'The Girl Child of Today is The Woman of Tomorrow': Fantasizing the Adolescent Girl as the Future Hope in Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Efforts in Aceh, Indonesia [1]

Marjaana Jauhola

University of Helsinki, Finland

Abstract

This article introduces Ida, a 15 year old Acehnese girl, one of the main characters of the Oxfam International's mini radio drama 'Women Can Do It Too!', broadcast in local radio stations in the tsunami-hit coastal areas in Aceh, Indonesia in 2006 and 2007.

Various feminist queer scholars have illustrated an interface between adolescence and youth, with the wider sexed, gendered and sexualized nation-building narratives of the state. For example, Laurent Berlant (1995; 1997) has analyzed the state fetish on future orientation and illustrated how girl child stands as a "condensation of many citizenship fantasies" (Berlant 1995, 380; 1997, 58). Thus, it is not surprising, that the radio drama through its storyline repeats the statement of the Beijing Platform for Action, the final document of the fourth UN World Conference in Women 1995: 'the girl child of today is the woman of tomorrow'.

In this article I suggest that normativity could be thought of as a continuous negotiation of norms that are embodied in various localities and temporalities. Intersectionality, experiences of social inequalities. Instead of referring to intersectionality of norms as fixed and stable axes of power, it could instead be understood as expression of trauma and embodied experience (Grabham 2009).What kinds of images of tomorrow does the radio drama construct as the idealized picture for Acehnese adolescent girls? How do these images intersect with other intersecting social hierarchies? What alternative images emerge to resist dominant images of adolescent girl?

This article argues that although the storyline offers avenues to resist simplistic gendered and sexualised categorisations of adolescence outside the heteronormative frame, this opening is entangled with other social hierarchies, such as ethnicity and encounters with tsunami and conflict that gain meanings in the locally lived experiences of adolescent girls. The article further suggests that a close reading of the radio drama production offers a critique to the seemingly stabile and closed gender advocacy storyline offered by the narrator of the drama. The article suggests that adolescence could be considered as an embodied process of constant negotiation of norms.

Introduction: Build Back Better

[1] The epicentre of the Indian Ocean earthquakes and tsunami in December 2004 was a hundred kilometres off the coast of the province of Aceh, Indonesia. The earthquake and the tsunami had devastating results; lost and displaced lives, destroyed and damaged infrastructure. Eight months after the tsunami, and after some thirty years of conflict, the government of Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) signed a peace agreement on 15th August 2005 that led to a new governance law and local elections in 2006. For many, it was time to "build Aceh back better". [2]

[2] Within just a couple of weeks after the tsunami, the Indonesian government, humanitarian organizations and donor governments pledged a massive recovery and reconstruction effort, which led to reconstruction initiatives, amounting to a sum of approximately 4.8 billion Euros to be spent on rebuilding economy, infrastructure and revitalisation of human resources in Aceh between 2005 and 2009. This has included the provision of temporary shelters (initially tents, but later barracks), and construction of over 130,000 permanent houses. Many organisations add that the importance of reconstruction processes is in 'rebuilding of lost and damaged values and norms' (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 2005). So the 'better' is not understood just as reconstructed houses, roads and bridges with better quality than in pre-tsunami setting, but also as reconstructed ideas, ideals, and norms.

[3] This article introduces Ida, a 15 year old Acehnese girl, one of the main characters of the Oxfam International's (OI) mini radio drama 'Women Can Do It Too!', broadcast in local radio stations in the tsunami-hit coastal areas in Aceh, Indonesia in 2006 and 2007. The radio drama production was part of the OI's Aceh Nias Tsunami Response Programme (2005-2008) that focused on housing construction, livelihoods and public health, into which a gender mainstreaming approach was incorporated. The twelve episode radio drama production 'Women Can Do It Too!' was broadcast from June to August 2006, once a week over a period of three months on five radio stations in the tsunami-affected coastline in Aceh where the OI had ongoing project activities (Info Aceh 2007, 2-3). [3] What kinds of images of tomorrow does the radio drama construct as the idealized better futures for Acehnese adolescent girls? How do these images engage with other intersecting social hierarchies? What alternative images emerge to resist dominant images of adolescent girl in Aceh?

[4] Various feminist queer scholars have illustrated an interface between adolescence and youth with the wider sexed, gendered and heteronormative nation-building narratives of the state. For example, Laurent Berlant (1995; 1997) has analyzed the state fetish on future orientation and illustrated how the girl child stands as a "condensation of many citizenship fantasies" (Berlant 1995, 380; 1997, 58). Thus, it is not surprising that the radio drama, through its storyline, repeats the statement of the Beijing Platform for Action, the final document of the fourth UN World Conference in Women 1995: 'the girl child of today is the woman of tomorrow'. What is significant about the Beijing Conference is that it provided an international forum on how the concepts of sex, gender, and sexuality became intelligible within the context of international development aid. After the Beijing conference, it has become usual practice for UN documents to include a footnote

for the purpose of this declaration and programme of action, it was understood that the term 'gender' refers to the two sexes, male and female, within the context of society. The term 'gender' does not indicate any meaning different from the above (Desai 2005, 324).

Consequently, most of the gender advocacy documents that draw from the UN and Beijing Conference documents, insist on two genders (male and female), and do not discuss the possibility of any other gender identities (ibid). Gender equality is framed, without exception, in the context of the equality between men and women and analysed in isolation from other social inequalities.

[5] Drawing on the recently finished PhD research and fieldwork conducted in Aceh between 2006 and 2009, this article argues that although the storyline of the radio drama offers avenues to resist simplistic gendered and sexualised categorisations of adolescence outside the heteronormative frame, this opening is entangled with other social hierarchies and encounters with the tsunami and the conflict, that gain meanings in the locally lived experiences of adolescent girls. However, the article further suggests that a close reading of the radio drama production offers a critique to the seemingly stable and closed gender advocacy storyline offered by the narrator of the drama, and proposes that adolescence could be considered as an embodied process of the constant negotiation of norms.

[6] This article is divided into two parts: the first part introduces a theoretical framework for analysing intersectionality of norms and the second part analyses images of adolescent girl in the context of post-tsunami Aceh.

Encounters with Intersectionality of Norms

[7] This article suggests that normativity could be understood as an embodied process of negotiation of intersecting norms which are, however, not necessarily constructed as exclusions and opposition between self and the other, but rather, as a process of multiple becomings and intersubjectivity. Thus, I align with scholars who do "a Deleuzian reading" (Cohen and Ramlow 2006; Hickey-Moody and Rasmussen 2009) of Judith Butler's work drawing additionally on the works of postcolonial feminist and recent queer critiques of intersectionality.

[8] The starting point for conceptualising a framework for the analysis of normativity of gender mainstreaming initiatives, such as the OI radio drama production, is Judith Butler's critique on feminism that draws from normalised sex/gender division and locates 'woman' as the focus of feminist theorising and action. In 1990, Judith Butler made the argument that the category of woman achieves its stability and coherence only in the context of the heterosexual matrix in which:

for bodies to cohere and make sense there must be a stable sex expressed through a stable gender (masculine expresses male, feminine expresses female) that is oppositional and hierarchical through the compulsory practice of heterosexuality (Butler 1999 [1990], 208 footnote 206).

By focusing on norms, and the consequences of such norms, Butler suggests that it is cracks and ruptures in norms that form a basis for emerging agency and the potential for feminism and feminist politics. Thus, instead of relying on the notion of feminism and feminist politics based on the idea of a known subject, stable identity and the ideas of representation and inclusiveness, politics is understood as "a challenge and resistance to dominant and debilitating norms of gender and sexuality" (Chambers 2009, 2). The cracks 'in the system' offer new ways of understanding what feminist politics can be. Butler's ideas of performativity and subversion challenge fundamentally the conceptualisation of political agency in which identity is not only presumed to be natural (based on gender, race, sexuality) but also to be the focus of political action. For Butler, identity, instead of being a cause for political activity, is in fact an effect of power relations. According to Butler's thinking, identity categories are 'sites of necessary trouble' because, in a way, they are 'out of control' and cannot fully signify subjects. What is excluded always returns to disrupt the meaning, deferring it (Butler 1997, 301; Jackson 2004, 677). Accordingly, as Vicky Kirby puts it: "agency emerges in the interstices of those different and often competing rules and the variation of their repetition. Indeed, it is in the slippage, dissonance, or even contradiction of their repetition, that the subversion of identity becomes possible, if not inevitable" (Kirby 2006, 45). Thus, the concept of agency is "grounded in the essential openness of each iteration and the possibility that it may fail or be re-signified for purposes other than the consolidation of norms" (Mahmood 2005, 19). Agency is located within the possibility of failure or variation of repeated acts (Butler 1999 [1990], 198).

