Exploring Border Country: the Use of Myth and Fairy Tale in Gillian Clarke's Poem Sequence, "The King of Britain's Daughter"

Diane Green

The female Welsh poet: sites of otherness

Even if one is not an actual immigrant or expatriate, it is still possible to think as one, to imagine and investigate in spite of barriers, and always to move away from the centralizing authorities towards the margins, where you see things that are usually lost on minds that have never travelled beyond the conventional and the comfortable. [1]

[1] Gillian Clarke is one of Wales' foremost poets writing in English at the present time. Her volumes of poetry have been released at intervals since the 1970s, the most recent, Making the Beds for the Dead, appearing in 2004. Her work has reached a wide audience, in part due to her lecturing and teaching activities, and has featured on school examination syllabi as well as on university courses. It is personal work, written out of a female consciousness, and sometimes considered "feminist"; her early "Letter from a Far Country," for example, was described as "a poem of the first political magnitude, as well as one of the great women's poems of any time". [2] Her introduction to that poem is a good indication of the background from which her poem sequence to be discussed in this essay—"The King of Britain's Daughter" from her collection The King of Britain's Daughter (1993) [3] —stems:

Letter from a Far Country is a letter from a fictitious woman to all men. The "far country" is childhood, womanhood, Wales, the beautiful country where the warriors, kings and presidents don't live, the private place where we all grow up. [4]

Whether writing personal recollections of family or a sheep on her small-holding, specially commissioned texts on particular places, or tackling political themes, such as the destruction of the Twin Towers in September 2001, [5] Clarke maintains a steady focus, seeing simultaneously through a woman's eyes, a Welsh sensibility.

[2] Critics of her early work have frequently paid attention to her brand of feminism, [6] whilst more recent critical work, including particularly her own perceptive analyses, has explored to some extent her role as a Welsh bard (one whose first language is English) and her later, more political, poetry. [7] M. Wynn Thomas has pointed to the androgynous stance, the ambiguous feminism, in "The King of Britain's Daughter" in particular; [8] however, in the light of the current emphasis within feminist studies on a lesbian approach and the popularity within literary studies of postcolonial work, it is appropriate at the present time to examine the many difficulties and ambiguities which occur in an exploration of Clarke's poetry as either feminist or postcolonial. This essay will approach such an exploration through a detailed examination of the use of myths and fairytales in "The King of Britain's Daughter."

[3] Her qualification for inclusion in "feminism's others" relates to this specific twin focus referred to above—the presentation of self as both feminist and Welsh [9] —a complex situation, which, whilst in conventional terms could be considered as doubling the poet's minority status (M. Wynn Thomas refers to the "twinned instances of oppression" in this context) [10] may indeed rather be seen as diluting it, due to her respectful and affectionate regard both for her father's influence and also for her Welsh heritage, [11] the frequently patriarchal traditions of her native land. Critics have already pointed to this effect: Thomas has described her instinct, when using myth, "to subsume gender difference within what, for her remains the overriding, primary, category of the undifferentiatedly 'human'". [12] Clarke's poetic voice remains firmly heterosexual and family-orientated, although the key sexual relationship in most of the texts she uses ultimately fails, and is unlikely to provoke discussion in the currently popular lesbian approaches to literature. Similarly, her Welshness is uneasily situated for inclusion in postcolonial discussions, although there is currently significant internal debate amongst critics of Welsh writing in English as to the feasibility and indeed accuracy of approaching Welsh writing as postcolonial; [13] this includes areas of debate on both historical and current issues: whether the nation of Wales is inextricably complicit in British imperialism, whether it can reasonably assert that its language and culture have suffered from aggressive English colonization, and whether it is indeed a marginal nation or an equal constituent element of those comprising Great Britain.

[4] Raymond Williams sums up, very succinctly, the view of the Welsh past as a history of "subordination": "To the extent that we are a people, we have been defeated, colonized, penetrated, incorporated". [14] In a later essay he outlines the process more fully:

English law and political administration were ruthlessly imposed, within an increasingly centralized "British" state. The Welsh language was made the object of systematic discrimination and, where necessary, repression. Succeeding phases of a dominant Welsh landowning class were successfully Anglicized and either physically or politically drawn away to the English centre. Anglicizing institutions, from the boroughs to the grammar schools, were successfully implanted. All these processes can properly be seen as forms of political and cultural colonization. [15]

Eventually generations of Welsh people came to believe that the best prospects for their children were likely to involve concentration upon English language and culture, and separation from the Welsh language that might also be in their backgrounds. John Prichard explained the situation in 1949:

Not only were we the first radio generation, but we were also the first generation, possibly in the world, to be denied our native language, not by statutory rule or government decree, but by the deliberate choice of our parents. All of us present have, or had, either one or two Welsh-speaking parents. Not one of us can speak Welsh. And the same is true of many thousands of Welshmen. [16]

The Welsh writers R. S. Thomas, Emyr Humphreys and Gillian Clarke were amongst those brought up in this situation, although, as will be seen in the poem-sequence under discussion in this essay, Clarke's father ensured her childhood was steeped in Welsh culture if not in the language, which she learnt as an adult. [17] David T. Lloyd, writing in 1994, claims that: "No matter what their relation to the Welsh language and its literature, all Welsh writers are affected by the tensions between the two literature and cultures. Speaking or writing Welsh communicates cultural—even political—allegiance, which partly accounts for the significant number of contemporary English-language writers who have learned, or are learning, the language." [18] Clarke's essay "Voice of the Tribe" articulates her own experience: [19] how English became her mother tongue at her mother's insistence, despite Welsh being the language of all previous generations in her family—"My father tongue was Welsh" (169). She outlines her understanding both of the tensions created in the Welsh writer because of the existence of the two languages—"English: the mother always sure she's right and knows what's best; Welsh, the father, luring to adventures beyond certainty, calling me to myself and to the greater world" (171)—and of the imperialist process of language imposition as a form of rape (169).

[5] It is certainly arguable, then, that Clarke might be discussed in postcolonial terms. At the present time, Wales is part governed by the Welsh Assembly and part by the British Parliament from London. In some eyes it is a region of Britain, in others a separate nation. Chris Williams' measured proposal that Wales be viewed not, using Michael Hechter's phrase, as an "internal colony" but as a "dependent periphery" allows for "inequalities between the two societies" (8), before concluding that "[a] 'post-national' Wales is a more attractive prospect" (16). [20] The political situation remains ambiguous; equally there are myriad possible cultural stances. More children are now educated in the Welsh language than were in the previous two generations. However, the majority of Welsh people is not bilingual, and their immersion in and awareness of Welsh culture runs the whole gamut of the possible range. Like the poetry of R.S. Thomas and the novels of Emyr Humphreys, Clarke's poetry is written in English, her first language, but is nevertheless redolent of a Welsh consciousness and produced in a Welsh landscape by a writer whose allegiance is to a small nation, often disregarded, deemed marginal. [21]

[6] Rather than use the term "marginal," however, it is perhaps useful to adopt Clarke's own insight into the meaning of "border," as outlined at the beginning of her article "The King of Britain's Daughter," [22] in which she explains the origins of her poem sequence in a 1990 workshop with other poets titled "Border: Fatherland, Motherland."

What I saw at once was the border country in the self where mother and father meet, an edge where there is both tension and conflict. At the same time it was the border where the two languages of Wales define themselves and each other, and the definition of self and other was one of the most intriguing aspects of the subject. The meaning of border deepened, layer by layer. I saw those borders inside Wales like a backwards journey into history where the post-industrial south dwindles among tin sheds and tethered alsatians, where sad ponies starve on the yellowed grass of slag, and where, one ridge onwards, another Wales begins as a mountain tilts westward into pasture and wooded valleys. Somewhere in this complex mental landscape of fractures and sutures a childhood tilts into adulthood.

