Unburdening Life, or the Deleuzian Potential of Photography

Michael Kramp

Lehigh University

dmk209@lehigh.edu

[1] Etienne-Louis Boulée's Interior of a Library (c. 1798) details his plan for transforming "a ... courtyard ... into an immense [amphitheatre-like] basilica lighted from above ... [with] attendants spread about so they could pass the books" from tier to tier. Boulée's vision for a library of extensively-archived material serves as an emblem of the Enlightenment model of knowledge that is at once authorized and accessible. The room is immense and efficient; it is a remarkably well-organized space in which all volumes are neatly categorized, properly retrieved, and meticulously re-shelved. In addition, information is neither restricted nor occluded; rather, it is exposed, made visible, and the immense depth of field in Boulée's drawing invites us to speculate how the library may very well continue, or receive an addition in the future as more knowledge becomes legitimated and collected. Boulée envisions how the open exchange of ideas might replace the dark coves of private pre-modern libraries, and he imagines a space in which the common pursuer of wisdom might take the place of the elite gentleman-scholar. But Boulée's vision is, of course, futuristic, and his wikepedia-esque ideal is unattainable without the technological, political, scientific, and epistemological developments of the nineteenth century, including the announcement of photographic technologies in 1839, which quickly became indispensable to the hope of making Boulée's dream a material reality. Photography provided the capacity to record detailed information accurately and reproduce countless copies to ensure that knowledge was both widely disseminated and never lost or perverted. In addition, the proliferation of photographic technologies throughout the nineteenth century enabled ordinary individuals to create their own visual records and contribute to established collections. Most importantly, perhaps, photography offered a presumed objectivity. In short, it could ensure that Boulée's Enlightenment project of fixed, common, and authoritative knowledge became a pragmatic component of everyday life.

Boullé?e, Etienne Louis, 1728-1799. Interior of a Library.

Thaw Collection, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

[2] Numerous scholars have completed impressive critical studies detailing the cultural impact of the rise of photography on modern systems of knowledge such as archives, museums, and libraries, but for reasons that are quite sound, we have not yet seen an abundance of Deleuzian treatments of photography, its history, or its aesthetic potential.[1] Deleuze's relatively sparse comments on photography suggest neither his philosophical interest in the art form nor his confidence in its potential to create new concepts or relationships. Instead, like many scholars, he often discusses photography as an important instrument of the Enlightenment system of knowledge. Alan Sekula provides an example of this now-standard critical reading of the art in his canonical essay, "The Body and the Archive;" he cogently explains how "photography doubly fulfilled the Enlightenment dream of a universal language: the universal mimetic language of the camera yielded up a higher, more cerebral truth, a truth that could be uttered in the universal abstract language of mathematics . ... Photography promised more than a wealth of detail; it promised to reduce nature to its geometric essence" (17). Deleuze is not only a critic of this promise of fixity; he fundamentally disputes its reality, encourages us to resist its organizing effects, and identifies various creative strategies for the disruption of its mechanization. Creative art is undoubtedly a vital Deleuzian tactic for such endeavors, and he writes extensively on the potency of music, literature, the cinema, and modern painting. He specifically points to art's perpetually generative capacity. Indeed, he famously concludes, "What the artist is, is creator of truth, because truth is not to be achieved, formed, or reproduced; it has to be created. There is no other truth than the creation of the New: creativity, emergence" (Cinema 2 146).[2] A Deleuzian aesthetics, then, must foreground not simply the making of new truths, realities, or ideas, but their continual and immanent re-creation. In effect, Deleuze's notion of art directly contradicts Boulée's vision for secure and certified knowledge. For Deleuze, art repeatedly questions "official" data; he presents creative works as challenges to dated empirical encounters that have been transformed and organized into archived authorities.[3] Cultural scholars—including Deleuze—have somewhat routinely assessed photography as an aid of this Enlightenment ambition to collect and arrange knowledge of human experience, but this special issue of Rhizomes invites us to consider the Deleuzian potential of the art, its specific formal features, and its quotidian technology and practice to create anew—to establish new truths, new kinds of relationships, and new sensations. In short, this issue will read Deleuze against Deleuze to reconsider photography's artistic capacity to engage with and generate new experiences of reality.

