillet. U.L.A.E./Universal Limited Art Editions. New York. 1980 (University of Texas at Austin copy reviewed). Also see Chris Taylor's experiments with renga and building practices at: http://arcworkerscombine.com/renga/. Taylor states that: "Renga is not a model of consensus around a single vision. Instead it provides a frame for the culture of a group to grow dynamically over time. Each participant works with finite resources to make a physical addition to the project. Responding to the particulars of its making, renga enables a reflective dialogue through radical action. Unified by time and material "RENGA: regeneration" is a model for creative and collective action in the environment."

[xxvii] This is not dissimilar to Diller and Scofidio's "Suit Case Studies: the Production of National Past," although the contents of the Impossible Walk Case do not have a fixed set of relationships.

[xxviii] Freeman's more recent Imaging Place projects, in effect, are true electrate reliquaries.

[xxix] Evidence of the circle's origins was reported in the article "Prehistoric Miami" by Mark Rose in Archaeology, Volume 52 Number 2, March/April 1999 . Rose notes "That the site remained undiscovered and survived nearly intact until now is miraculous. It was unharmed during construction of a three-story apartment building 50 years ago, when a septic tank was put through its center". This image reconfirms the problematic of the river zone.

[xxx] Virtual here is not the opposite of "real" but "actual." The invention of topology, for example, is directly connected to Euler's actual walks in Königsberg&8212;the invention of choragraphy is inextricable linked to the actual experience of Miami by FRE.

[xxxi] This adage derives from Robert Frost's poem "The Mending Wall" written in 1913. At the end of his life, Frost said it "illustrated the impossibility of drawing sharp lines and making exact distinctions between good and bad or between almost any two abstractions." Quoted in Robert Frost Himself by Stanley Burnshaw (N.Y.: Braziller, 1986), 289.