Clarke's borders, her areas of conflict, are those formed in the child where the genes and the influence of mother and father counteract; they simultaneously occur in the cultural and geographical divisions within a society and in the uneasy transition between childhood and adulthood. Gloria Anzaldúa, in the seminal Borderlands: La Frontera (1987), defines her own borderland in similar, if more pronounced and more dramatic ways. [23] Anzaldúa describes a similar historical colonizing process, with the indigenous population forced to the edge of a country, happening to the Mexicans before the U.S. achieved the present border in the mid nineteenth-century, as happened to the Celts in Britain, driven to the western and northern extremities as Germanic peoples settled into the island. She outlines a similar, if more forceful, impetus for the individual's needs to be subsumed into those of the tribe to ensure its survival, as that discussed in Clarke's case above (40). The tribal culture, when rigidly patriarchal, is problematic for the rebellious female: "Culture (read male) professes to protect women. Actually it keeps women in rigidly defined roles" (39). However, Anzaldúa's borderlands are more extensive than Clarke's; they include race as well as nationality, but most significantly a lesbian identity: "Being lesbian and raised Catholic, indoctrinated as straight, I made the choice to be queer" (41). Through this "otherness" to the perceived norms of her own culture, Anzaldúa is herself able to become a symbol of the Anglo-Mexican border identity: [24] "The queer are the mirror reflecting the heterosexual tribe's fear: being different, being other and therefore lesser, therefore sub-human, in-human, non-human" (40). Her position highlights the problems faced by a feminist reading of Clarke's work. Her stance, in comparison with such as Anzaldúa's, may appear weakened, patriarchally complicit, murky where Anzaldúa's is clear. Nevertheless, it has validity and also importance; it argues the possibility of partial otherness: of being feminist whilst heterosexual, nationalist whilst using "the language of the oppressor", postcolonial whilst British. Clarke does not stem from border country; the actual border between Wales and England, as Raymond Williams, for example, did. [25] Her borders are metaphorical and, as has been seen, she uses them to explore connections and differences. She clearly refutes any simplistic labelling of a poet's identity, or indeed of a nation's, seeing instead the complexity of the human and physical landscapes and issues that forge the voice of the poet at any given moment. Her insight is into the divisions within the terms, the many different ways that exist, for example, of being Welsh, of dealing with the "fractures and sutures." [26]

[7] This is equally the case in a discussion of Clarke as a feminist poet. Her early publications in the 1970s and 1980s are generally domestic in theme and discuss her own experiences and those of her family and acquaintances, most frequently female. [27] This is, however, writing centred on her familiar world and does not exclude careful observations of the natural world and, more recently, of political issues. During the late twentieth-century she was perhaps best known for her long poem "Letter from a Far Country," [28] which presented generations of female experience, particularly of motherhood, both personal and generic. It is an alternative history of domestic work, the lives women have lived but which have lacked the prestige of historical documentation. Its presentation is lyrical, the techniques some of those well-documented as l'écriture feminine: it is anti-linear, structurally irregular apart from the regular three stanzas tacked onto the end, printed in italics and forming a song of excuse for the housewife's existence. However, it lacks jouissance; indeed, it registers the tedium and the restrictions of women's housework as well as the creativity and heritage. There are lists of the tasks the narrator enjoys, laundering, jam-making, tasks her Welsh ancestors did in similar ways:

It has always been a matter

of lists. We have been counting,

folding, measuring, making,

tenderly laundering cloth

ever since we have been women. (11)

The poem presents the positives of nurturing and providing but counteracts these with its usurped male metaphors. The busy housewife tidying up after the family's morning exodus draws "the detritus of a family's/ loud life before me, a snow plough,/ A road-sweeper with my cart of leaves" (7). It undercuts its long (typically narrative) form by telling fragments of stories and circling around its themes, dipping into history and back to the present, as water circles around stones and the current ebbs and flows. Water is perennially Clarke's dominant image of femaleness and, whilst the poem contains sections in which the female imagination and body are linked to the natural world via the menstrual tugs of the ocean's tide, this creation of female power is undermined by the wistfulness for the male's different world: "The minstrel boy to the war has gone;/ But the girl stays. To mind things./ She must keep. And wait. And pass time" (8). "Pass time"/ pastime negates the worth of the female role, reminding us of Cordelia's "Nothing"; the female symbol and the figure zero are both the circle, the marriage sign of possession. Clarke's poem documents neither a simple twentieth-century escape from the drudgery of the past or a resigned martyrdom to the kitchen-sink—"Here's a woman who ought to be/ up to her wrists in marriage/ she is shaking the bracelets from her arms" (16)—but rather an awareness of the peculiar restrictions upon a woman's personal freedom caused by the maternal body. The irony of the letter "from a far country" is that it ends "unposted," because the mother has remained at home. As the poet admits in the second stanza: [it] "might/ take a generation to arrive."

[8] It is a letter written to all men in order to explain what they cannot know: "Children sing/ that note that only we can hear" (18), and equally what they may have disregarded as unimportant. It is female writing rather than politically feminist; it posits the housewife's day into the mock male-adventuring narrative form to express difference (and historical neglect). However, much less typically feminist is Clarke's second long poem "Cofiant," [29] which comprises poems (and a few prose explanations and genealogical lists) in the Welsh tradition of family biography, all of which relate to her male ancestral line and the houses and locations connected to it. In it she celebrates her father, John Penri Williams, as she will do more personally in "The King of Britain's Daughter." On a simplistic level, then, "Cofiant" acts as a balance against the female subject-matter explored in the earlier "Letter." Michael Thurston, in his discussion of Clarke via this poem, which sites her amongst her Welsh contemporaries in the struggle to express a nationalist identity, makes the important point that, whilst the poem does explore "A Welsh recognition of the beauty of genealogy," [30] it also discovers an "absence at the heart of remembered histories, an absence that in turn empties the ideals of nation and national identity" (288). In this history of a Welsh family (an exemplar, as Thurston shows, of the history of Wales) we see the past traced through the male line, the houses families inhabited, mostly now in ruins, a history that is unable to be read.

Clarke's sea, an eternal, maternal maker of new texts, swallows the past—Clarke's father, the villages and farms inhabited by more distant ancestors, the crumbling hill-fort—cleansing memory with its wash of Atlantic salt. (297)

The sea was the dominant image in the earlier poem. "The waves are folded meticulously,/ perfectly white. Then they are tumbled/ and must come to be folded again" (11). These are the sheets laundered throughout the past by women, and the waves of West Wales' Irish Sea coast folded by, it would suggest, a female power. Clarke herself is aligned with that power—we will come to see why in "The King of Britain's Daughter"—her time is "set/ to the sea's town clock./ [Her] cramps and drownings, energies,/ desires draw the loaded net/ of the tide over the stones" (17).

[9] Current understandings of what it means for a text to be feminist problematize reading the politics of "The King of Britain's Daughter" in a way that matches its nuanced and complex rendering of female voice. The poem sequence's feminism is at risk of being denied because of its otherness to what are now deemed appropriate feminist attitudes toward gendered voice and borderland identity. There is nothing strident about Clarke's feminism; its importance is the confidence it expresses in its subject-matter: the female consciousness as the centre of the network of human relationships. Clarke does not seek to generalize from a personal predicament; rather she is always investigating the self, exploring in all directions. In her third long poem "The King of Britain's Daughter," which I shall now examine in detail, she combines the familiar elements already discussed—the autobiographical experience, the Welsh landscape, the male/ female dynamic—with a new element, the effect of myth both on the creation of the self during childhood and on the connection of the individual to her national/ racial identity.

Using myth: "The King of Britain's Daughter"

[10] An intimate connection exists between the word, the mythos, the sacred tales of a tribe, on the one hand, and their ritual acts, their moral deeds, their social organization, and even their practical activities, on the other. [31]

[11] It is almost inevitable that Gillian Clarke should have used myth in her poetry; it is such a familiar tool in the work of female poets writing in the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly in its feminist revisionary role, as advocated by Adrienne Rich, and especially where nationality is an issue. Equally, this period saw a resurgence of the use, often revision, of fairy tales, most notably perhaps in Anne Sexton's Transformations (1971), and Jack Zipes has demonstrated that the fairy tale "continues to play a significant role in the formation and preservation of the cultural heritage of a nation state." [32] The use of indigenous myth is frequently employed by writers in a postcolonial or marginal condition as a strategy of appropriation, a way of adapting what Emyr Humphreys has called "the language of the oppressor" in reference to the "english" in use in Wales. [33] Clarke's use of Celtic myth, particularly the figures and locations presented in the stories of The Mabinogion, is, as we have seen, a way of exploring her personal and national identity; however, Clarke is a female poet and myths, as well as fairy stories, can be entered effectively from the female perspective as a means of presenting a fresh insight—or, as Clarke herself describes the poet Jenny Joseph's technique, enabling the poet to "domesticate big themes and make the domestic universal and eternal." [34]