Deleuze's Critique, the Challenge to Unburden Life, and the Diagram

[3] We clearly face a stiff challenge in our attempt to proffer Deleuzian treatments of photography as our critical project brushes up against the fact that Deleuze does not invest photography with the creative and re-creative potential that he associates with both cinema and modern painting. In short, while he highly values other visual artistic forms, he seemingly presents photographic texts as stagnate documents or tools that produce certainty, organize bodies and desires, and iterate hackneyed ideas. He even uses photography as something of a foil to demonstrate the innovation of the cinema and the originality of modern painters. In Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation (1981), he notes how "photography has taken over the illustrative and documentary role, so that modern painting no longer needs to fulfill this function, which still burdened earlier painters" (10). He later explains that "photographs are ways of seeing, and as such, they are illustrative and narrative reproductions or representations ... . they are what is seen, until finally one sees nothing else." He treats the photo as an instrument for reproducing representations of reality—a device that iterates images until they are ossified as established stories, icons, or even stagnant perceptions. Indeed, like Bergson before him, Deleuze compares photography to what he identifies as a reductionist model of perception: "what we see, what we perceive, are photographs" (74).[4] The photo is, in effect, an always-already passé sensational experience that numbs our sensitivity to the ongoing vitality of life and provides us with an efficient understanding of the dynamism of our world. But it is compelling that Deleuze theorizes both the quotidian nature and the liberatory potential of photography; he treats it as a common, everyday visual experience that, despite its aesthetic and technological limitations, emancipates the modern painter to explore new artistic opportunities. This special issue of Rhizomes repeatedly provides artistic examples and critical strategies that invite us to see photography as replete with the power to unburden and emancipate that Deleuze associates with both film and painting. Indeed, one way to think of this project of reading Deleuze against Deleuze might be to ask: if photography can free painting and painters to pursue novel creative opportunities, can it likewise free itself, photographic practitioners, and even viewers to create and re-create anew?

[4] To answer this question and develop the aesthetic possibilities it incites, we must turn to—not avoid—Deleuze's assessment of the formal features and limitations of the photograph. In Cinema 1 (1983), he makes a useful distinction between photography and film that may surprisingly allude to the creative potency of the former. He writes:

The difference between the cinematographic image and the photographic image follows from this. Photography is a kind of 'moulding': the mould organizes the internal forces of the thing in such a way that they reach a state of equilibrium at a certain instant (immobile section). However, modulation does not stop when equilibrium is reached, and constantly modifies the mould, constitutes a variable, continuous, temporal mould. (24)

For Deleuze, photography crafts and contains forces until balanced and still, while film continuously adjusts to the energies of forces to portray temporal continuity, the discordance of time and place, and the integration of the virtual and actual image. Unlike the cinema, the photographic image, according to Deleuze, seeks to enclose, surround, or even control the dynamism of life. It seems incapable of defamiliarizing reality like Bacon's painting, and too dependent on framing or freezing images to represent time or movement in time. While Deleuze often speaks of photographs as if they were volumes within Boulée's library—i.e. static images that reproduce ostensibly fixed information—his comments may ultimately unveil the creative potential of the camera's still image. Photography may try to mold our sensational experiences, but it does not necessarily succeed; as Deleuze suggests, "modulation does not stop," and the photo's formal attempt to enclose forces makes it specifically sensitive to the ongoing rush of modifications and sensations. The photo's formal limitations, according to Deleuze, reveal themselves, but rather than viewing this as a detriment to the art, I want to uphold it as an indicator of its power—i.e. it ultimately cannot contain or restrict vital and dynamic forces. In addition, even as it tries to document our material encounters as fixed shots of reality, the photo leaves itself vulnerable to creative manipulations, revisions, editorial captions, and, perhaps most importantly, aesthetic engagements. And in what I believe is a truly Deleuzian aesthetic approach, I want to invite us not to think of the ontology of photography or individuals shots, but rather to explore the energies and possibilities of images.

