The Archival Uncanny: A Family Lacuna

By Joseph Heathcott

[1] Ten solid Tennessee men sit for a photograph at the dawn of the twentieth century. Nine of the men are brothers, one the father. All of them are sharecroppers and farm laborers, their dusty ill-fitting clothes revealing something of their poverty. For several of them it will be the only time their image is captured. They give the camera a low, steady, back-country stare as the photographer seizes the moment.

[2] For their troubles, 120 years later we have a tangible relic that we can hold, regard, inspect, covet and treasure. But the two circles of blue ink hint at another presence, intangible and immaterial: two brothers are absent. Tragically for the men assembled, these two brothers were already dead by the time the photograph was made. They are a presence of an absence, missing and lamented. But it's more than that. Something is wrong in Western Tennessee, something that lurks below the photograph, below the moment of its creation. The brothers are not simply absent by death; they are absent, period. They left behind no records of their life on earth, except a trace of blue ink and a dim family story. For History, they do not exist.

[3] The archives that record the traces of lives are powerful engines of remembering and forgetting. And what is forgotten is as important as what is remembered. Sometimes what is forgotten can return, like a bad meal – a hard to digest diet of dead facts. Other times what is forgotten imbricates in ghostly traces, a kind of pattern language of social amnesia that weighs upon us across generations. Still other times, what is forgotten never could have been. It is not just the silence of the archive. It is the archival uncanny, the black hole of Historical absence, the vertiginous yawn of cold, indifferent nothingness.

[4] The two men who should occupy the spaces in the blue circles missed their chance to be part of our collective memory. Family lore tells us that they were born, they lived, and they died – from sinew and bone to earth and dust. But they passed through the mortal coil in just the right slipstream of time and space for their existence to be obliterated, hidden from the gridded logics of the archive and the instruments of historical reckoning.

[5] The photograph depicts James Etheridge Heathcott and his then-living sons in Weakley County, Tennessee at the end of the nineteenth century. James was born in North Carolina in 1839 and came to northwestern Tennessee with his parents while still young, probably because the region was more open to Catholic settlers. In 1856, James married Catherine Jolly, and they eventually had 19 children – 11 of whom reached adulthood. James and his brothers, like most men in the northwestern counties of Tennessee, fought on the Union side in the Civil War. They never owned property, eking out a living as sharecroppers in the flood-prone plains, hills, and oak-hickory forests of Western Tennessee. James could not read or write: he made his only known signature, on his marriage license, with an "X". He died in Weakley County in 1918.

[6] For the rare occasion of sitting for a group portrait, family lore holds that the men organized themselves in birth order. The old patriarch is seated at the far right, and his sons are arranged right to left in order of birth, with the oldest four in the front row, the younger five in the back row. Thus, the oldest son, Emerson, is seated second from right, and the youngest son, George, is standing at far left. At some point, somebody penciled in numerals reflecting the order in which the men were born, seen faintly in the undermatting below the bottom row and above the top row. The numerals are of a style common to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And while we do not know who annotated the photograph, their gestural intent lives on, a graphic clue to the otherwise hidden correspondence between birth and seating orders.

[7] For sharecroppers in rural Tennessee at the turn of the last century, there were few opportunities to leave traces of one's existence behind. A photograph is one such opportunity, though often identification breaks down as names become detached from the images, or the images themselves fade to grey. How many times have we perused the bins at antique shops full of old sepia photographs and tintypes depicting legions of the no-longer-known? The heart aches for the faces separated from a memorial gaze, for the images decanted of consanguineous identity. And yet, the very fact of their materiality holds the promise, however latent and remote, that these photographs could be repatriated to their families, that somehow their bulk derangement could give way to blood reunion. Or perhaps these likenesses can be recruited into new identifications, their very materiality enabling the conditions through which new narratives of belonging might be composed.

[8] But these are possibilities unavailable to our two missing brothers, who never made contact with a photographic moment in the first place. Not only do they lack the presence in the family album that would secure them to coordinates of time, space, and memory; they left behind no images, period. They never connected to the visual mechanics of history, to the ocular speculum wherein modern identities coalesce. It is not even the case that their images are lost. They never even existed. After all, loss is melancholic. It plies our sentiment with a comforting predicate where people come into being and exit being within a hermetic past. But historical absence disquiets. It haunts us from the uncanny, from the unnerving grammar of the never-having-been.

[9] Beyond the photograph, there are also the moments when individual lives track through history, when we make contact with the instruments of governance and memory, and we leave our trace in the archive. In these moments a name can be recorded, a signature appended to a form, a notation made on a census schedule or plat map. One's corporeal passage can be measured through documents of vitality—birth and death certificates, baptismal rosters, wills and probate, muster rolls, land records and deeds. Many of these records repose in institutions dedicated to their conservation, and a growing fraction of them have crossed into the digital realm, keyword searchable and globally available. Other records molder in storerooms of county courthouses and church rectories, or languish in attics and basements and secret places. Meanwhile, there are records that take more intimate material forms, such as tombstones and family bibles, diaries and letters, family recipes and literary marginalia. Howsoever deposed, such documents premise historical existence and, indeed, contribute to the creation of the very historical subjects they record and contain.