[9] Butler's ideas of subversive politics has been criticised to be limiting as it focuses on exclusions and thus maintains the idea of self/other divisions as oppositional. For example, Nancy Fraser has asked: "Is it really the case that no one can become the subject of speech without others being silenced?" (Fraser 1995, 68) Fraser's question signals an important critique of Butler's work that has been most recently taken up by Claire Colebrook (2008; 2009). Drawing from Gilles Deleuze's notions of 'becoming' and subjectivity, Colebrook makes a move away from the understanding of subjectification that is formed through constructs of self/other. Instead she suggests an understanding of queer politics that opens up "relations beyond the thinking or acting subject" (Colebrook 2009, 33, see more generally 20-22, 25-26, 28-29). Colebrook's claims focus on the perceived incompatibility of Butler's and Deleuze's respective readings of Nietzsche: force as negative (Butler) and force as positive and productive (Deleuze). Butler has been criticised for focusing on the 'negative' or constructing the self through the other or through normative violence, which relates to an ongoing debate as to whether political activism focuses on the critical exploration of normative violence that emerges from this divide between self and other. A Deleuzian feminist reading of subject formation does not rely on the self/other divide, but rather focuses on subjectifications that are in a constant process of becoming (Bell 2006; Colebrook 2008; 2009; Rossi 2007). What I find more appealing are the attempts to offer a dialogue between Butler and Deleuze through a reading of Butler's Undoing Gender as an attempt to acknowledge the possibility of performativity as multiple becomings and forms of intersubjectivity, being subjected for another and constituted as/by being "beside onself" (Butler 2004; Cohen and Ramlow 2006, paragraph 12; Hickey-Moody and Rasmussen 2009).

[10] Reading Butler's notions of heterosexual matrix has led Samuel Chambers and Terrell Carver to argue that "[t]the heterosexual matrix is nothing more, though certainly nothing less, than an assemblage of norms that serves the particular end of producing subjects whose gender/sex/desire all cohere in certain ways" (Carver and Chambers 2007, 663). Chambers suggests that the analysis of the processes and practices becomes clearer when the concept of 'heterosexual matrix' is replaced with the concept of 'heteronormativity' (Chambers 2007, 663; Chambers and Carver 2008, 137). In fact, reading Butler's work, this seems to be the move she is making when she shifts from the heteronormative matrix (1999 [1990]), through heterosexual hegemony (1993), to normativity (2004).

[11] Heteronormativity as a concept is used to refer to the dominant social order and power that maintains heterosexuality as the norm and describes it as normal in culture, society and politics (Richardson 1996, 2-9; Rossi 2003, 120). The concept emerged into the Anglo-American debate in order to describe how institutionalized heterosexuality forms a 'model of being' that appears as assumed, naturalized, as the only accepted and aspired model through discursively constructed social practices (Rossi 2006, 18). Rossi (2006) points out, however, a significant problem in using the concept of heteronormativity: its use allows analysis of inclusions and exclusions that take place related to norms of gender and sexuality, yet at the same time the concept does not pay attention to other constructs of social inequalities (Rossi 2006, 26). As pointed out by Ange-Marie Hancock (2007a), "focusing on just one social differentiation, such as gender or sexuality, ignores the possibility that more than one social category play a role in constructing social inequalities and experiences of discrimination" (Hancock 2007a, 251).

[12] Thus, to name Butler's contribution as a 'politics of heteronormativity' [4] unnecessarily limits what the analysis of normativity could otherwise offer. Throughout her books, Butler actively engages herself in a dialogue with the writings of Gayatri Spivak and Gloria Anzaldúa, and provides an interesting critique of the understanding of intersectionalities as 'enumerative categories' or 'hierarchical rankings' suggesting an understanding of social oppressions as 'plurality of identifications', 'imbricated in one another' and as a crossroads that is the 'unfullfillable demand to rework convergent signifiers in and through each other' (Butler 1993, 116-117; 1999 [1990], 18-19; 2004, 227-230).

[13] My reading of Butler's work is that she joins the postcolonial feminist critique and the recent intersectionality debate arguing for a contextualised analysis of normativity. The contesting of norms and normalising practices takes place in localized contexts, mundane everyday encounters with the norm. Localised analysis of normativity requires, however, understanding of the workings of gender in global contexts, in order to resist forms of universalism (Butler 2004, 9). Consequently, interconnections between postcolonial feminism, recent debates in queer studies and feminist engagement with the concept of 'intersectionality' provide an important insight for understanding the processes of normativity.

[14] First, postcolonial feminists and women of colour have long criticized how gender is made into a universal priority for feminism and offered the concept of intersectionality to understand the complexity of subject formation (Crenshaw 1991; Mohanty 1991; Phoenix and Pattynama 2006). Second, postcolonial studies have provided a more general critique towards the academic attempts to universalize analytical categories by reproducing a binary between tradition and modernity. In this binary, 'modern' usually refers to the Euro-American scholarship that promotes Western-based subject positions and forms of sexuality as global identities. "The western body stands as the normative body in scholarly discourse and in public policy" (Grewal and Kaplan 2001, 666, emphasis added), which Joseph Massad (2007) has called the 'internationalisation of western sexual ontology' (Massad 2007, 40). In fact, Rosi Braidotti, drawing on the work of Avtar Brah, calls the logic of advanced capitalism as "a difference engine" in which subjects are constituted in and by multiplicity, in the "intimate web of interconnections between race, gender, class and ethnicity" (Braidotti 2006, 67).

[15] In Butler's words, then:

It is not simply a matter of honoring the subject as a plurality of identifications, for these identifications are invariably imbricated in one another, the vehicle for one another...it is not a matter of relating race and sexuality and gender, as if they were fully separable axes of power; the pluralist theoretical separation of these terms as "categories" or indeed as "positions" is itself based on exclusionary operations that attribute a false uniformity to them and that serve the regulatory aims of the liberal state (Butler 1993, 116).

This suggestion to move towards multiplicities and complex differences resonates with the recent feminist criticism of the concept 'intersectionality', which is often conceptualised as an analysis of multiple 'axes of power' (Grabham 2009; Hancock 2007a; 2007b; Kantola and Nousiainen 2009; Puar 2005). Davina Cooper (2004) has summarized the problems of intersectionality into three key arguments: first, the axes metaphor produces bipolar positions: powerful and powerless. This forced polarity omits the possibility of being located "along a race/class/gender continuum, rather than at its polarity". Second, the axes approach seems to be unable to account for complex or unknowable ways in which social axes combine and at times contradict general assumptions: "what may seem a subordinated identity in one context, may amplify power in another" (Cooper 2004, 47). Finally, although groups are assumed to be constituted in relation to one another, axes are placed prior to the relations of experienced inequality (ibid). Cooper aligns with Butler's idea that categories, such as 'gender' and 'sexuality', do not exist before they are performed in a social context and established as norms. In fact, there is nothing natural in them. Rather, they are effects of social and political practices and discourses (Butler 1999 [1990], 10,34).

[16] Emily Grabham (2009) refers to intersectionality as the experience of social inequalities, as an expression of trauma, and the physicality of power relations that is intensely embodied on an individual level as emotions, physical encounters and intensifications of feelings (Grabham 2009, 196, 198). Grabham, reading Sara Ahmed's work on emotions, argues that "paying attention to the impressions that subjects make on one another can allow for a political reading of encounters that go beyond the individual subject and beyond the law's construction of individuals through disciplinary identities" (Grabham 2009, 198).

By investigating trauma as a mundane state of being, produced across physical and emotional encounters, it is possible to approach the complexity of inequalities without thereby contributing to the production of 'new' categories...it is possible to focus instead on how different histories of oppression converge through and across the way that people interact (Grabham 2009, 199).