[5] While we often associate Deleuze's aesthetics with his works on Bacon, Leibniz, and the Cinema books, all published in the 1980s, his oeuvre is marked by this concern with the need to create, recreate, and avoid the stultifying effects of catalogues or archives. In two essays that bookend his career, "Nietzsche" (1965) and "Immanence: A Life" (1995), we observe both his enduring critical commitment to aesthetics as well as a useful strategy for theorizing—and hopefully re-theorizing—his formal treatments of film and photography. In these short pieces written thirty years apart, he clings to the power of creativity within the debilitating context of what he terms "the degeneration of philosophy" ("Nietzsche" 68). He notes that philosophy once operated as a legislator, as a maker of ideas, but grows "submissive" as Western thought wrestles with the weight of ontological certainty. He explains how the philosopher was once "the critic of established values ... [and] the creator of new values and new evaluations," but s/he has now become "the preserver of accepted values." He speaks of the Enlightenment philosopher as if s/he were a blasé photograph, merely reproducing and maintaining already known and already indexed truths; and Deleuze concludes that the lover of knowledge, much like such a photo, "claims to be beholden to the requirements of truth and reason; but beneath these requirements of reason are forces that aren't so reasonable at all: the state, religion, all the current values" ("Nietzsche" 68-69). The work of philosophy becomes akin to a census in which practitioners track, record, and ultimately collect all the reasons man gives himself to obey. Philosophy, according to Deleuze, was once the creator of our very understanding of reality, but Western paradigms—and specifically the Enlightenment model of metaphysics that he traces from Socrates through Kant—have relinquished their creative legacy in favor of service to "the state, religion, all the current values." This shift has built the kinds of libraries and archives that Boulée imagined, fueled the rise of the organizing social machines, and regulated rhizomatic creativity.

[6] Deleuze, however, upholds the enduring power of creative art to produce new aesthetic, intellectual, and conceptual possibilities—possibilities that emancipate knowledge from efficient archives, modern disciplines, or other codified systems of thought. While Boulée's sketch reminds us how mechanically-reproduced images might contribute to and reinforce such organized collections of information, and Deleuze often seems to associate the art form with this practice of failed philosophy, I again propose to read Deleuze against Deleuze to explore the creative potential of the photographic arts and their technologies. In his essay on Nietzsche, Deleuze concludes, "to create is to lighten, to unburden life, to invent new possibilities of life. The creator is legislator—dancer" (69). As we alleviate the weight, pressure, and even the sense of responsibility from life and art, we expose it to a multiplicity of sensations and ideas. This process is perhaps most challenging when representing or describing an individual life—a philosophical difficulty and artistic experiment that Deleuze addresses in "Immanence: A Life." Photography, of course, has long been involved in depicting the individual life through portraiture, albums, and annual collections, and we often understand this artistic work as preserving a specific and particular conception of "a life," but in this late essay, Deleuze urges us to appreciate the vast complexity of our bodies and existences. He asserts, "A life is everywhere, in all the moments that a given living subject goes through and that are measured by given lived objects: an immanent life carrying with it the events or singularities that are merely actualized in subjects and objects" (29). He stresses the omnipresence of a life, reminding us of its immanence, its ongoing vitality, and its resistance to framing and organizing structures.

[7] As art struggles to "lighten" and "unburden life," it exposes the diversity and various relationships of a life—an aesthetic capacity that Deleuze associates with post-War cinema. Film, for Deleuze, can produce immanence that the photo ostensibly restricts, but a Deleuzian approach to photography allows us to theorize the perpetuity of our sensory experiences; the photo may momentarily suspend such ongoing vitality, but it likewise points to new sensational possibilities that we have not yet even fathomed, or creates a nexus to past sensations long dismissed. This issue offers numerous critical and artistic renderings of such immanence that encourage and at times compel us to imagine photography as on opportunity to create new assemblages and new lines of flight. Late in "Immanence: A Life," Deleuze addresses the inevitability of sensations yet to be experienced; he explains: "A life contains only virtuals. It is made up of virtualities, events, singularities. What we call virtual is not something that lacks reality but something that is engaged in a process of actualization following the plane that gives it its particular reality" (31). While Boulée's idealized system hopes to individualize data gleaned from sensory engagements of life, neatly separate it, and efficiently retrieve it, Deleuze highlights the messiness and the modulations of both life and art. Photography—and canonical readings of photography—have certainly contributed to fulfilling Boulée's vision, but this special issue of Rhizomes invites us to theorize photography's creative power to legislate and dance, to produce knowledges and experience that remain diverse and allusive, and to imagine new kinds of relationships and sensations that at once have efficacy and explosive untapped energies.