[12] Clarke's interest in and use of myth, especially Celtic myth, has already been discussed by M. Wynn Thomas, amongst others, in response to "The King of Britain's Daughter." Clarke's association of the Branwen myth, alongside the legend of Shakespeare's Lear and Cordelia, with her own relationship with her father has been discussed in detail by Thomas in his close reading of the poem "Llŷr." [35] Her awakening into awareness of her dual linguistic/ literary heritage, which is explored in "Llŷr," [36] is an additional and complementary field of meaning to the various themes explored in "The King of Britain's Daughter." This essay will explore the feminist nature of Clarke's presentation of myth, legend and fairy tale in her poem sequence and the consequences of these texts interacting with each other. Alongside the tale of Branwen from The Mabinogion, there are traces of the fairy tales of "Cinderella" and "The Little Mermaid," [37] and the Greek legend of Procne and Philomela, each of which throws additional light onto the relationship of the child in the poem with her father, who made the Celtic myth of Brân and Branwen her own personal "geography of the mind." [38] The various protagonists of these stories have different ways of resisting and defying the restrictions imposed upon them by their social milieux; what they have in common is the struggle to make their individual female voice heard in a patriarchal world. Clarke charts the development of her poetic voice in this poem by slipping and sliding through these iconic tales from European cultures, whilst registering the varying degrees of passivity these tales may engender in their reader. Of particular interest will be the differences that occur between the amount of re-telling and of feminist re-vision in her handling of the various texts, and the ways in which this connects to the national and supra-national identities of the stories.

i. In thrall in the Fforest of childhood: Branwen, Cinderella and the Little Mermaid.

Woman is the Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, Snow White, she who receives and submits. In song and story the young man is seen departing adventurously in search of woman; he slays the dragon, he battles giants; she is locked in a tower, a palace, a garden, a cage, she is chained to a rock, a captive, sound asleep: she waits. [39]

[13] Thomas's reading of "The King of Britain's Daughter" highlights Clarke's "reluctance to draw a hard-and-fast distinction between the sexes" (13), a reluctance that stems from the nurturing relationship she enjoyed with her father and that is expressed in the poem sequence as a disastrous outcome when Brân is separated from Branwen. In particular Thomas notes that poem 12, "Branwen's Songs and the Lament of Bendigeidfran," (16) ends with an "elegiac tribute to her father in the form of a beautiful epithalamium celebrating the reunion of male and female, Brân and Branwen" (13), where Brân, cupping the starling in his nesting hands, arrives to rescue his sister in a stance that reminds the reader of Clarke's father working his threadbare hat into a "form/ for the leveret" (10), the child Clarke was trying to rescue. However, the small hare died, as did both Brân and Branwen in addition to numerous Irish and Welsh involved in the conflict, and—if we move over to the Lear legend—so too did Lear and Cordelia, amongst others, in Shakespeare's play. It is not, then, a happy myth/ legend, in spite of the rescue of sister by brother. It depicts, alongside the father/ daughter relationship Clarke is indubitably using, another archetype, that of a romantic liaison gone wrong, of a heroine who loves and loses her prince.

[14] The poem indicates, as Clarke has made clear elsewhere, [40] that it was through her father that she grew up more than familiar with the Celtic legend of Branwen; this particular tale appealed so strongly to the child because her father made it personal, connecting it to the beach and cliffs she frequented whilst staying in her grandmother's house: "On the beach a few hundred yards from my grandmother's farm on the west coast of Wales is a huge rock footprint, left, my father said, by Bendigeidfran as he set off through the waves." [41]

[15] It would have been familiar, then, in the way other legends and fairy tales—"Cinderella," for example—may be embedded in the imagination of particularly receptive children. When surveys are made we are led to believe that "Cinderella" usually emerges as the female's favourite fairy tale. [42] It is universally appealing, pertaining as it does to the child's conflicts with parents, rivalry with siblings, and belief in the perfect partner to fulfil the romantic dream, and also, incidentally, of "rags to riches" for the hard-working and deserving, [43] not to mention "just deserts" for all enemies. However, the Cinderella archetype is not for the feisty or rebellious girl. There is too much penance in the kitchen and pointless picking of lentils out of the ashes whilst waiting for the miraculous transforming powers of new clothes and fancy jewels. There is also that rigid slipper which has to fit perfectly. It means that Cinderella is the epitome of feminine beauty, but it simultaneously constricts her to the prevailing stereotype of female behaviour. [44]

[16] Another well-known fairy tale presents the flip-side to "Cinderella." The Little Mermaid also has a frustrating wait before she can meet her prince but the encounter and the outcome are dramatically reversed. The ball occurs before she meets the prince and she has no lack of status; indeed, she rescues him and then courageously endures trials and painful sacrifices that would make the male heroes of legends blench. These include the loss of her tongue (and consequently her voice) as payment to the sea-witch for the potion that will transform her tail into legs—a far more drastic means of attracting the prince than Cinderella's dress, coach and horses—a change that will be excruciatingly painful on a permanent basis, and more restrictive than the glass slipper of "Cinderella." The stipulation the mermaid receives from the sea-witch, who is far removed from the conventional fairy godmother, is much more dangerous than Cinderella's midnight curfew. If the prince does not marry her, she will lose her chance of obtaining a human soul, and if he marries someone else, the mermaid will disappear completely. The mermaid's sacrifice for the possibility of a happy marriage is immense. Without her voice she is unable to convince the prince of her identity and, when he marries another princess, the mermaid is doomed.

[17] How is all of this relevant to "The King of Britain's Daughter" apart from some obvious similarities between the archetypes of Branwen, Cinderella and the Little Mermaid? The poem clearly has a strong autobiographical element, [45] and the poet presents two selves, the adult remembering and the child remembered. The adult position is not only of grief for a father, who had not been explicitly mourned, [46] but also a response to a marriage that ended in the 1970s, after which, in a move reminiscent of Branwen's return home to Wales, Clarke returned to the West Wales area, although to Blaen Cwrt not to the grandmother's house recalled in the poem. [47] The child, however, would have been unaware of the pending conclusion of the Cinderella dream. The same childhood activities, swimming in the Irish Sea, playing in the wrecked boat on the beach, that initiated escape into the Branwen story also activated memories of the Little Mermaid, the tireless and graceful swimmer who rescued the prince from his wrecked ship, and who, again like Branwen, both lost/ left her father and then lost her prince.

[18] Additionally, the child's male hero is Brân, huge, nurturing and rescuing, qualities more typical of the child's view of her father than her future lover, and it is the loss of her father that is at the heart of this poem. The "bruise that will not heal" made by Bendigeidfran's stone, the Rocking Stone that fell from the headland to the beach at some point between Clarke's childhood and the writing of the poem, Brân's slingstone (1), is also the "Apple out of legend," with connotations of both Eve and the Island of Apples, combining the Arthur legends with those of Brân. [48] This linkage of Brân with stone and with her father leads inexorably to the father's grave stone and therefore his death, causing "the bruise that will not heal." Catherine Fisher has commented that the contrasting of Clarke's fairly safe childhood (as presented in the poem) with the Brân legend conveys it as "fragile and precariously poised," [49] a precariousness Clarke expresses by "A finger would rock it" (1), inevitably conjuring the image of a rocking cradle. This is confirmed by poem 2, in which Clarke is rocked to sleep in her father's Austin wrapped in his coat, a security from which she would be periodically jolted awake on a journey to this place of legend that was paradoxically both a haven of natural beauty, echoing the safety of generations of family, and a place of unease and anxiety for the poet, possibly reflecting the threat that was omnipresent during the Second World War years, when Clarke was virtually an evacuee there. The feeling of unease, however, might also suggest a child's anxiety at being separated from parents or the dislocation that a monoglot English-speaking child might feel on suddenly finding herself situated in a Welsh-speaking environment:

Those rocks lying broken on the shore and jutting jaggedly from the sea still have an air of turmoil about them for me. They loom out of dark times for which I have no certain explanation, but which cast up old tales of war and shipwreck and bear messages that seem to be coded or in languages I could not understand. [50]

This adult sense of the fragility of the childhood world and the need during childhood to be conjuring escapist worlds are both connected with the use of fairy stories, as Bruno Bettelheim has shown. [51] Furthermore, the journey to Fforest (a word connected inescapably with fairy tale and legend and usually indicating the presence of dangers, trials and tribulations) appears to the child to be to a place cut off from the "real" world, separated by the "two gates that had to be opened and closed again" (2), which are reminiscent of the gates in T.S. Eliot's "Burnt Norton" and "Little Gidding," which would, in turn, link the Fforest of Clarke's childhood with Eliot's rose-garden, [52] whilst ironically undercutting the reference by its connection with the po under the oak bed:

Then the deep cloud-cold of a feather bed,

mirrors that bloomed with a damp off the sea,

and under the oak bed in the black cave

where the ghost was, and a fleece of dust,

the po, with its garland of roses.