This requires analytical sensitivity towards social inequalities, narrated through public encounters as claims of rights abuses, but also experienced in mundane ways as affect, emotions, and feelings: "through an account of how subjects experience enmeshed inequalities on the mundane, everyday level" (Grabham 2009, 194).

[17] Now how is one to read normativity and intersectionality in cultural productions, such as the radio drama in question and other gender advocacy materials? Normativity could also be called 'the cultural image-repertoire' that passes for a 'reality' that consists of representations that both enable and constrain how we perceive others and ourselves. In this essay I apply a 'close reading' method in order to locate the intersectionalities of norms and the subversion to the norm in policy documents and images. Sara Ahmed describes this process as:

reading which works against, rather than through, a text's own construction of itself (how the text 'asks to be read')..The disobedient reader...is a reader who interrupts the text with questions that demand a re-thinking of how it works, of how and why it works as it does, for whom (Ahmed 1998, 17).

This way of reading refers to a method that pays attention to details of texts and images, locating stability and continuity but also instabilities, differences, contradictions and exclusions (Koivunen 2003, 15). A close reading of the intersectionality of norms requires an understanding of the research data's wider socio-political context. It is through the context that the details begin to speak alongside the obvious 'given-to-be-seen' interpretations of the texts and images (Palin 2004; Vänskä 2006). The method of close reading requires patience with the displaced and unsaid signs that texts and visual images offer (Bal 1991, 411ft419). Even the smallest details can be read as signs that subvert the iconographic [5] coherence of the meaning (Palin 2004, 42). Once the focus is on the details, they become 'talkative and noisy', and can no longer be sidelined as unimportant (ibid, 46). The process of analysis includes a focus on impressions, feelings and aesthetics (Bleiker 2001; Grabham 2009; Shapiro 2009). Focusing on details allows sensitivity towards intersectionality of norms: what is the emerging picture of 'better' and at what consequences? What alternative stories exist that resist the dominant understandings of 'better'?

[18] The rest of this paper focuses on two readings of the 'Women Can Do It Too!' radio drama production. The first one focuses on the storyline, and the other focuses on the details and the not-spoken aspects of adolescence in Aceh.

Ida, the Embodiment of Better Future

[19] The radio drama is set in an anonymous tsunami-affected village in Aceh, and although not explicitly introduced that way, it is evident from the setting of the radio drama and the poster images that the characters have settled into their new (OI built) houses and throughout the episodes utilize the services of successful post-tsunami initiatives. However, although the wider setting is the village in general, it is the family of Umar, Pocut, grandmother, and children Ida and Adi, which takes the central role in introducing the key themes of the radio drama. Placing one family as the focus of the radio drama seems to be common in various other entertainment-educational dramas: 'a typical family' is located in 'a typical societal setting'. Internationally famous examples of this genre include the BBC production 'The Archers' which is considered as an archetype of radio dramas that are exported across the world in different variations: 'Cock crow at dawn' (Nigeria) and 'For Farmers' (Nigeria), 'Life in a Hopeful Village' (Jamaica), 'Happiness lives in small things' (India), and 'New Life, New Home' (Afghanistan) (See an analysis of the production of 'New Life, New Home' in Skuse 2005).

[20] The use of popular culture, such as radio drama productions, has become an important technology of the aid-and-development-planning governmentality (Hellman 2003; Pemberton 1994; Singhal and Rogers 1988; 1999; Storey 2000), and radio programmes have become an increasingly popular way of communicating about reconstruction and peace-process related issues in Aceh (see e.g.Tanesia 2008). Radio, of course, has a longer history of entanglement with ideas of development and modernity. For example, Franz Fanon has famously emphasized the role of the radio as a "technical instrument of colonialism, spokesperson of the colonial world" (Fanon 1965, 74), whereas Rudofl Mrázek has called Indies radio a "tool to define a modern colonial space" (Mrázek 1997, 9). Thus, radio could be argued to be a vehicle for constructing norms and ideals for the reconstructed Aceh.

[21] Radio Flamboyant, the producer of the radio drama, advertises itself as a "hit music station" [6]. It has its audience in the upper middle class of urban Banda Acehnese adolescents and young adults (16 – 30 years old audience). The post-production focus group participants in 2007 complained that the image portrayed of the village was not accurate, and the characters used language that was too urban to construct a convincing narrative of Acehnese village life (Info Aceh 2007, 13). Thus, it could be argued that the radio drama production constructs the Acehnese village life through urban lenses, reiterating a stereotypical image of the rural Aceh as backward and in need of development.

[22] The storyline of the radio drama is introduced in the following way: the listeners enter and exit the 'world of drama' in each episode with the help of the title music and a narrator. The punch lines are repeated by the narrator several times during one episode: as an introduction for each episode and at the end of each episode as a revision. The narrator plays an important role in framing the storyline of each episode. The repeated narrative establishes a normative framework or 'cultural repertoire' within which each episode should be understood or listened to. The voice of the narrator is the normative voice of the production team who

decides what is inside and outside the narrative world, which is also, implicitly, a decision about what is inside or outside a world whose language tries to normalize some behaviours at the expense of others (Bruhm and Hurley 2004, x).

The storyline of the radio drama production focuses on promotion of gender equality through women's rights. The themes include a girl child's right to higher education; women's voices in public matters (freedom of opinion); women's voices within the family and village-based decision-making; women's economic situation (livelihoods); women candidates in local elections; women's land rights/inheritance; reproductive rights; guardianship rights; sharing household duties; and the issue of marriageable age. These 'women's rights' focused topics resonate with both the gender documents of the Beijing Conference and major gender and Islam policy documents produced by both the Indonesian central and Acehnese provincial governments.

[23] Although different episodes take different characters of the radio drama as their focus, there are two characters whose transformations are significant: Ida, and her father Umar. Ida is the focus of both the first and the last episodes (which concentrate on the issue of Ida's future). I argue that one of the key normative messages provided in the radio drama relates to constructs of normative time and space: the right timing of events in adolescent girls' life guarantees better futures. Whereas Ida is portrayed as the 'future', Ida's father Umar on the other hand is portrayed as patriarchal, traditional, and being initially against fulfilment of women's rights in his family, but then, as to reach a happy ending for each episode, he changes his position. Claire Colebrook has argued that "girl...functions as a way of thinking woman, not as a complementary being, but as the instability that surrounds any being" (Colebrook 2000, 2). The storyline thus creates a radical relation to Umar: "not as his other or opposite (woman), but as the why becoming of man's other" (ibid).

[24] The normative narrative of 'better' is supported with binary positions and dichotomies such as backwardness-empowerment/progress, passive-active, lazy-productive and so on. These binaries are constructed primarily with the relationship between Ida and her father Umar, but in general the ones who are for gender equality, and those who are against it. This is a common feature for melodramas, which, according to Pamela Brook, reaffirm social rules and champion "romanticized ideas of heroes and heroines" (Brooke 1995, 41). An important part of the promotion of positive behaviour and attitudinal change is that the audience is able to identify with the leading characters and that the desired behavioural patterns are indicated as clashes between the good and the bad characters (ibid). However, as I will later illustrate, instead of taking the storyline as a fixed and stable set of normative images, the radio drama production is treated as a "positive repetition" that inhabits the dominant discourse of transformation in order to open up new sites of social critique (Colebrook 2000, 7).

* * * * * *

[25] Episode 1, "Ida Too wants to continue her education," is introduced by the narrator as follows:

"This episode is about opinions in our society, according to which women do not need higher education because after marriage they will only work in the kitchen and manage the household. Although, all people have a right to education. Is this opinion still common? And how far are women's attempts at the moment to gain education? Let's listen carefully to the drama..."

The first episode starts with a dialogue at Ida's school, where the teacher reminds the class of the approaching national examinations. Ida returns home and to her great disappointment, she hears that her father does not support the idea. Instead, he is happy that Ida will finish school soon:

Umar: Wah, that is good news. Shortly Ida has completed her schooling and mother will have someone who will help her at home

Pocut: Wah, that is also true, Pak

Ida: But actually, my teacher suggested that I should continue classes...

Umar: Allah...why do you want to continue studies! Just look at Midah, Akob's child. She finished her classes and does not have work.

Grandma: Who knows, perhaps Ida is smart?