[8] Such a Deleuzian theory of photography is perhaps best understood as emergent, and I want to suggest a Deleuzian context for studying photography that highlights this sense of emergence, i.e. the diagram. In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari explain that "the diagrammatic or abstract machine does not function to represent, even something real, but rather constructs a real that is yet to come, a new type of reality" (142). This model of creative production shifts our aesthetic expectations, discouraging us from asking what is represented and encouraging us to consider how we might re-represent the actual. Tom Conley defines Deleuze's notion of the diagram as "the sum of creative actions that include marking and drawing lines by way of chance; then cleaning, sweeping, or wiping areas with spots or color; finally, applying paint from varied angles and at as many different speeds" (Logic 144). Conley adds, "the term designates a mapping of the elements of chance, a selection and distribution of clichés, a condition that shapes creative accident" (Logic 145). I want to think about the ability of the photograph to function not as a tool of the Enlightenment project but as a diagram—a "creative accident" that might unburden the immanence of life. Indeed, I want to shamelessly consider the possibility that others might see the Deleuzian potential in the photograph that Deleuze himself did not. I am excited to present articles that consider how photography might accomplish Deleuzian creative work, what kinds of photographic technologies or innovations might promote new concepts or relationships, and how photographs might deterritorialize the organized system of knowledge that Boulée's drawing forecasts.

Representation, the Cliché, and the Figure

[9] Boulée's vision of modernity depends upon an aesthetic investment in stable and secure accounts of experiences that we have traditionally found in photography, but Deleuze develops an alternative aesthetic theory and practice that alters both Western understandings of representation and the creative possibilities of/for the photographic image. Deleuze relocates the very focus of discussions on art when he announces: "In art, and in painting as in music, it is not a matter of reproducing or inventing forms, but of capturing forces" (Francis Bacon 48). He displaces the question of mimesis and accentuates the issues of vitality and latent energy. As Daniel W. Smith notes in his introduction to the English edition of Francis Bacon, "the question Deleuze poses to an artwork is not 'What does it mean?' but rather 'How does it function?'" (xii). Rather than obsessing with what is documented or debating how accurate such reproduction might be, Deleuze is concerned with the operation or, more accurately, the operationality of art—how it works, or even how it might work, to produce sensations, desires, and relationships that disrupt the organizing procedures of modern systems of knowledge. This shift allows Deleuze to reframe the priorities of aesthetics; he foregrounds the sensations of art, and the conditions that produce such effects, rather than the representations of art or its contribution to cultural institutions of order. His notion of the cliché is crucial to both what he identifies as the proclivity of art to reify established systems of knowledge and its creative possibilities. In Cinema 1, Deleuze defines clichés as "floating images, these anonymous clichés, which circulate in the external world, but which also penetrate each one of us and constitute his internal world, so that everyone possesses only psychic clichés by which he thinks and feels, is thought and is felt, being himself a cliché among the others in the world which surrounds him ... . clichés and psychic clichés mutually feed on each other" (208-9). Clichés function as producing-machines—both in our material reality and in our psyches; as always-already thought ideas, they secure and stabilize intellectual, artistic, or corporeal energies, and also serve to inhibit new creative relationships or forces.