The imagery of mirror, cave and sea is typically of Clarke and typically female; yet it is also a fairy tale setting of feathery cold clouds, of blooming mirrors, like the sea-weedy mirror of the Little Mermaid, of ghosts and legendary fleece, and the badge of the heroine—a garland of roses, the illustration found on every old copy of fairytales.

[19] Poem 3 sets a more prosaic scene of the grandmother's industrious housework; but the cat's tail rising from her fire conjures up the witches and old crones of fairy tale, whilst the fire itself presents the untransformed Cinderella, alongside Branwen relegated to the kitchens. That Clarke is aware of this period and place as having a psychological effect is clear from poem 4 with its reference to the cave and shouting in the dark. Poem 5 is ostensibly about the child's relationship with her father, the radio engineer and alternative hero of the poem: her dressing up in his clothes, her memories of rambles in the countryside and in particular the time he used his hat as a bed for a dying leveret. This poem is key, however, for an understanding of the connections between fairy tale and myth in Clarke's childhood. In the poem "Llŷr," Clarke admitted the familiarity of the Lear/ Cordelia pattern in this relationship, doubled with her connection of Lear with Llŷr, of the British myth with the Celtic. Here her father is the old king, his hat with "the gold words faded like old books/ inside the headband" is the crown given away, and she, the daughter, is too small to take his place: "His hat covered my eyes/ and his coat dragged in the grass." The structure of the poem leads us further into fairy tale. It has five stanzas, four with three lines and the second—inevitably emphasized—comprising only one line, a line meant to give pause, to shock: "When she gave it away." Clarke blames the mother for giving away the father's clothes and with them a part of Clarke's childhood, and for not treasuring every memory of the father. This removal/ denial of the father by the stepmother is typical of many fairy tale scenarios, including Cinderella. Commentaries almost universally point out that the wicked stepmother's taking over from the "good" birth mother and showing hostility towards the female protagonist is less a comment upon actual step-parenting than upon the change in the attitude of the developing girl towards her mother. [53] Nevertheless this idealization of the father and resentment of the mother are not typically feminist; a more usual feminist technique would be maternal endorsement and appreciation of matrilineal heritage—the glorification of a revised Eve.

[20] As the poem-sequence progresses, the connections between fairy tales, myths and personal circumstances are drawn tighter:

When the world wobbled

we heard it on a radio chained

by its fraying plait of wires

to the kitchen window-sill (6)

The women are in the kitchen—Cinderella, Branwen and Clarke—chained by their plaits to the kitchen sink and listening to the radio, the specific sphere of the father, "the radio engineer"—and of Lear/ Llŷr with its "Bakelite crown." The patriarchal message they hear, the repetition of "w," indicates the world is at war: for Branwen it is war between her brother and the King of Ireland, her husband; for Cordelia, her French soldiers supporting Lear against his other daughters; for the child Clarke it is the Second World War; for the author Clarke, it is the Gulf War. The news received, the "incoming shadow/ of rain or wings," is both the aircraft flying low over Ceredigion and Branwen's starling, indicating that Clarke's grandmother's house is situated (in her personal myth) near Brân's base where he heard of Branwen's shame. In the actual myth Brân received the starling at Caernarfon and his base was at Harlech nearby.

[21] Clarke sets off on her own rescue mission retracing Brân's foot prints "making for open sea/ past headlands like drinking dragons" (8), the West Wales coast. The child Clarke is in a beached wreck of a houseboat, full of her fishy treasures and "maps for the journey." She names herself "the King of Britain's daughter," Branwen and Cordelia, but also Gillian, because her personal marker, the "neolithic stone" up on the headland is "from the giant's pocket"—the stone dropped by Brân, although the "pockets too deep to fathom" were those of her father (5), that rocking stone, "apple out of legend" (1) that tempted Eve. Whereas Branwen waited, like Cinderella, a fairly passive female, Cordelia set off from France to rescue her father, and the Little Mermaid swam out to the wreck to rescue the prince. Clarke, the mermaid, is a strong swimmer—"Seal's head in water" (4)—and she is finding the words that Cordelia lacked, the "renewed refusals" given to "the more recent dead,/ Those we are still guilty about" ("Llŷr" 79).

[22] The individual poems begin to increase in size from 9 onwards, crescendoing to 11, a set of four poems on her father, Penri Williams, and 12, which is itself divided into six parts and comprises the most substantial re-telling of the Branwen myth through the voices of Brân and Branwen. Poems 13 to 16 then gradually decrease in size again, the whole forming a sequence that moves from personal/ present to third person (public)/ past and back again with the intermediate poems illustrating the variety of ways in which personal and public worlds may be interlinked. Poem 9, "Giants," takes the reader in more detail over old ground, the connections between giants of myth, such as Brân, and the personal giants, the child's father, for example. Clarke concentrates upon the transforming effect of such giants—"They are the metaphors that shift the world" (9)—illustrating that the "real" world's cromlech is a mere milking-stool to Brân, a boulder his grain of sand. The "giant" parent makes things of terrifying size to a child graspable and domestic, and conversely transforms the mundane into powerful symbol. The characters of Clarke's myth merge with the Blue Stone Circle of the nearby Preseli mountains, which the child imagines lolling "on skylines,/ their heads in the clouds," as was hers in the beached houseboat which she sailed in her imagination. At the time of the poem's creation, Clarke heard the Concorde pass overhead nightly, and she uses the same transformation techniques as an adult; Concorde mutates to tern, and the boom is Brân's foot stamping, making "a black space in the stars." [54]

ii. Branwen and Bendigeidfran—the core archetype

And meantime she reared a starling on the end of her kneading-trough and taught it words and instructed the bird what manner of man her brother was. [55]

[23] Poem 12, "Branwen's Songs and the Lament of Bendigeidfran," presents the myth differently from the references and metaphors used previously. The six individual poems are expressed in Branwen's voice, although some stanzas could equally be the voice of the poet in present-day Wales. In addition, the stanzas in italics at the end of poems ii, iii, iv and v are in Brân's voice, and contrast markedly with their wild emotion, grandiose claims and masculine violence in the egocentric account of his journey towards his sister. Branwen begins in a reverse-fairy tale opening: "When the King of Ireland/ tired of me," listing—in both a female and fairy tale manner—everything that has been taken from her, before suddenly using rhyme to describe the finality and pathos of what she now has:

They gave me the scullery,

the servants' cruelty,

a stone floor,

a bed of straw. (13)

The role is pure Cinderella, but many of the details—the "bed of goosedown," the sudden waking, the world lurching, the imminent war [56] —are details we have already noted in the poet's own child life. "My drowned country" is Wales, Clarke's and Branwen's, and refers to both the Sinking Lands Brân crossed to reach Ireland, the tall forests that, legend has it, linked Caernarfon to Anglesey, and to Welsh legends about Cantre'r Gwaelod, the land drowned beneath Cardigan Bay, which is Clarke's territory as well as the sea dividing Brân from Branwen. There is no doubt, therefore, of the identification with Branwen, but there is also the suggestion of identification with Brân, chiefly because he is on the Welsh coast setting off for Ireland and the child Clarke is playing on the Cardigan beach in the beached boat. Thomas has discussed this aspect of the poem, the androgynous imagination of the female poet, in detail, attributing Clarke's reluctance to share in the polarizing of male and female (typical of much feminist poetry of the late twentieth-century) to both the relationship which the child had with her father, who nurtured her creativity and her Welsh identity, and to the poet's loyalty towards her nation, which would include the Welsh-speaking community that Thomas describes as "a permanently beleaguered remnant." [57] Clarke's sensibility is such that she maintains a careful balance between a feminist bolstering of the status of the female in Wales without, in Thomas's words, "destroying the fragile integrity of her people" (16). There is, nevertheless, a further way in which Clarke may have connected with Brân—his anger:

Oh, my face is salt,

my anger the flung sea.