Umar: Allah, don't talk like that

Ida: But father...

Umar: Hmm...remember, you are my daughter, why does a girl need higher education? Later after the wedding, you're going to be at home, taking care of your husband. What is important at the moment is that you study how to become a good wife. That's what is important now. [7]

During the teacher's visit to the house, Ida's father, Umar, tries to raise his concerns about the family economics, by saying: "we do not have rice field that we could sell or put in mortgage". However, the issue is quickly resolved by the teacher, who confirms, that if Ida works hard enough, she will surely get a scholarship. [8] Ida's father's points out the family's economic problems, and further, the high unemployment rates for those with higher education degree in Aceh, which are both dismissed. Later in the episode, after persuasion by Ida's teacher, mother and grandmother, Ida gets the permission from her father to continue her education and starts taking the first steps towards her dream: to become a doctor.

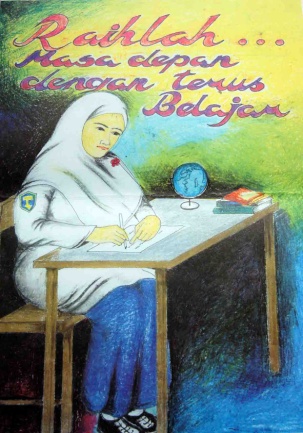

[26] Several posters produced to advertise the drama illustrate the punch line of this episode: rights are attainable with hard work and a change of attitudes on the part of society. For example, the poster that was used to advertise the first episode shows a girl in school uniform, studying, with the caption "Achieve it... a future with continuing Education".

Poster 1. "Achieve it...Future with Continuing Studies". Oxfam International.

[27] The globe on the table could be interpreted as introducing the idea of the global focus on girls' education, which is not only an Acehnese standard, but in fact, a standard for the whole globe (United Nations 2001; 2008). In Sara Ahmed's words, "the life course of the girl becomes a metaphor for the life course of 'the globe' itself. In this way, the fulfilment of the girl's potential marks the course or trajectory of the globalisation of feminism" (Ahmed 2000, 175-176). [9]

[28] In fact, the focus on the promotion of girls' schooling is nothing new, but rather, has been part of both Dutch colonial policies and Indonesian decolonisation and nation-building discourses – and in fact forms an important part of the idea of modernity and Indonesian nationalist struggles against colonialism. In fact, the first Women's Congress held in 1928 paid particular attention to the questions of the girl child's education and early marriage. Susan Blackburn's analysis of pre-independence Indonesia suggests that nationalist movements opposing colonialism wanted schooling to promote commitment to national unity and independence and help mould skilled citizens capable of constructing a strong modern society (Blackburn 2004, 33); however, with gendered and sexualised undertones: the idea of education revolves around the girl's responsibility of raising the next generation of Indonesian citizens.

[29] The episode creates an impression that education is available equally for all, once the gender norms of the society, i.e. the father's patriarchal and misogynist opinions, are changed and the individual works hard enough. The discourse of the individual's responsibility to work hard can also be found in the magazine 'Voice of Women' (Suara An'Nisa), published by the provincial office of the Bureau for Women's Empowerment. The March 2008 issue contained aphorisms like: 'winners make things happen, losers merely wait for it to happen' and 'winners have time to think, losers are lazy to think', and 'winners follow the winners, losers follow the losers' (Badan Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak 2008, 4,13). In fact, at the end of the first episode, once he has agreed to support the further education of her daughter, Umar reminds Ida that she first has to be 'diligent' and prepare herself for the national examinations. Ida replies: "I promise, I will study and will not disappoint you". The father has been transformed, from patriarch to result-oriented and demanding father. Umar's transformation resonates with the wider liberal economic policy rhetoric of equal opportunity and individual attainment: "poverty can be eradicated through the entrepreneurship and hard work undertaken by the disadvantaged individual" (Isserles 2003, 43), ideals that are repeated elsewhere in the radio drama through narratives of women's livelihoods groups and small businesses.

[30] The portrayal of Ida's future provides a normative conceptualisation of time and space: the right timing of events in an adolescent girl's life guarantees her a better future. By normative time and space I refer to the idea that cultural representations portray certain phases of life (time, such as marriageable age), and certain places (space, such as school or family) as normal. Arja Mäkinen calls this the 'social watch/calendar' or 'norms that govern phases of life' (Mäkinen 2008, 33). Accordingly, normative time appears also as the normalised rhythm of daily life, and the life cycle. [10] The radio drama establishes several normative narratives of the rhythm of adolescent girls' lives: attending school; preparing for the national examinations; finishing school first and only then getting married; having two children. Ultimately, adolescent girls are seen as future mothers who have an employment outside of home (Muhammad 2002, 3).

[31] Bruhm and Hurley have argued that projecting children into a heteronormative future relies on an assumption that childhood is essentially heterosexually determined and implicitly increases "the pressure on producing the proper ending of the story" (Bruhm and Hurley 2004, xiv).

"The last week's episode narrated about a husband who left his house because he could not cope with listening his baby's cry at night. Well, this time is the time of the last episode, which will narrate about Ida who is proposed. Well, what is the reaction of Ida and whether Ida is successful in getting married?" (Narrator in the episode 12, "No Marriage for Ida")

In the last episode Amin, who lives in the provincial capital Banda Aceh and has a permanent job and good socio-economic status, proposes marriage to Ida through Ida's parents. Ida refuses to get married, as she wants to first study to become a doctor. The episode continues with a dialogue between Pocut, Umar and their daughter Ida, which leads to the conclusion that Ida does not want to get married before she has finished her studies – not that there is anything wrong with the candidate, but the timing is not right. The episode ends with a dialogue between Ida and her older friend Tuti at Tuti's wedding ceremony where Ida narrates the events of that day to the bride.

Tuti: ... [your situation] is just like mine was earlier: I was asked to get married but I did not want to because I wanted to finish my school first. Now that I have finished it and already have a job, now I can get married. It is important that we study hard first. Perhaps you can also become a doctor.

Ida: Oh, this means that we are the same, sister. I also want to become a doctor first, then later think about getting married. Isn't it true sister?

The last episode provides several subversions of the norm: first, a common narrative in popular culture (TV soap operas, movies) is of the rural bright girl lifting her socio-economic status by marrying a stable and wealthy man (Singhal and Rogers 1988, 111). Second, parents are portrayed as modern parents who listen to their children's concerns. Third, the drama plays with the idea of Ida's relation to family life and sexuality. The ending of the radio drama leaves Ida's future open, and this can be seen as a subversion of the otherwise naturalised assumption of heterosexuality. However, it does play along with the dominant norm, according to which it is "indisputable that everyone is sexual" (Pollard 1993, 108).

[32] Several queer theory scholars have focused on the discursive connections between heteronormativity and future, adolescence and gender, sexuality and citizenship, which Lee Edelman has called 'reproductive futurism' (Edelman 2004, 27). Laurent Berlant (1995; 1997) argues that that a girl child stands as a "condensation of many citizenship fantasies" (Berlant 1995, 380; 1997, 58). "Utopianism follows the child around like a family pet. The child exists as a site of almost limitless potential (its future not yet written and therefore unblemished)" (Bruhm and Hurley 2004, xiii). However, "the utopian fantasy is the property of adults, not necessarily of children" (ibid, xiii).

[33] A closer look at the radio drama storyline confirms these fantasies: it is one of the campaigns that Oxfam International had specifically targeted at the young adults, namely 15-24 year olds. Despite the centrality of Ida as an adolescent girl, the adolescent girl's world is constructed through the eyes of adults. In essence, Ida's story is an adult fantasy narrated to Acehnese youth. Fantasies about the adolescent girl's futures have intertextual connections with other gender advocacy materials. Sara Ahmed's analysis of the Beijing Conference final document illustrates that a significant relationship is constructed between the 'girl' and the 'future woman' in the Beijing outcome document: growing from a girl into a woman becomes a measure of 'global development', a move from underdevelopment to development. The life course of a girl child becomes a wider metaphor for the progress of the 'globe' (Ahmed 2000, 176).