[10] But as with the photograph, the two missing brothers never made lasting contact with the constitutive documents of history. They were born after the 1880 census, and died before the 1900 census. The 1890 census, the only one that could have captured them, was destroyed in a fire in Washington, DC. They came and left the world before the State of Tennessee began recording such passages. They never married, and so never affixed their names to a registry document. They died before they were old enough for military service, and no record of their baptisms – assuming they were baptized – have been found. They are most likely buried in unmarked graves, as no tombstones exist in Weakley County to record their brief lives. They never owned property, so their deaths did not result in probate.

[11] What little we do know about these brothers comes only through oral tradition. They were twins, born in 1882 or 1883. They died within months of each other, both aged 17 and both from gangrene. The first succumbed from a broken leg following a fall from a mule. The second died after undergoing botched dental surgery to remove a second set of adult teeth. It is an all too familiar story in rural America in the nineteenth century: the injury, the makeshift triage, the infection, the morbid tissue, the septic shock. How these brothers must have suffered. How the family must have stood by helplessly while the brothers grew fevered, rigid, and sick. But the wonderfully specific means of their agonizing deaths obscures the reality that we know nothing else about them, nor is it likely that we ever will. They persist as ghosts, dark ethereal densities rattling the stories the family tells about itself.

[12] What does it mean to be so thoroughly absent from the archive in this way? If you do not leave behind traces of your life, do you exist? If your life is never recorded in the instruments of official memory, and therefore unrecoverable through exegesis, are you lost to history? The archive sucks up the facts of our lives, but it does so unevenly; it is an always incomplete and unstable site. Sometimes what is lost to the archive remains crystallized in portraiture, or is evident in the handscrawl record of births and deaths in the family bible, or resonates in stories told between generations. We are formed ontologically at the intersection of manifold assemblages – as bodies of blood and bone, as creatures of particular times and places, as constellations of light on the photographic surface, as subjects in the flow of stories, as objects of the historical mien. When we pull on any of these threads, parts of us dissolve, fade, disappear. We are always embroiled in struggles against un-becoming and, worse, never-having-been.

[13] Archives are diagrams for remembering, but also for forgetting, and all the more so in the context of modernity. Forgetting is as basic as recollection to the archive in the formation of modern ways of knowing, in the emergent taxonomies and classifications of modern governmentality. The missing brothers are by no means some ante-modern subaltern class, existing apart from the machinery of the knowing state. Indeed, their forgotten status arises precisely from the techniques of official memory-making. After all, their parents and siblings all left behind traces of their existence, both in texts and images. Even in rural Western Tennessee, remote and poor at the end of the nineteenth century, instruments of governmentality existed to capture them. But these instruments work on a gridded logic, producing the archive through multiplication of official points of contact arraigned across geography and habitus. From time to time people (facts) can be lost IN the archive, but the absent brothers never made direct contact WITH the archive, never triggered the flow of information through memorial instruments. As a result, they nearly succumbed to the deracinating ontologic of history, the erasure of being through the never-having-been.

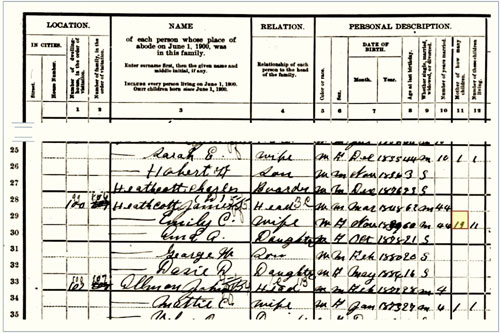

[14] But the brothers have not succumbed quite yet for three paradoxical reasons. First, the formal instruments that failed to capture them directly nevertheless caught their indirect trace in one instance: the 1900 U.S. Census. On June 9th of that year, enumerator Joseph Fowler asks Emily Heathcott to account for herself as the "mother of how many children" (recorded as 19) and then to reckon the "number of these children living" (recorded as 11).

[15] Tucked away within the differential sum of these two numbers are the agonies of loss that saturate the hardscrabble landscape of Western Tennessee. Surely the act of counting dead children for the enumerator must have loosed the stores of grief, as fallen loved ones are recalled to memory in that moment. In any case, the two brothers lurk there in starkly drawn numerals, fixed to the grid of history in row 29, column 11, Sheet 6, Enumeration District 136, Supervisor District 9, Civil District 24, Weakley County, Tennessee.

[16] Second, the very act of publishing this essay about their non-existence brings the two brothers, however tentatively, into the narrative flows of history. The essay draws upon three domains of evidence – orality, text, and image – localized in family stories, official documents, and an old photograph. Threading these disparate strands, each with their own discursive and material peculiarities, a story emerges about two brothers who died young in rural Tennessee some 120 years ago. Now in published format, the essay conveys its discovered characters to the archive, embedding them in the vast library that comprises the historical record. The brothers begin to vibrate from the dark places of history, to worry the archive with their absent presence, to co-author the story of their own non-story.