Under my fist the waves are wild swans

beating out of black mountain lakes.

The spume flies up before my thighs,

serpents and burning flags and tattered sails. (13)

Clarke has touched on this in her comments on her visit to Stratford to see Lear, and her connection of Lear with Llŷr, the father of Branwen. [58] She responded to the performance, both to the language and the emotions: "A guilty, wilful daughter, an angry, stubborn father, and their reconciliation that came too late." [59] There may be anger here, both with herself and with the fate that deprived her of a parent before it could have been expected. However, there are other angers involved. In her various writings on the production of this poem Clarke has sought to express the complexity of poetic inspiration, particularly that which stems from childhood memories and the subconscious. Her imagination was richly forged out of the experiences, relationships and locations of her early years: the positives of "tall tales," mythic landscapes on her doorstep, and the love of words and stories combine with the negatives—childhood fears, when parents quarrelled and hatred was stirred up in people during the Second World War, particularly of the "monstrous enemy leader," Hitler. [60] Both kinds of warring were associated by the child with the figure of Brân and "his policy of revenge under those black skies of the early 1940s." The fact that Clarke had a place of her own in the myth and that its geography was her own presumably made intense personal connections for the child with the large-scale war occurring in the wider world, which in turn would have given the figures of myth even greater potency. The separations that occur when a marriage ends, alongside inevitable angers, must also have resonated with strands of this personal myth before the writing of the oratorio.

[24] So "my face is salt" belongs to the child on the beach, like Brân facing the Irish Sea, and to a grieving woman, with a rage stemming from hurt, like Lear's, as well as the desire for revenge on the King of Ireland, the bad husband, that Brân is feeling. Out of this temper vented on the sea "under my fist" a tempest is created in words [61] that connect the great poetry of Yeats ("wild swans/ beating") [62] with the landscape of Wales, the "black mountains." The poem itself is indicating how it was forged. As Brân strides out through a knee-deep ocean, "the spume" flying up before his thighs is not so much a suggestion that his rage is fuelled by his sexuality as that male testosterone "flies up" / throws up the images of "serpents and burning flags and tattered sails" that evoke the seminal wars of myth, history and literature, from the original sin of Adam and Eve, by way of legends of romantic separation, such as Tristan and Iseult, to the destruction of armadas and modern fleets. This, then, is not merely a poem in which a poet's native myth is combined with her personal life, it is one in which destructive familial relationships contrast and coincide with wars between nations—it is a poem about war and its causes.

[25] Branwen's voice is that of the female victim, passive and reflective in poem iii. Her identification of Brân with the sun links him not only with Christ but with other major gods, and emphasizes his maleness in the sun/ moon opposition. Simultaneously Clarke's similes and metaphors suggest that there may be personal links here, that the pebble-skimming, for example, relates to her own experience, as well as Brân's rocking stone resting on the cliff-top, as the pebble here rests "on the sill/ of the sea" (14), during her childhood. Brân, heading towards her through Cardigan Bay, treats it as he would treat the scullery in which she is imprisoned, smashing it, stamping the imprint in rock, which has been Clarke's way into the myth since childhood. The difficulty Clarke has with any war, whether ancient, the Second World War or present-day war in Iraq, is evident in her metaphor of Brân's crushing the world like a baby's skull in his "raging hands." The presentation of the heroic male is full of ambiguity; he creates the beautiful coastline of West Wales but his violence is untempered.

[26] In poems ii and iii the windowsill is mentioned, in poem iv the window itself. Each time Branwen is framed as the submissive female "other." The starling befriends her in legend because, like Cinderella, she is unjustly treated and, like the little white bird that fulfils Cinderella's wishes in the Grimms' version, it enables the attempt to resist the oppressor to come true. Branwen's isolation has silenced her, linking her with Cordelia, who chooses to say nothing, the tongueless mermaid who cannot speak, and with the myth of Philomela, whose tongue is cut out to prevent her from describing her rape by her brother-in-law, another King, and whose sister comes to the rescue before they are both turned into birds. Branwen's resistance is in telling her name until the starling is able to repeat it to Brân, whereas the mute mermaid is unable to speak. Clarke continues to express the enormity of his rage by the transformation of size: "ships are gull feathers" (15), wrecks are crabs he will step on and crack, whilst her own rage has been suppressed: "the drowned rocks of my rage" (15). [63] A storm brewing in Ireland warns Branwen that her brother is coming, whilst the stories of islands, trees and lakes moving towards the coast remind readers of another Shakespearean tragedy and prepare them for the outcome. Both voices use the word littoral as Clarke puns on literal, stressing the real rather than metaphorical size of the hero whose ships are the size of hunting hounds at his ankles.

[27] The final section of poem 12 is one brief stanza in which the sister describes Brân and her trust that he will rescue her. Her patterned alliteration and the descriptive phrases—"a black crow/ blessed and iridescent"—that translate his Welsh name, Bendigeidfran, into English present him as giant, prince and brother, ignoring the violence and destruction and seeing only the gentle rescuer "with a starling/ cupped in his nesting hands" (16), an image that links Brân absolutely with Clarke's father and the nest for the leveret (poem 5 (5)), [64] illustrating that perception can be blinded by love. In the preface to the poem Clarke recounts a summary of the myth, omitting the scenes of violent slaughter in Ireland in the full version from The Mabinogion, which includes the slaughter of Gwern, the son of Branwen and the King of Ireland.

The Two Kings by Ivor Robert-Jones (1984) situated near

Harlech Castle.

Bendigeidfran carries the body of his nephew Gwern.

[28] In the oratorio we move from the picture of Brân arriving in Ireland straight to the poet's description of Branwen's grave, poem 13 (17), the conflict having been completely ignored. [65] The window has now become a mirror, the "broken mirror" of an unfrozen river, with Branwen's death, but her presence is described in the long green hair of the swirling river plants, the weeping of water moving over stone, "the crumpled face of water", "the sob of wind" and the "cry of water-birds." [66]

[29] The tempo lifts in the second two stanzas as the poem moves out of water and into air; the "tambourine of birds" whirrs with her name, countering the silence, and spring returns: "the ash is leafed again, / the starling tree." Again the use of the tree reminds us of Cinderella's tree and her association with cinders/ ash, which gave her her name, and the earlier name "Ashputtle," the ash originally connecting with penance rather than dirt. "Her name / on the tongue of a bird" links—via Procne and Philomela—with the nightingale, the Keatsian symbol of poet/ry, which is what is left of Branwen for Clarke.

iii. The Little Mermaid

Every step you take will feel as if you were treading on a sharp knife, enough to make your feet bleed. [67]

[30] References to Hans Andersen's "The Little Mermaid" exist throughout the text but poem 10 centers on that fairy story, one that haunted Clarke's childhood (10). [68] Allusions in the poem dance between King Lear, "The Little Mermaid" and Adrienne Rich's "Diving into the Wreck," as the adult Clarke has a sudden realization about the relationship between her mother and father years earlier. The poem's voice is ambiguous, appearing to move between adult poet, poet as child and mermaid, although in the oratorio as a whole the "I" is usually the poet as adult. The physical descriptions of the bay near Fforest in which Clarke swims encourage the reader to imagine that tricks of light on the land/ seascape trigger memories of the mermaid in the fairy tale. "The sunken wreck/ in which I'm trapped in dreams" conjures a web of reference from the childhood boat beached in reality, submerged in nightmare, through the wreck (featured in the fairy tale) from which the mermaid rescues the prince, to the wreck of Rich's poem: [69]

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

Rich's wreck is a separate complex symbol with references ranging from The Tempest to Jacques Cousteau's underwater television programmes by way of various versions of "The Little Mermaid," including Arnold's "The Forsaken Merman," as Rich investigates the validity of the patriarchal myth inside which modern society, Rich's WASP culture of North America, still operates. [70] In Clarke's dream, "in a fishtail gleam/ she leans to kiss me as she goes/ dressed in her glamour to a Christmas dance." Clarke is flitting between dream images of the mermaid going to the court ball in her father's castle under the sea and a Cinderella-like child's memory of a goodnight kiss from a mother dressed up for an evening out, a memory in which glamour becomes "fishtail gleam", and mother a mermaid. Later lines: "I suddenly knew she slipped him, that he carried like an X-ray/ her shadow picture" suggest "The Forsaken Merman," whose wife leaves the sea family for a separate life ashore, but may refer to the little mermaid who loses her prince, or Clarke losing father and/or husband, and if they do the situation has been reversed—she slips him. "I suddenly knew" implies a revelation on Clarke's part, about her mother escaping her father, herself escaping her husband, Branwen escaping brother or husband, mermaid escaping father and then losing prince—the permutations are endless. The revelation occurs when "Nothing" breaks the surface of darkness (consciousness/ memory) or sea (the beached boat of childhood has disappeared). "Nothing" harks back to Cordelia and the "nothing is until it has a word" of Clarke's "Llŷr."