[34] In the case of the radio drama, the girl child becomes the indicator of the progress of the tsunami reconstruction in Aceh. Idea of progress is manifest in the radio drama by Ida's ambition to become a doctor. Images of the female body are used to signify the transition from tradition to modernity. Female bodies act as indicators of modernity of the nation, illustrated with qualitative and quantitative 'gender sensitive' indicators. The narrative of the future of the girl child coincides with the idea of 'new generation' that refers implicitly to the language of heterosexuality and to "the importance of the heterosexual couple to the international community" (Ibid). The normative story of the female body therefore is that it makes the transformation from a girl to a woman, from a child body to an adult body.

[35] Leaving the future of Ida open, the radio drama provides a subversive site to other narratives of adolescence that are marked with heteronormative indicators: reproductive maturity (menstruation) and marriageable age (Parker 2008, 393). [11] Adolescence is an essential part of the state-building discourse and Suzie Handajani argues that the marriage law and nine years of compulsory education (between six and fifteen years of age) have further embedded the concept of 'adolescence' in the Indonesian state discourse (Handajani 2008, 93). When the word remaja [12] appeared within the New Order [13] discourse to describe the 'future generation', a contradiction emerged. The government discourse strongly emphasised the need to protect the young generation from the bad influences of globalisation, yet recognizing that youth provides a growing market base (ibid 2008, 130). Berlant has pointed out that the specific focus on the morality of a girl child signifies the state's fragility. The constant anxiety over whether people conform to the state ideals that form the national culture illustrates how states are in a constant process of making. Biological reproduction provides ways to visualise the national future and the vision is often embodied as girl children (Berlant 1997, 56). [14]

[36] A closer look at the government documentation on adolescence reveals the moral concerns posited towards adolescence. The Mid-Term Development Plan of the Aceh government for 2007-2012 locates the youth as a measure of progress. Adolescence is constructed as an indicator of the 'success and degradation of a nation' and 'an agent of transformation' (Gubernur Provinsi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam 2007, II-37). The potentiality of youth is recognised, but the analysis puts specific emphasis on the risks and threats that await the new generation, such as "unemployment, moral decadence, free sex, use of narcotics and criminality" (ibid, II-38). The Acehnese development plan turns these 'social ills' into a development agenda where the youth will be empowered so that they can "make a solid contribution towards the society, nation and the state" (ibid, II-39). The plan admits, however, that both the conflict and the natural disaster have caused a decline in the productivity and role of youth in development activities, and thus a long physical and mental rehabilitation and reconstruction is needed (ibid). What is remarkable about this framing is that the impacts of the conflict and the tsunami are described as a decline in productivity, not as a question of wellbeing. The focus on youth is instrumentalised and seen only as significant for economic development, not necessarily as a concern about the wellbeing of the youth as such.

[37] Another layer of the normativity of adolescence becomes visible while reading the radio drama production alongside the booklet 'Adolescent Girl on the Edge of Loving and Compassionate Life' [15], published by the Bureau for Women's Empowerment. The booklet (Muhammad 2002) claims that it is the responsibility of adolescent girls to control the impact of foreign culture (arriving from the West) that challenges Islamic thinking in Aceh. [16] Religious education is suggested as a means to ensure that adolescent girls are able to control the negative impacts of the globalisation (ibid, 8-9). This attention, based on a reading of the booklet, involves clearly set normative boundaries of what constitutes morally good behaviour for girls, aligning with the official lines of the formalisation of Shari'a law: focus on morality and codification of norms on 'proper Muslim behaviour'.

[38] It is remarkable, given the context, that the radio drama portrays religion merely as an issue of worship and individual's responsibility: no references are made to the religious authorities or the formalised Shari'a law. The analysis normalises and depoliticizes the discussion on Shari'a Islam in Aceh. The radio drama setting constructs women as religious and pious and the posters focus on getting women's Muslim dress 'right' vis-à-vis the dominant Shari'a Islam discourse. Thus the radio drama production replicates the current focus on women's behaviour and bodies through 'jilbab razias' that focuses exclusively on arresting women who are not properly dressed. The normative consequence of these portrayals (religion as individual responsibility; gendered constructs of 'proper Muslim dress') is that gender advocacy silences the politicized nature of the implementation of Shari'a law. Furthermore, as Aceh is presented as 100% Muslim, the existence of religious minorities and their special concerns in relation to the implementation of Shari'a law are omitted from the narrative.

[39] It seems that the expectations of the progress and development of the nation and of the global feminist agenda become embodied in a female Muslim body. Ida's character clearly provides the possibility of reflecting differently the norms governing adolescent girls: framing adolescence in the language of empowerment and progress, as a positive indicator for the overall development and progress, and subverting the existing norms that govern the lives of adolescent girls in general. Yet, as illustrated in the above examples, this construct also produces some problematic connotations: female bodies become part of the nation-building discourse in which humans are seen as assets and means for national development and defined from the perspective of economy, religious piety, and biological reproduction.

[40] One way to conclude the openness of Ida's future would be that it offers a queer ending for a storyline that is otherwise embedded in the heteronormative framework of family, reproduction and citizenship. One could celebrate the story of Ida as a resistance to gendered and sexualised images of adolescence. Furthermore, the storyline actively subverts the persistent stereotype of tsunami survivors as passive victims who need to be helped. Compared with the images of suffering produced in the aftermath of the tsunami (Childs 2006), the posters and the radio drama challenge at least two discourses: first, the prevalent 'disaster discourse' in which particularly women, particularly, are portrayed as helpless victims who are passive and in need of help (ibid.). Second, they undermine the discourse that portrays women living under Islamic law as oppressed and passive victims, what Lila Abu-Lughod has described as "white women [are] saving brown women from brown men" (Abu-Lughod 1998, 14). I remain troubled, however, as to whether this discursive shift from 'passive victim' to 'active agent of change' can be celebrated so easily as it appears that the same discursive change is part of the disaster management cycle of normativity: images of suffering are produced right after the disaster during the disaster relief phase whereas the reconstruction and focus on longer term development goes hand in hand with images of improvement and happiness. Recovery aid narratives are often justified on the grounds of narratives of suffering and vulnerability (Edkins 2000) and portrayed together with images of passivity and distress (Childs 2006, 208). The logic of disaster imagery, as Laura Briggs has argued, constructs a universalized 'way of seeing' the disaster contexts: the suffering that is described in the aftermath of a disaster transforms into narratives of progress and development in linear fashion (Briggs 2003, 179).

[41] Aligning with Sara Ahmed's (2010) critical analysis of constructed happiness, the following section illustrates that the analysis solely focusing on the storyline, i.e. promotion of gender equality and positive transformation from tsunami experiences to better futures, falls short. It suggests, using examples from Aceh, that the images of adolescent girl are entangled with other social hierarchies and encounters with the tsunami and the conflict, gaining meanings in the locally lived experiences of adolescent girls that further provide a critique towards simplistic images of adolescence.

Multiplicity of Encounters with Adolescence

[42] Kimberly Hutchings' notion that a critical postcolonial and feminist understanding of time could offer possibilities to question the universalistic assumption that "all women occupy the same time" or to refuse to "read temporal plurality in normatively hierarchical terms" (Hutchings 2007, 85). Further, queer studies has shown how normative images are not only articulated through notions of sex, gender and sexuality, but also how they relate to wider aspects such as temporalities, life-schedules and economic practices (Halberstam 2005, 1). Conceptualizing temporality as multiple gives us the possibility of remaining cautious of "unwarranted and dangerous assumptions about both the unified nature of the future and our capacity to know it" (Hutchings 2007, 89). Hutchings continues: "accounts of temporal patterns of clock time...are dangerous because they distract attention from political plurality, and thereby risk repeating the hubris of Western political imaginaries" (ibid).

[43] If the official post-tsunami reconstruction and gender mainstreaming discourse portrays dominantly an image of progressive chronological temporality, it is not to say that no other alternative notions of temporality and spatiality exist. By focusing on the norms, and the consequences of such norms, Butler suggests that it is the cracks and ruptures in the norms that form a basis for emerging agency and potentiality for feminist politics. Cracks in the seemingly consistent system of normativity create new possibilities for expressions of livable life, possibilities that challenge normative violence, heteronormative structures, and assumptions of kinship (Chambers and Carver 2008, 129,134). Cracks in the context of Aceh, have a very specific connotation: cracks in any (re)constructed spaces in Aceh are an evidence of constantly reoccurring earthquakes, phenomena that is unexpected and unpredictable. [17]

[44] Although the radio drama is clearly a product and reproduction of hegemonic heteronormative culture and norms (ibid, 188), the 'out of place' feel to the final broadcast production allows one to see norms denaturalised and recontextualised – as a parody. The "parodic repetition of the 'original'...reveals the original to be nothing other than a parody of the idea of the natural and the original" (Butler 1999 [1990], 43). Parody to Butler offers possibilities: "the perpetual displacement constitutes a fluidity of identities that suggests an openness to resignification and recontextualization" (ibid).