[17] Third, the blue circles on the photograph indicate the existence of absence, a latency around which we might form new accounts of past lives. Resolving out of nothingness, the brothers come to inhabit the image in the trace of blue ink. We do not see their faces: the circles conscribe only a surface of grime against the faded wallpaper backdrop. Nor do their nine living brothers open up room for them as they stand for posterity, awaiting the camera's gaze; they have made their peace with loss and closed ranks around the living. But surely the two brothers lurk there, immanent, implied. The blue circles shimmer on the image surface as they reach into the photographic moment, charged with the potential to render lost souls as found subjects of history.

[18] How wonderful it would be for the purposes of this essay if we could meditate on the unknown hand that inked the blue circles, quietly recording some deep yearn for loved ones long gone. It would add enormously to the romantic appeal of the story. But it is not like that. I drew the circles; or, to put it more accurately, I added them as a layer to a digital file using Adobe Photoshop. It is a provocation, an alteration of the time-space of the image, from its constellation in a rare photographic event, to its unfathomable accruance of antiquity, to its manipulation on a Mac desktop. Does it matter? Am I guilty of historical misprision? The answer depends on how we define history.

[19] Placing the image-bearing object (the photograph) onto the scanner bed, I tore the image violently out of its ancient material form. The cold optics of the scanner dislocated the image line by line from the apparent "thingness" of the photograph, its topographies of light and dark activated against the epitaxial layer of a capacitor array. The capacitors transmitted their information to a charge-coupled device, storing the information as a voltage sequence. From there, software routines sampled the information algorithmically, converting it to RGB values on a grid comprised of millions of pixels. These pixels were then rendered as a digital file through lossless compression standards supplied by Aldus's Tagged Information File Format (TIFF). A further round of manipulations in Adobe Photoshop – higher contrast, increased exposure, and shifts in the red and white levels – brought the figures out from their faded gloom. Finally, I sent the image from my desktop as an email attachment – saved in a lossy compression file interchange format (FIF) created by the Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG/JFIF) – to the desktop of the editor, who in turn manipulates the file for publication on the web.

[20] In converting the photographic image into a digital file, I have given it a new materiality. Left behind is the cardboard backing, the flaking edges, the eye-watering dust, the blistered surface, the charcoal pencil marks, the 'scratch and dent' dimensionality with all the sticky accretions of time. Now I see the image on a large liquid crystal display monitor, oversized, color-saturated and luminescent. While I treasure these tactile accretions and the sculpting effects of time, the digital image obliterates the object's topological condition through the ruthless application of coded routines. Indeed, the image – borne by (and now dislocated from) its vessel of containment – has traveled far from its creation on a Western Tennessee farm to its digital recreation in New York City a hundred and twenty years later.

[21] So we have two images of the solid sons of Tennessee, one presented through the haptic form of the photograph, the other through the ethereal form of digital rendering. What's the difference? Both are mechanical reproductions, technics of information capture, storage, and circulation. Both images collapse the temporal into the spatial, simultaneously embodying and obscuring the logics of their production. But the photograph that I hold in my hand is an object that was regarded, touched, or even owned by one or more of the men depicted. It is an artifact of a moment, a parcel posted from past geographies, a temporal prosthetic that extends faulty human memory and a device that records the wear of the hands that hold it. The digital image is an artifact of this time, a file that exists as a packet of instructions at the mercy of my CPU, welded to the gloriously inhuman grid of binary code.

[22] But it is the digital file that opens new possibilities for the image, rescuing it from its prison of hand-held nostalgia. With the digital version I can separate the image from its material embodiment, shedding the phenomenal obscurance of the photograph to gain the image itself. In this way, I can experiment with a range of affective interventions, settling on one that best suits the task. That task is not to convey some "meaning" inherent to the image, but rather to ruminate on the problem of non-existence through the lacunae of the lost brothers. The digital version allows me to play with the representation of the unrepresentable, and to second a new narrative to an image that otherwise cannot contain it.

[23] In making this intervention, I hope to enjoin the photograph more completely to the family narrative, but in a way that simultaneously demarcates an absence and indicates a presence. I imagine the missing boys to be tall and gaunt, with ruddy complexion and sandy cowlicked hair. I speculate about where they might have stood for the photograph, rubbing against the broad shoulders of their older brothers. I see their rough clothes as links in a chain of significance that connects the photo-generative moment to the conditions of rural Southern poverty, the sufferance of tenancy, the tragedy of early death, the extinguishing of memory, and the nature of being in the modern archival state. I think about their steely eyes looking out over the land that would eventually swallow them up.

[24] In the end, the two brothers are not really lost, for "loss" implies the possibility of presence. They are disimmanent, vacated from modernity. The empty circles that attempt their recovery can only emphasize the stark reality of their non-existence, the phantasm of the never-having-been. Over and against the efforts of a family to remember, the missing brothers show us how to be forgotten. While we cling to a story, we lose them. We don't even know their names.

Contact:

Joseph Heathcott

The New School

66 W. 12th St., Suite 401

New York, NY 10011

Phone: 1 347 751 5323

Email: jheathcott@gmail.com