[31] The poem occurs as the poet treads water in Cardigan Bay, looking back at land. The beginning of each of the three six-line stanzas sets the scene: "I swim far out"—"I"m cold as sand"—"The tide lifts and lets go." However, the two two-line stanzas are less explicit. They evoke the disastrous Titanic, as the shark descends not the stairs of Rich's wreck but "the staircase of the liner." [71] The shark in the former stanza becomes "something gleaming" in the latter, yet the first trace of "gleam" was the fishtail of the mermaid, now only a trace in "deepest water." The former stanza has the impotent character of nightmare scenarios; in the latter the nightmare threat is less obvious (the shark is an obvious candidate for a Freudian phallic symbol) [72] but still glimmering at the edge of the poet's vision.

[32] The introduction of the fairy-story into the sequence of poems already drenched with myth is intriguing. Even if it did not have personal significance for Clarke, "The Little Mermaid" is a clear signifier of the adult and child narrator loving to swim in the sea, in addition to working as wish-fulfilment for Branwen, looking over the Irish Sea in longing during her imprisonment. As a narrative it bridges the gap between happy-ever-after Cinderella tale and the tragic outcome of "Branwen" and Lear. Andersen's tale is a moral one, enticing children to be good, in order to lessen the time it will take for the mermaid to earn her soul. [73] The mermaid does not "get" the prince, but she finds that her unselfish, brave actions have enabled her to become a child of the air, [74] have given her another chance at a different kind of happiness, and this may have had appeal for Clarke at the time of writing "The King of Britain's Daughter." However, it should not be forgotten that at the heart of "The Little Mermaid" story is female damage: the physical pain of female sexuality (whether this refers to the sacrifices involved in conforming to stereotypical ideas of female beauty or the pains of puberty and penetration) and the silencing of the female voice, which is a prerequisite of heterosexual marriage in a patriarchal society. The mermaid's singing voice was her greatest attribute, and she sacrificed it to the hope of marrying her prince—a frightening concept to a child with the potential of becoming a poet. Indeed, if for a moment we consider this a poem charting the end of a marriage, the emphasis on the role of Branwen, who finds a voice in order to escape from her isolation and imprisonment, over Cinderella, who found happiness in the restrictions of marriage, and the mermaid, who accepted a maiming silence in order to obtain her prince, becomes clear.

Conclusion—vision and/or revision

Every telling of a myth is part of that myth: there is no Ur-version, no authentic prototype, no true account. [75]

[33] Llŷr or Lir was the Welsh God of the Sea, not the King of Britain (despite this being Lear's title in Shakespeare's play and in lists of legendary kings of Britain, Holinshed's Chronicles, Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of England, Spenser's The Fairie Queene and the anonymous play King Leir, usually cited as a main source of Shakespeare's King Lear). Although the myth of Branwen is very much the theme of the whole poem, the title suggests that Clarke, the daughter, is more Cordelia than Branwen. The story "Branwen Daughter of Llŷr" in The Mabinogion opens with the information that "Bendigeidfran son of Llŷr was crowned king over this Island," [76] indicating that Brân is also the King of Britain. Clarke is, moreover, the daughter of Brân in that her father, Penri Williams, is linked, as we have seen, more closely in type with Brân than either Lear or Llŷr. As "Radio Engineer" (11-2) he is mythologised as a man in contact with the stars, the only one mentioned being Orion, [77] who has strong associations with Brân [78] in also being the son of the God of the Sea, here Neptune, gigantic in stature, with the power, given to him by his father, of wading through the depths of the sea or walking on the sea's surface, as Brân is frequently described by Clarke. (79)

[34] Clarke is using a variety of myth sources in the creation of the poem. The image of her father as fisherman unreeling his line and casting syllables at the sky is both Christ, who also walked on water, and the hunter Orion, and conveys more than the sense of the child hero-worshipping her father; Clarke the adult is not afraid to place her own early memories of a larger-than-life parent alongside the gigantic heroes of myth and legend in a poem-memorial that takes the place of the hoard she collected as a child in the graveyard, including "an alabaster dove with a broken wing" to remind us of that hat/nest and the cupped hands of Brân. [80]

[35] Alternatively, the loving but absent and ineffectual fathers of fairy tales are a complete contrast to the demanding, powerful and egotistical Lear. However, Shakespeare's Lear can also be read as a treatise on the ways in which daughters can destroy a father. The patriarchal world wobbles when the patriarch has only daughters and will not allow them autonomy. Whether the daughter rages like Goneril or is silent like Cordelia, the old king is driven to madness and confusion. Conversely, the modern-day images of Clarke's father in the poem are affectionate and safe; the dominant impressions are of the female child dressed or wrapped in the man's clothes, revelling in the lore passed on by the father. Male/ female discord only enters the poem when Branwen is rejected and humiliated by her husband, the King of Ireland.

[36] We have seen the variety of texts used by Clarke in the composition of her oratorio; this essay began with the notions of using myth as a postcolonial strategy and of feminist myth revision. What then is Clarke achieving with her mixing of Celtic myth with fairy tale, classical myth and childhood memory? We know that the poem was commissioned as an oratorio on the Branwen myth by the Hay-on-Wye Festival and that it began in 1990 when Clarke and five other poets were given a day to write something on the topic of "Border: Fatherland, Motherland." [81] We have seen the reasons why a female poet committed to her Welsh heritage might avoid "all-out" criticism of the patriarchal nature of that society. However, the range of stories she has chosen to use has in common the presentation of social stereotypes for females as restrictive, painful and destructive. At the heart of each plot is the frightening silencing of the female voice, which happens when the female compromises herself for male approval, epitomised by the mermaid's hidden agony when dancing with the prince. Whereas Clarke is explicitly portraying the positive elements in the father/ daughter relationship in the autobiographical passages, she is also exploring the dynamics that caused the "stormy love-connections" [82] resulting in the suppressed grief at her father's death. The fairy stories work, as Bettelheim has explained their function for children, in that they expose the core problem and help with its resolution. [83]

[37] In returning to the beach of myth and childhood with a new partner, to whom the volume is dedicated and about whom the final poem is (presumably) written, Clarke is both moving forward and returning to old ground. Her talisman pebble (Brân's rock) is now in her, not her father's, pocket—the explicit message is that the female now has within her own control the power and care once sought from the male. However, as the couple watch a romantic sunset—"the sun stood/ one moment on the sea/ before it fell" (20)—the reader may skip back pages to find Branwen imprisoned in the scullery looking towards Wales and ponder on the patterning archetypes in this poem, which suggest that situations are often repeated, that the poet is indeed aware of the dangers inherent in "institutionalized heterosexuality," to use Rich's phrase: [84]

Pebble of amber,

it rests a moment on the sill

of the sea before describing

its long, slow arc. (14)

Clarke's use of the Branwen myth in her oratorio feminizes it in dealing with the Branwen situation and avoiding the warring male confrontation in Ireland; it also modernizes and personalizes it in that she combines the original Celtic myth with her personal experiences half a century ago and present day. However, the use is more postcolonial than feminist in that the myth is not thoroughly revised or entered from a radically different perspective, as myths are in revisionist poetry by Carol Ann Duffy, for example, or as the Lear story is by Jane Smiley in A Thousand Acres; [85] rather it is, as was suggested at the beginning of this essay, used as a strategy of appropriation, a method of asserting the nationality of the author.