[45] Drawing on Jean-François Lyotard's work on 'political posters', [18] I argue that there is a relationship between the explicitly normative story-line, the 'organisation of society', and the 'plastic surface' of the posters: a relationship between 'plastic space' and 'textual space' (Lyotard 1985, 211), or discursive space and visual space. Lyotard argues that without the text, the figures in their silence and immobility would torment the spectator: "the text is the order...reassuring image which one recites to oneself – an image into which I can resolutely project myself" (Ibid, 214). The textual space conforms to the main plots of the radio drama, each poster repeating the particular women's rights that the production aims to advocate. This 'plastic space' of the posters offers possibilities for multiple readings, challenging "the assumption that there is a direct relationship between the visible and the real" (Campbell 2009, 54).

[46] The child-like, simple and na?vely styled posters use juxtaposed primary colours and in so doing offer a subversive space away from the story-line of the radio drama production. What is known as 'naïve art' or 'raw art', either looked down on by high art critics, or considered not subversive enough by theorists, deserves a closer reading as a potential subversive space. The Encyclopaedia Britannica describes the naïve art as "work of artists in sophisticated societies who lack or reject conventional expertise in the representation or depiction of real objects", which allows for a narrative of playfulness (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008).

[47] The posters portray people with smiles on their faces. Sara Ahmed (2007b) holds that "happiness functions as promise, which directs us towards certain objects, which then circulate as social goods" (Ahmed 2007b, 123). Laurent Berlant has called the fantasy of happiness a 'stupid' form of optimism: "the faith that adjusted to certain forms of practices of living and thinking will secure one's happiness" (Berlant 2004, quoted in Ahmed 2007a, 10).

It is the very assumption that good feelings are open and bad feelings are closed that allows historical forms of injustice to disappear. The demand for happiness is what makes those histories disappear...these histories have not gone: we would be letting go of that which persists in the present, a letting go which would keep those histories present (Ahmed 2007b, 135).

Indonesian art critic and feminist scholar Carla Bienboen remarks that a closer look at the atmosphere of familial happiness and intense child-like joy could also reveal well-hidden pain: "the vibrant colours reflect optimistic expectations and wishful thinking rather than reality" (Bienpoen 2001). [19] Thus, I argue, the use of motionless figures with their childlike smiles could be seen at the same time as playful, but also haunting, in search of happiness and joyfulness. "The violence is in the knowing...not directly in seeing" (Santu MofokengHayes 2009, 37).

[48] A subversive reading of the posters and the drama characters questions the naturalness of seeing the characters as 'men' and 'women' or the natural alliance between 'sex' and 'gender': feminine referring to female and masculine to male. Judith Butler's critique of the stability of sex and gender releases the characters from these assumptions; what appears to be male and female are simply dresses and acting that reiterate the binary of male/female (see also Jauhola 2010). When gender is released ontologically, i.e. when the concept of gender no longer rests on the binary of man/woman, Butler reiterates, it becomes impossible to discriminate between right and wrong genders, sexes or directions of sexual desire, as there is no longer a model against which to judge any of 'their myriad expressions'. Once gender is not dependent on sex, it becomes an 'act', a daily performance that constitutes identity. "No one can be said to have a gender anymore; it is not a possession, nor it is something that one simply is" (Butler 1992 [1989], 260-261). This further allows the analysis to conclude that the normative boundaries of the radio drama production are a result of a selective reading of the production and an unnecessarily limited reading of the representations the radio production could offer. Thus, the images portrayed in the radio drama production should be treated as a construct of Acehnese adolescence, not a replica or 'true descriptions' of reality.

[49] Furthermore, the claim that the (gender) inequality in education is "largely driven by the (false) self-interests of...men...ignores the ways in which other aspects of the social shape and influence gender relations" (Cooper 2004, 50). According to this view, gender inequality is solvable through attitudinal change rather than focusing on other social or structural processes (ibid). In fact, a closer analysis of the social inequalities of the education system in Aceh demonstrates that an analysis that focuses solely on gender inequalities or patriarchal attitudes does not 'capture' the totality of challenges of the inequalities that Acehnese people face in accessing education or how gender norms intersects with other social differentiations. The sole focus on the father's 'patriarchal values' masks several other important factors that hinder access to education in Aceh. The tertiary enrolment in Indonesia was 17 per cent in 2006 (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2008) and in Aceh the figure in 2003 was under 9 per cent, university education under 6 per cent (Presiden Republik Indonesia 2005). Attendance in higher education in Aceh is overrepresented by male and female students from urban areas, rich households and Acehnese ethnicity. Thus differentiation is not only based on gender, but also ethnicity and geography, economic situation and distinction between rural-urban. Amongst those are, further, the context of the conflict, economic situations and urban-rural divide, quality and relevance of education, access to formal employment, and tsunami corruption, the fact that not all tsunami affected children have benefited equally from the tsunami aid. I only address here two of the immediate ones that are vocally expressed in my wider fieldwork in Aceh between 2006 and 2009.

[50] The thirty year long conflict, especially in the high conflict areas of northern coastal Aceh that were affected by the tsunami, has left behind several generations of Acehnese who have not managed to complete their education due to the conflict. Usually primary and middle schools are within a short distance from one's village; however, in some cases high school can be located as far as 40 kilometres away in the capital of the sub-district. During the conflict (until August 2005) both the Indonesian military and the GAM were regularly stopping children, particularly boys, suspecting them of providing intelligence for the other party. Also, "the problem of schooling goes back to the issue of ID cards" (interview, 6 September 2007a). State-led education is restricted to children with ID cards: to obtain an ID card, the applicant has to provide a birth certificate and marriage certificate of the parents. This automatically leaves out those who either did not have an ID card because they were suspected of being sympathetic to the GAM, or those who were born out of informal relationships.

[51] Further, to illustrate the difficulties of schooling in the post-tsunami context in Aceh, Banda-Aceh based film-making students produced a short-documentary titled 'The Odyssey of Rani Monika' in 2008 (Kamila and Sugesty 2008). The documentary portrays the long daily labi-labi (minibus) journey of Rani Monika, who lives in a barrack with her parents far away from her school. Rani's narrative unfolds other stories of unfinished tsunami reconstruction process: promises of houses that were never built, and educational scholarships that have gone missing. OI's report 'Women evaluate the Tsunami Response' indicated that some heads of schools manipulated the data to distribute scholarships to their preferred students, and some students received more than one scholarship (Oxfam 2008). Similarly, while staying in Aceh, I came across several narrations of various other life worlds for adolescent girls, which illustrate how the picture of Ida is highly idealized and uncritical and leaves the gender analysis unfinished. I was told of villages that had no adolescent girls as they had all migrated or been trafficked to urban areas (predominantly in Aceh or in Malaysia) as domestic workers, sometimes to work in the houses of the international and Acehnese aid workers, and how, often, university students were financing their studies through prostitution.

[52] The storyline of 'progress' and 'better future' would not be complete if the visual detail of the posters, the fair skin colour of the characters, is not incorporated into the analysis. All characters are portrayed as fair-skinned, in line with the existing beauty norm widely available in women's magazines and TV programmes. There is a lot of advertising for whitening powder and cream, which areavailable in Acehnese shops and used amongst the urban middle-class, not just by adults, but also for small babies, females and males alike. This idealization of colour with progress and empowerment is what Sara Ahmed has described as the 'phenomenology of whiteness': an effect of racialization, which shapes and orients how bodies 'take up' space and what bodies can do (Ahmed 2007c, 150). The idealisation of whiteness adds a troubling dimension to the normative message of the gender advocacy campaign, positioning whiteness "as a background to experience" (ibid) and an indicator of progress and development. This takes the storyline of the radio drama back to the centre of the women of colour and post-colonial feminist critique: production of white skin and white embodied experience as an ideal and the indicator of progress. The 'fair complexed' bodies on the posters "are a reminder of the histories of colonialism, which makes the world 'white', a world that is inherited, or which is already given before the point of an individual's arrival" (ibid, 153).