[10] In Francis Bacon, Deleuze specifically refers to photographs as clichés that "are already lodged on the canvas before the painter even begins to work" (12). He presents photography as a source of hackneyed representation that art must work to disrupt. But it is important to note that, for Deleuze, the successful artist can neither merely avoid, indict, or transform such clichés, for as he notes, these strategies "[leave] the painter within the milieu of the cliché, or else [give] him or her no other consolation than parody" (Francis Bacon 72). Instead, to create art that deterritorializes the normalizing work of clichés, artists, according to Deleuze, must confront them and work through such familiar representations, specifically those (re)produced by the photographic camera. Not surprisingly, he upholds Bacon as an artist who engages such clichés and creatively embraces chance to produce disruptive sensations and even violent effects—and it is not a coincidence that Bacon was likewise drawn to photographs. Deleuze even points out how Bacon's artistic accomplishment "arises in relation to photography." He notes that Bacon "is truly fascinated by photographs (he surrounds himself with photographs; he paints his portraits from photographs of the model, while also making use of completely different photographs)" (Francis Bacon 74). Although Bacon himself "ascribes no aesthetic value to the photograph," he worked with them to create his revolutionary paintings; he relied upon the camera's image to help him deterritorialize fixed understandings of material reality. Neither Deleuze nor Bacon seems to value the artistic potential of the photograph, but each recognizes the role of the mechanically-produced image in the creative process; and Deleuze's treatment of Bacon's interest in photography invites us to explore if it can likewise engage clichés—even clichés generated by other photographs—to accomplish a similarly disruptive aesthetic project.

[11] Deleuze's hope for such potent art begins with an acknowledgment that "clichés and probabilities are on the canvas; they fill it, they must fill it, before the painter's work begins," and he offers a radical plan for displacing these clichés: "the reckless abandon comes down to this: the painter himself must enter into the canvas before beginning. The canvas is already so full that the painter must enter into the canvas. In this way, he enters into the cliché, and into the probability." As artists struggle to produce dynamic sensations, they must embrace the canvas and its territorializing clichés. To escape these organizing formulas, Deleuze encourages us to relish the creative opportunities outside of the realm of probability, namely the possible; he writes, "it is the chance manual marks that will give him a chance, though not a certitude" (Francis Bacon 78). The camera is surprisingly well suited to produce such energies, show random moments of time and space, and frame arbitrary energies. We may not privilege or even recognize this Deleuzian potential of the photographic device, but its technology is designed to generate such singular moments of aesthetic engagement; its images are fundamentally of a moment, and although such images can clearly develop into clichés, I want to maintain that they are also open to the unpredictable, impulsive, or even violent marks of creative art. Photos may clearly be deployed to establish objective certitude, but this Enlightenment goal is most assuredly not intrinsic to their material production or their artistic form; photographic images can become clichés, but they can likewise manipulate such clichés to become disruptive art that creates new possibilities for sensations within a singular moment.

[12] Since many of our visual clichés are attributed to photography, it is, as an art form, keenly attune to hackneyed illustrations. Challenging, destabilizing, or redeploying such illustrations requires an aesthetic self-consciousness that empowers us to identify the always-already seen—a critical and creative skill that Deleuze highlights in his treatment of modern painting. He explains how "the painter does not have to cover a blank surface but rather would have to empty it out, clear it, clean it." Artists must realize that they create "on images that are already there, in order to produce a canvas whose functioning will reverse the relations between model and copy" (Francis Bacon 71). To function as Deleuzian art, photography, likewise, must unabashedly recognize, accept, and incorporate the "already there" to explore new images and random sensations that could displace the normalizing operations of the regurgitated cliché. Deleuze discusses this process through his assessment of the figure and the organizing regulation of figuration. Smith offers a helpful working definition of these terms; he writes: "whereas 'figuration' refers to a form that is related to an object it is supposed to represent, the 'Figure' is the form that is connected to a sensation, and that conveys the violence of this sensation directly to the nervous system" (xiii). Figuration denotes our aesthetic expectation—the anticipated resolution and arrangement of clichés that contributes to our modern classification of ideas and realities. The Figure, however, is immediately and intimately tied to sensation; it causes an intense sensual experience that becomes disruptive, excessive, or even decadent. Deleuze quite bluntly instructs: "painting has to extract the Figure from the figurative," and he again identifies Bacon as a successful practitioner of this technique (Francis Bacon 10). Bacon, according to Deleuze, produces art in which "the Figure itself is isolated." This strategy effectively "avoid[s] the figurative, illustrative, and narrative character the Figure would necessarily have if it were not isolated" (Francis Bacon 6). Bacon, in effect, exploits the figurative cliché to expose the latent creative energy of the Figure.