[38] Clarke has defined what poetry is for her: "a rhythmic way of thinking, […] a thought informed by the heart, informed by the body, informed by the whole self and the whole life lived, so that being a woman and being Welsh are inescapably expressed in the art of poetry." [86] As Thomas has already explained, [87] it can be construed that this combination is inherently paradoxical; that is, Clarke has no desire to radically alter a myth that is so significant for her personally as it stands, and, further, raise any criticism that would reflect negatively on her affirmative presentation of Welshness—which is where the use of fairy tale texts becomes crucial. Fairy tales have their own inherent paradox as Joyce Carol Oates, amongst others, has clearly demonstrated. [88] On the one hand "the very expression fairy tale calls to mind a quintessential female sensibility; the tales are old wives" tales, Mother Goose tales" (1). On the other hand, fairy tales, as a general rule, endorse a very patriarchal, hierarchical world-view:

What is troubling about the fairy-tale world and its long association with women is precisely its condition as mythical and stereotypical, a rigidly schematised counter world to the "real"; … as if women are fairy-tale beings yearning for nothing more than material comforts, a "royal" marriage, a self-absorbed conventional life in which social justice and culture of any kind are unknown. (3)

Clarke's addition of such texts as "Cinderella" and "The Little Mermaid" to "The King of Britain's Daughter" subtly injects a comment on the cruelty of patriarchy without detracting from the positive use of indigenous myth.

[39] The texts reused in "The King of Britain's Daughter" may have been chosen because they are embedded in the poet's store of earliest memories; in other words, the poem is not so much the retelling of a myth but an exploration of one poet's geography of the mind. Nevertheless the poem also works as a discussion of the present Welsh condition: whilst a literal reading provides a paradigm of the English-speaking Welsh female's situation, a metaphorical reading provides a commentary on the "post-national" state of Wales described at the beginning of this essay. Heterosexual marriage in a patriarchal society, with its inherent inequalities, bears some equivalence to the colonial integration of small nations: whether internal colony or dependent periphery. The heterosexual marriages presented in these texts—restricted (Cinderella's), unachieved (Little Mermaid's) or disrupted (Branwen's)—may equally serve as paradigms for the differing possibilities for the borderland existence of the marginalized nation. Clarke's emphasis on Branwen's story at the expense of the others may indicate her own preference.

[40] Gloria Anzaldúa has discussed the imperative for modern societies of the creation of "a new mythos":

En unas pocas centurias, the future will belong to the mestiza. Because the future depends on the breaking down of paradigms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos—that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave—las mestiza creates a new consciousness.

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in or best hopes, bring us to the end of rapes, of violence, of war (102).

Clarke, we have seen, is re-telling a Celtic myth, one of the core texts of Welsh culture. Hers is a new version; it contains her story, other influential tales from the wider British and European cultures of which she is also a part, and a revised text, not revised in the usual feminist manner—as Jane Smiley, for example, has updated the Lear story in A Thousand Acres, switching the perspective to that of the Goneril figure, empathizing with patriarchy's hag [89] —but by omissions. In ignoring the violence and treachery perpetrated by the male characters, in almost removing the sense of Britain at war with Ireland by concentrating on the personal relationships of Branwen with husband and brother, and further by investing her child subject with the ability to imagine herself Brân as well as Branwen, Clarke is moving towards Anzaldúa's notion of "healing the split," of ambiguities rather than dualities, of discontinuing old animosities, and is introducing a new "mythos." There are many similarities between Clarke and Anzaldúa: their concern for their native language, their respect for the ancient matrilineal cultures embedded in their race's history, their feelings of rebellion—which exist alongside the borderland identity already discussed. However, characteristics that may encourage the dismissal of Clarke as a feminist poet: her heterosexuality, her positive presentation of domestic situations often considered subjugated, and the nostalgic love for her own father which resonates throughout this poem sequence, should not be allowed to obscure her contribution to the mapping of female identities.

Acknowledgements

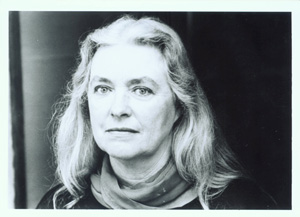

I would like to acknowledge with thanks the use of photographs from a variety of sources, particularly those by Anthony Griffiths, which are taken from The Mabinogi: Legend and landscape of Wales. Trans. John K. Bollard. Llandysul: Gomer, 2006. ISBN 1 84323 348 7. I am grateful to Gillian Clarke's publisher, Carcanet, for the photograph of the poet and the covers of her books. The Pembrokeshire coast (by Donar Reiskoffer) and The Two Kings are from Wikipedia.

Notes

[1] Edward Said, The Edward Said Reader, Eds. Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin (New York: Vintage, 2000). xiv.

[2] Anne Stevenson. The Powys Review 17 (1985) 64.

[3] Gillian Clarke, "The King of Britain's Daughter." The King of Britain's Daughter (Manchester: Carcanet, 1993) 1-20.

[4] Gillian Clarke, "The Poet's Introduction", Six Women Poets, ed. Judith Kinsman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992) 1.

[5] See, for example, Nine Green Gardens (Llandysul: Gomer, 2000) on the restored gardens of Aberglasney; "The Fall," Making the Beds for the Dead (Manchester: Carcanet, 2004) 69.

[6] See, for example, selected articles by Kenneth R. Smith: "The Portrait Poem: Reproduction of Mothering," Poetry Wales 24:1 (1988) 48-54; "A Vision of the Future?", Poetry Wales 24.3 (1989) 46-52; "Praise of the Past: the Myth of Eternal Return in Women Writers," Poetry Wales 24.4 (1989) 50-58; "The Poetry of Gillian Clarke," Poetry in the British Isles: Non-Metropolitan Perspectives. Eds. Hans-Werner Ludwig and Lothat Fietz (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1995) 267-281.

Other selected articles (excluding reviews): Gillian Clarke, "Beyond the Boundaries: A Symposium on Gender in Poetry," Planet 66 (Dec/Jan 1987/8) 50-61; M. Wynn Thomas, "Starting to Mind Things: Gillian Clarke's Early Poetry," Trying the Line: A Volume of Tribute to Gillian Clarke. (Llandysul: Gomer, 1997) 44-68; Linden Peach, "Incoming Tides," New Welsh Review 1 (1989) 75-81; Linden Peach, "Igniting Pent Silences," Ancestral Lines: Culture and Identity in the Work of Six Contemporary Poets (Bridgend: Seren, 1992); Lyn Pykett, "Women Poets and 'Women's Poetry': Fleur Adcock, Gillian Clarke and Carol Rumens," British Poetry From the 1950s to the 1990s: Politics and Art , (Eds.) Gary Day and Brian Docherty (London: Macmillan, 1997).

[7] For example (and excluding reviews):

Michael Thurston, "Writing At the Edge: Gillian Clarke's Cofiant," Contemporary Literature 44. 2 (2003) 275-300; Linden Peach, "Wales and the Cultural Politics of Identity: Gillian Clarke, Robert Minhinnick, and Jeremy Hooker," Contemporary British Poetry: Essays in Theory and Criticism, (Eds.) James Acheson and Romana Huk (State University of New York Press, 1996) 373-396; Jane Aaron, "Echoing the (M)other Tongue: Cynghanedd and the English Language Poet," 'Fire Green As Grass': Studies of the Creative Impulse in Anglo-Welsh Poetry and Short Stories of the Twentieth Century (Ed.) Belinda Humfrey (Llandysul: Gomer, 1995) 1-23; Jane Aaron and M. Wynn Thomas, "'Pulling You Through Changes': Welsh Writing in English Before, Between and After Two Referenda," M. Wynn Thomas (ed.), Welsh Writing in English (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2003) 278-309; John Kerrigan, "Divided Kingdoms and the Local Epic: Mercian Hymns to The King of Britain's Daughter," Yale Journal of criticism: Interpretation in the Humanities 13. 1 (2000) 3-21.

Below is a selection of interviews/ articles expressing Clarke's own views with particular connection to "The King of Britain's Daughter": "Voice of the Tribe," Regionalität, Nationalität und Internationalität in der zeitgenössischen Lyrik. Lothar Fietz et al (eds.) (Tübingen: Attempto-Verl., 1992) 168-175; "Writer's Diary," Books In Wales (Spring, 1993) 4; "Tall Tales Remade," PBS Bulletin (Summer 1993) no 157; "Beginning with Bendigeidfran," Our Sisters' Land, (Eds) Jane Aaron, Teresa Rees, Sandra Betts, Moira Vincentelli (Cardiff, UWP, 1994) 287-293; "Interview," The Urgency of Identity: Contemporary English-Language Poetry from Wales. David T. Lloyd (Evanston: Illinois: Triquarterly Books, Northwestern University Press, 1994) 25-31; "The King of Britain's Daughter," How Poets Work, (Ed.) Tony Curtis (Bridgend: Seren, 1996) 122-136; Deryn Rees-Jones, "The Power of Absence," Planet 144 (2000-1) 55-60.