Conclusions

[53] This article had two main aims. First, to provide a theoretical framework for the analysis of the intersectionality of norms. It suggested that normativity could be understood as a constant process of negotiation of intersecting norms, not necessarily constructed as exclusions and opposition between self and the other, but rather, as a process of multiple becomings, and intersubjectivity.

[54] Second, this article introduced Ida and "Women Can Do It Too!" The storyline reiterates the significance of a heterosexual adolescent girl as the signifier of the success of the tsunami reconstruction process, the progress of the nation, and ultimately, the progress of the globe and global feminism. By leaving the future of Ida open, the production offers avenues to resist simplistic gendered and sexualised categorisations of adolescence outside the heteronormative frame. However, the article suggested that this opening is entangled with other social hierarchies, such as ethnicity and encounters with tsunami and conflict that gain meanings in the locally lived experiences of adolescent girls, and thus the radio drama provides a more complex critique of the normative negotiation of adolescence in Aceh.

[55] The article suggested that a close reading of the radio drama production offers a critique to the seemingly stable and closed gender advocacy storyline offered by the narrator of the drama and that adolescence could be considered as an embodied process of constant negotiation of norms. A conscious subversive reading offers the possibility to treat the radio drama production as performative politics: a parody, with sarcastic, but also at times tragic and unsettling undertones.

Bibliography

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 1998. "Introduction: Feminist Longings and Postcolonial Conditions." In Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East, ed. Lila Abu-Lughod. Princeton: Princeton University Press,3-32.

Agency for the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction for Aceh and Nias. 2006. "Policy and Strategy Paper: Promoting Gender Equality in the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Process of Aceh and Nias." Bureau of Rehabilitation and Reconstruction for Aceh and Nias, September 2006.

Ahmed, Sara. 1998. Difference that Matter: Feminist Theory and Postmodernism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ahmed, Sara. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London: Routledge.

Ahmed, Sara. 2007a. "The Happiness Turn." New Foundations 63(Winter 2007):7-14.

Ahmed, Sara. 2007b. "Multiculturalism and the Promise of Happiness." New Foundations 63(Winter 2007):121-137.

Ahmed, Sara. 2007c. "A phenomenology of whiteness." Feminist Theory 8(2):149-168.

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. London: Duke University Press.

Badan Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak. 2008. "Suara An-Nisa: Pemberdayaan, Kesetaraan, Persatuan dan Pengbdian [Women's Voice: Empowerment, Equality, Unity and Devotion]. Edisi Maret 2008."

Bal, Mieke. 1991. Reading "Rembrant". Beyond the World Image Opposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bell, Vikki. 2006. "Performative Knowledge." Theory, Culture & Society 23(2-3):214-217.

Berlant, Laurent. 1995. "Live Sex Acts (Parental Advisory: Explicit Material)." Feminist Studies 21(2):379-404.

Berlant, Laurent. 1997. The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bienpoen, Carla. 2001. "Erica Hestu Wahyuni in Retrospect." Indonesian Observer 14 April 2001. «http://www.javafred.net/rd_cb_4.htm». Accessed January 3, 2011.

Blackburn, Susan. 2004. Women and the State in Modern Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blackburn, Susan. 2007. "Kongres Perempuan Pertama Tinjauan Ulang [Review of the First Women's Congress]." In Kongres Perempuan Pertama: Tinjauan Ulang [First Women's Congress: Review], ed. Susan Blackburn. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia, KITLV-Jakarta,xviii-li.

Bleiker, Roland. 2001. "The Aesthetic Turn in International Political Theory." Millenium: Journal of International Studies 30(3):509-533.

Braidotti, Rosi. 2006. Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Briggs, Laura. 2003. "Mother, Child, Race, Nation: The Visual Iconography of Rescue and the Politics of Transnational and Transracial Adoption." Gender & History 15(2):179-200.

Brooke, Pamela. 1995. Communicating through story characters: radio social drama. Boston: University Press of America.

Bruhm, Steven and Natasha Hurley. 2004. "Curiouser: On the Queerness of Children." In Curiouser: On the Queerness of Children, eds. Steven Bruhm and Natasha Hurley. London: University of Minnesota Press,ix-xxxviii.

Butler, Judith. 1992 [1989]. "Gendering the Body: Beauvoir's Philosophical Contribution." In Women, Knowledge and Reality: Explorations in Feminist Philosophy, eds. Ann Garry and Marilyn Pearsall. London: Routledge,253-262.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. London: Routledge.

Butler, Judith. 1997. "Imitation and Gender Insubordination." In The Second Wave: A Reader in Feminist Theory, ed. Linda Nicholson. London: Routledge,300-315.

Butler, Judith. 1999 [1990]. Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Butler, Judith. 2004. Undoing Gender. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Campbell, David. 2009. ""Black Skin and Blood": Documentary Photography and Santu Mofokeng's Critique of the Visualization of Apartheid South Africa." History and Theory 48(4):52-58.

Carver, Terrell and Samuel A. Chambers. 2007. "Kinship Trouble: Antigone's Claim and the Politics of Heteronormativity." Politics & Gender 3(4):427-499.

Chambers, Samuel A. 2007. "'An Incalculable Effect:' Subversions of Heteronormativity." Political Studies 55(3):656-679.

Chambers, Samuel A. 2009. "A Queer Politics of the Democratic Miscount." borderlands e-journal 8(2):1-23.

Chambers, Samuel A. and Terrell Carver. 2008. Judith Butler and Political Theory: Troubling Politics. Oxon: Routledge.

Childs, Merilyn. 2006. "Not through women's eyes: photo-essays and the construction of a gendered tsunami disaster." Disaster Prevention and Management 15(1):202-212.

Cohen, Jeffrey J. and Todd R. Ramlow. 2006. "Pink Vectors of Deleuze: Queer Theory and Inhumanism." Rhizomes 11/12(Fall 2005/Spring 2006. «http://www.rhizomes.net/issue11/cohenramlow.html». Accessed January 2010.

Colebrook, Claire. 2000. "Introduction." In Deleuze and Feminist Theory, eds. Ian Buchanan and Claire Colebrook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,1-17.

Colebrook, Claire. 2008. "How Queer Can You Go? Theory, Normality and Normativity." In Queering Non/Human, eds. Noreen Giffney and Myra J. Hird. Hampshire: Ashgate,17-34.

Colebrook, Claire. 2009. "On the Very Possibility of Queer Theory." In Deleuze and Queer Theory, eds. Chrysanthi Nigianni and Merl Storr. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,11-23.

Cooper, Davina. 2004. Challenging Diversity: Rethinking Equality and the Value of Difference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color." Stanford Law Review 43(6):1241-1299.

Desai, Manisha. 2005. "Transnationalism: the face of feminist politics post-Beijing." International Social Science Journal 57(184):319-330.

Edelman, Lee. 2004. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press.

Edkins, Jenny. 2000. Whose Hunger? Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. "Encyclopaedia Britannica online academic version."

Eyben, Rosalind. n.d. "What is happening to donor support for women's rights?" Contestations: dialogues on women's empowerment, Issue 4. «http://www.contestations.net/issues/issue-4/what-is-happening-to-donor-support-for-women%E2%80%99s-rights/». Accessed April 2011).

Fanon, Franz. 1965. A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press.

Fraser, Nancy. 1995. "False Antitheses: A Response to Seyla Benhabib and Judith Butler." In Feminist Contentions: A Philosophical Exchange, eds. Seyla Benhabib, Judith Butler, Drucilla Cornell and Nancy Fraser. London: Routledge,59-74.

Grabham, Emily. 2009. "Intersectionality: Traumatic Impressions." In Intersectionality and Beyond: Law, Power, and the Politics of Location, eds. Emily Grabham, Davina Cooper, Jane Krishnadas and Didi Herman. Oxon: Routledge-Cavendish,183-201.

Grewal, Inderpal and Caren Kaplan. 2001. "Global Identities: Theorizing Transnational Studies of Sexuality." GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 7(4):663-679.