[8] M. Wynn Thomas, "Place, Race and Gender in the poetry of Gillian Clarke," Dangerous Diversity: Changing Faces of Wales (Ed.) Katie Gramich (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1998) 3-19.

[9] It should be noted that as recently as 1994 Jane Aaron wrote that: "Feminism is still frequently viewed with suspicion by Welsh-identified communities as an alien and divisive Anglo-American phenomenon" (183). She goes on to argue that, since the seventies, a "resurgence of confidence in Welshness" (184) has enabled "a new and strong female voice within Welsh culture." This is precisely the time of Clarke's emergence as a poet. Jane Aaron, "Finding a voice in two tongues: gender and colonization," Our Sisters' Land: the Changing Identities of Women in Wales (Eds.) Jane Aaron et al. (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1994) 183-198.

[10] M. Wynn Thomas. "Place, Race and Gender in the poetry of Gillian Clarke," 17.

[11] "From Clarke's father, then, came her abiding impulse to temper her awareness of the important social history and pathology of gender difference with a reluctance to draw a hard-and-fast distinction between the sexes." Thomas, ibid, 13.

[12] "Place, Race and Gender in the Poetry of Gillian Clarke," 7. Thomas discusses at some length the effect on Clarke's work, including specifically "The King of Britain's Daughter," of her relationship with her father in this article.

[13] See for example: Kirsti Bohata, Postcolonialism Revisited (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2004); Stephen Knight, A Hundred Years of Fiction (Writing Wales in English) (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2004); Dai Smith, "Psycho-colonialism," New Welsh Review 66 (Winter 2004) 22-29; Jane Aaron and Chris Williams (Eds.), Postcolonial Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2005).

[14] Raymond Williams, "Welsh Culture"(1975), Who Speaks for Wales: Nation, Culture, Identity. Ed. Daniel Williams (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2003) 9.

[15] Raymond Williams, "Wales and England" (1983), Who Speaks for Wales: Nation, Culture, Identity. 22.

[16] John Prichard in "Swansea and the Arts," a Radio Broadcast on October 24th, 1949 by Dylan Thomas, Vernon Watkins, Alfred Janes, Daniel Jones and John Prichard (Swansea: Tŷ Llôn Publications, 2000) 11.

[17] "For me Welsh is a second language … [and after a day working in both languages Clarke writes] At the end of the day, I'm exhausted with the effort of thinking in two languages, one which I speak well and the other which I speak considerably less well. This is what it is to be Welsh: it is sometimes bilingually confusing. It's head splitting, but it's worth it. It's an edge." David T. Lloyd, "Interview with Gillian Clarke," 27.

[18] David T. Lloyd (ed), The Urgency of Identity: Contemporary English-Language Poetry From Wales (Evanston: Illinois: Triquarterly Books, 1994) xx.

[19] Gillian Clarke, "Voice of the tribe," 168-175.

[20] Michael Hechter's ideas, presented in Internal Colonialism (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1975) were much discussed in the 1980s and 90s. Chris Williams cites N. Evans's "Internal colonialism? Colonization, economic development and political mobilization in Wales, Scotland and Ireland," Regions, Nations and European Integration: remaking the Celtic Periphery (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991) in "Problematizing Wales: An Exploration in Historiography and Postcoloniality," Postcolonial Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2005) 3-22.

[21] Not least by a 2004 E.U. map, which airbrushed Wales from the map of Europe.

[22] Gillian Clarke, "The King of Britain's Daughter," 122-136.

[23] Gloria Anzaldúa. Borderlands: La Frontera (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999).

[24] The term "Anglo-Welsh" was rejected by Welsh writers in English some years ago, due to its perceived implication of their not holding equal status in terms of their nationality with those Welsh writers using the Welsh language.

[25] Although he is best known for his critical work, Raymond Williams has written a number of novels, most of which are located in the area of his birth, the border country between England and Wales, the most famous being the first of his semi-autobiographical trilogy, Border Country (London: Chatto and Windus, 1960).

[26] John Kerrigan comments astutely on the effect of inhabiting a country which has been variously divided at different times in history in his discussion of Clarke amongst a range of other poets including Geoffrey Hill: "Like …. And less securely, Clarke, Hill uses the highly localized and sometimes strangely scaled geography of childhood to make poetry out of a recognition that to live in divided kingdoms that have been differently divided through time is to inherit a compound geography in which one locale can be variously situated and places thus be sites of transport." John Kerrigan, "Divided Kingdoms and the Local Epic: Mercian Hymns to The King of Britain's Daughter," 19.

[27] See Anne Stevenson, review of Selected Poems (1985) Powys Review 17 (1985): "She writes almost entirely from her experience, and it is her especial gift to be able to make that experience ours." 63.

[28] "Letter from a far Country," Letter from a Far Country (Manchester: Carcanet, 1982) 7-18.

[29] "Cofiant," Letting in the Rumour (Manchester: Carcanet, 1989) 63-79.

[30] Thurston quotes Linden Peach, "Wales and the Cultural Politics of Identity," Contemporary British Poetry: Essays in Theory and Criticism,(Eds.) James Acheson and Romana Huk (Albany: State University of New York, 1996) 373-396.

[31] Bronislaw Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays (London: Souvenir Press, 1974) 96.

[32] Jack Zipes, Ed. The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002) xxviii.

[33] Emyr Humphreys, "Conversation 3," Conversations and Reflections (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002) 131.

[34] Gillian Clarke. "Hunter-gatherer or Madonna mistress?" The Catalogue, Bloodaxe Books, 1986/7.

[35] M. Wynn Thomas, "Place, Race and Gender in the poetry of Gillian Clarke", 3-19.

[36] Clarke recalls in the poem a childhood visit to a production of King Lear, when she both identified with the Lear/ Cordelia relationship in Shakespeare"s text and made the connection between Welsh and English cultures via words such as Avon / Afon and Lear/ Llŷr.

[37] This connection is pointed out by Tony Conran, New Welsh Review 23 (1993) 68.

[38] "The geography of myth lies in the mind." Gillian Clarke, "Beginning with Bendigeidfran," 289.

[39] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (London: Picador, 1988) 318.

[40] For example: "The King of Britain's Daughter," How Poets Work, Ed. Tony Curtis (Bridgend: Seren, 1996) 122-136; "Beginning with Bendigeidfran," Our Sisters' Land, Eds. Jane Aaron, Teresa Rees, Sandra Betts, Moira Vincentelli (Cardiff, UWP, 1994) 287-293; "Writer's Diary," Books In Wales (Spring, 1993) 4; "Tall Tales Remade," PBS Bulletin no 157 (Summer 1993) 11-12.

[41] Gillian Clarke, "Tall Tales Remade," 11.

[42] Madonna Kolbenschlag, Kiss Sleeping Beauty Goodbye (New York: Harper Collins, 1979) 71.

[43] Critics writing on "Cinderella" are usually at pains to point out that the story is not actually a rags to riches tale. Indeed, it serves to reinforce the innate superiority of the upper classes, as Cinderella is only temporarily reduced to rags and by the conclusion is restored to her original gentility.

[44] Kolbenschlag, 1979. "The slipper, the central icon in the story, is a symbol of sexual bondage and imprisonment in a stereotype. Historically, the virulence of its significance is born out in the twisted horrors of Chinese foot binding practices." 75.

[45] Well documented by the poet herself in the articles listed above.

[46] "The idea [of writing the oratorio] released poems that had been waiting to be written all my adult life, certainly since the death of my father when I was a student, a grief I had never put to words." Gillian Clarke, "Tall Tales Remade," 11.

[47] Clarke's home "Blaen Cwrt" is named and is the setting of various of her poems, including "Blaen Cwrt." Selected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet, 1985) 10.

[48] Clarke has described the family farm "set above a small bay, a few steep fields, a wooded valley full of orchids and wild garlic, and a waterfall. I still think of it as the secret garden, as Avalon." Gillian Clarke, "Writer's Diary," 4.

[49] Catherine Fisher, "The Past and its People," Planet 104 (1994) 96.

[50] Gillian Clarke, "Beginning with Bendigeidfran," 287.