Gubernur Provinsi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam. 2007. "Peraturan Gubernur NAD nomor 21 tahun 2007 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Mengunah Provinsi NAD 2007-2012."

Halberstam, Judith. 2005. In a Queer Time & Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. London: New York University Press.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2007a. "Intersectionality as a Normative and Empirical Paradigm." Politics & Gender 3(2):248-254.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2007b. "When Multiplication Doesn't Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm." Perspectives on Politics 5(1):63-79.

Handajani, Suzie. 2008. "Western Inscriptions on Indonesian Bodies: Representations of Adolsecents in Indonesian Female Teen Magazines." Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 18 (October 2008).

Hayes, Patricia. 2009. "Santu Mofokeng, Photographs: "The Violence is in the Knowing"." History and Theory 48(4):34-51.

Hellman, Jörgen. 2003. Performing the Nation: Cultural Politics in New Order Indonesia. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Hickey-Moody, Anna and Mary Lou Rasmussen. 2009. "The Sexed Subject in-between Deleuze and Butler." In Deleuze and Queer Theory, eds. Chrysanthi Nigianni and Merl Storr. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,37-53.

Hutchings, Kimberly. 2007. "Happy Anniversary! Time and Critique in International Relations Theory." Review of International Studies 33(1-2):71-89.

Info Aceh. 2007. "Report [post-production assessment of the radio drama, unpublished report]."

Isserles, Robin G. 2003. "Microcredit: The Rethoric of Empowerment, the Reality of "Development as Usual"." Women's Studies Quarterly 31(3-4):38-57.

Jackson, Alecia Youngblood. 2004. "Performativity Identified." Qualitative Inquiry 10(5):673-690.

Jauhola, Marjaana. 2010. "Building Back Better? – Negotiating Normative Boundaries of Gender Mainstreaming and Post-Tsunami Reconstruction in Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, Indonesia." Review of International Studies 36(1):29-50.

Kamila, Raisa and Mifta Sugesty. 2008. "The Odyssey of Rani Monika [film]. MIRAS (Sekolah Jeumpa Puteh)."

Kantola, Johanna and Kevät Nousiainen. 2009. "Institutionalizing Intersectionality in Europe: Introducing the Theme." International Feminist Journal of Politics 11(4):459-477.

Kirby, Vicky. 2006. Judith Butler: Live Theory. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Koivunen, Anu. 2003. Performative Histories, Foundational Fictions: Gender and Sexuality in Niskavuori Films. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, Studia Fennica, Historica.

Lyotard, Jean-François. 1985. "Plastic Space and Political Space." boundary 2 14(1/2):211-223.

Mahmood, Saba. 2005. Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Massad, Joseph A. 2007. Desiring Arabs. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1991. "Introduction: Cartographies of Struggle. Thirld World Women and the Politics of Feminism." In Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, eds. Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Ann Russo and Lourdes Torres. Bloomington: Indiana University Press,1-47.

Mrázek, Rudolf. 1997. ""Let Us Become Radio Mechanics": Technology and National Identity in Late-Colonial Netherlands East Indies." Society for Comparative Study of Society and History 39(1):3-33.

Muhammad, Raihan Putry Ali. 2002. Remaja Putri Dalam Bingkai Kehidupan Mawaddah wa Rahmah [Adolescent Girl At the Edge of 'Love and compassioned Life']. Banda Aceh: Biro Pemberdayaan Perempuan Sekretariat Daerah Provinsi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam.

Mäkinen, Arja. 2008. "OIkeesti Aikuiset - Puheenvuoroja yksineläjänaisen normaaliudesta, hyväksyttävyydestä ja aikuisuudesta [Really Adults - Expressions of Normalcy, Tolerance and Adulthood of Single Women]." Department of Social Policy and Social Work. Tampere: University of Tampere.

Oxfam. 2008. "Gender Review 13th February 2008."

Oxfam International. 2007. "Oxfam International Tsunami Fund: Third Year Report, December 2007."

Oxfam International. 2008. "Oxfam international Tsunami Fund: End of Program Report, December 2008."

Palin, Tutta. 2004. Oireileva miljöömuotokuva. Yksityiskohdat sukupuoli- ja säätyhierarkian haastajina [The Symptomatics of the Milieu Portrait. Detail in the Service of the Challenging of Gender and Class Hierarchies]. Helsinki: Kustannus Oy Taide.

Parker, Lyn. 2008. "Theorising Adolescent Sexualities in Indonesia - Where 'Something different happens'." Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 18 (October 2008).

Pemberton, John. 1994. On the Subject of "Java". London: Cornell University Press.

Phoenix, Ann and Pamela Pattynama. 2006. "Editorial: Intersectionality." European Journal of Women's Studies 13(3):187-192.

Pollard, Nettie. 1993. "The Small Matter of Children." In Bad Girls and Dirty Pictures: The Challenge to Reclaim Feminism, eds. Alison Assiter and Carol Avedon. London: Pluto,105-.

Presiden Republik Indonesia. 2005. "Annex 5: Presidential Regulation Number 30/2005 Concerning Master Plan for Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Regions and Communities of Province of Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam and Nias Islands, Province of North Sumatra. Detailed book Economy and Manpower."

Puar, Jasbir K. 2005. "Queer Times, Queer Assemblage." Social Text 23(3-4):121-139.

Richardson, Diane. 1996. "Heterosexuality and social theory." In Theorising Heterosexuality, ed. Diane Richardson. Buckingham: Open University Press,1-20.

Rossi, Leena-Maija. 2003. Heterotehdas: Televisiomainonta sukupuolituotantona [Hetero factory: TV Advertisements as Production of Gender]. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Rossi, Leena-Maija. 2006. "Heteronormatiivisuus: Käsitteen elämää ja kummastelua [Heteronormativity: Conceptual 'Life' and Queering]." Kulttuurintutkimus 23(3):19-28.

Rossi, Leena-Maija. 2007. "Queer + Identity + Intersectionality = Something Truly Disturbing?" In Disturbing Differences: Feminist Readings of Identity, Location and Power. University of Turku, 19 April 2007.

Saad, Hsaballah. 2008. "Peran Perempuan dalam Perspektif Sejarah dan Adat Aceh [Role of Women from the Perspective of Acehnese History and Adat] " In Seminar Raya Memperingati 100 tahun Wafatnya Cut Nyak Dhien, Badan Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak Provinsi NAD, 6 November 2008, Banda Aceh.

Shapiro, Michael J. 2009. Cinematic Geopolitics. London: Routledge.

Sharpe, Joanne and Imogen Wall. 2007. "Media Mapping: Understanding Communication Environments in Aceh. World Bank. Indonesian Social Development Paper No. 9."

Shiraishi, Saya S. 1983. "Eyeglasses: Some Remarks on Acehnese School Books." Indonesia 36(Oct 1983):67-83.

Shiraishi, Saya S. 2000 [1997]. Young Heroes: The Indonesian Family in Politics. Ithaca: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications.

Singhal, Arvind and Everett M. Rogers. 1988. "Television Soap Operas for Development in India." Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies 41(2):109-126.

Singhal, Arvind and Everett M. Rogers. 1999. Entertainment-education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Skuse, Andrew. 2005. "Voices of Freedom: Afghan Politics in Radio Soap Opera." Ethnography 6(2):159-181.

Storey, Douglas. 2000. "A Discoursive Perspective on Development Theory and Practice: Reconceptualizing the Role of Donor Agencies." In Redeveloping Communication for Social Change: Theory, Practice, and Power, ed. Karin Gwinn Wilkins: Rowman & Littlefield.

Tanesia, Ade. 2008. "Women, Community Radio, and Post Disaster Recovery Process." «www.isiswomen.org». Accessed September 2009.

Tuli, Priya. 2002. "The Color of Joy." «www.indoindians.com». Accessed July 2009.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2008. "UIS Statistics in Brief: Education in Indonesia." «http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/document.aspx?ReportId=121&IF_Language=eng&BR_Country=3600». Accessed February 2010.

United Nations. 2001. "Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action with the Beijing +5 Political Declaration and Outcome Document." ed. Department of Public Information United Nations: United Nations, New York.

United Nations. 2008. "United Nations Millenium Development Goals." «www.un.org/millenniumgoals/». Accessed October 2009.