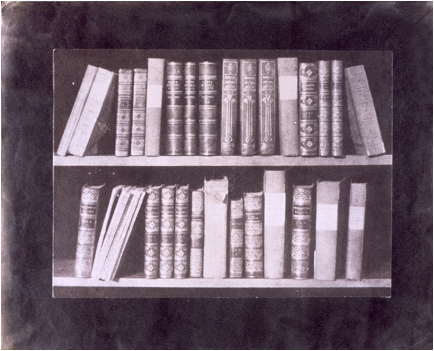

[13] By detaching the Figure (i.e. the form, the body, or even the experience that produces sensation), Bacon's images both use and resist the territorializing effects of preordained stories, rehashed representations, and stock characters. And again, Deleuze identifies the role of photography and other visual technologies in this creative process. He explains: "Figuration exists, it is a fact, and it is even a prerequisite of painting. We are besieged by photographs that are illustrations, by newspapers that are narrations, by cinema images by television images" (Francis Bacon 71). Deleuze urges us to understand the breadth and depth of visual figuration; we are flooded with reproduced and reproducible images that inhibit our creative ingenuities. Bacon employs such instruments of figuration to help him isolate the figure, its sensations, and its forces, and this issue illustrates how photography is likewise aesthetically and technologically capable of engaging figuration. It can use various artistic strategies, including creative framing, digital manipulation, and perhaps most importantly the willing acceptance of spontaneous forces and vital energies to violently dislocate the figure from its territorializing figuration. We often use the photograph to suspend specific points of time, memorialize an individual person, or record a particular place, and each of these techniques can repeat clichés, restrict "a life," and contribute to figuration; but each of these techniques can also capture and isolate creative energies if we remain open to the violence and dynamism of the sensations of a moment, a person, or an experience. This willingness to embrace the chaotic unpredictability of sensation, moreover, empowers us to avoid the structuring powers of pre-established narratives.

Narrative, Photographic Time, and the Crystal Image

[14] Such a model of aesthetic engagement allows us to experience the spontaneity and dynamism of artistic creations not as mementoes to be remembered, corrected, or archived, but as moments to relish and share—with the past and the future. Communicating such artistic experiences, however, engenders additional difficulties that threaten to contain or even deaden their creative efficacy, for as we relate the importance of art, beauty, or sensation to others through stories, we once more risk normalizing aesthetic experimentation. Deleuze specifically addresses the challenge of narration, which he treats as "the correlate of illustration." He explains how "a story always slips into, or tends to slip into, the space between two figures in order to animate the illustrated whole." A story, according to Deleuze, yokes similar (or even disparate) forces together, fashioning a relationship and a unity; it strives to contain the explosive energy of the Figure, iterate clichés, and craft neatly ordered resolutions. Such conventionality inhibits our ability to reveal powerful sensations to others that might build new kinds of relationships and threatens to relegate truly creative art to a solipsistic exercise. Deleuzian art, then, must strive to avoid the codifying effects of narrative, and he advocates, "isolation [as] ... the simplest means, necessary though not sufficient, to break with representation, to disrupt narration, to escape illustration, to liberate the Figure: to stick to the fact" (Francis Bacon 6). He points to Bacon's ability to detach the Figure from its hackneyed associations or traditional legacies as a successful example of isolating vital forces of life from the order of a story. Bacon violently removes the sensation of the Figure from its territorializing contexts, forcing us to see its raw energy, uncontaminated by aesthetic or narrative expectations.

[15] Photographic technologies are no doubt vulnerable to this territorializing activity of the narrative, but they may also have a distinct aesthetic capacity to destabilize predictable stories. We inevitably place photos in relationships: to measure age and the passing of time, to compare various locations, and even to determine minute differences between individuals. These relationships undoubtedly expose photography to narratives that aggressively offer to create hackneyed transitions and generate mundane conclusions. The camera, however, is also well equipped to isolate the Figure, confidently cling to the fact, and resist crass connections. As an individually-framed visual image, the photograph is an isolating medium, and when photographers successfully free the forces of sensation from the modern impulse of order and structure, they can disrupt the totalizing tendencies of the narrative. Damian Sutton, in his groundbreaking study Photography, Cinema, Memory: The Crystal Image of Time (2009), admits "ordinarily we place photographs into sequences and contexts—the family album, the newspaper, the filmstrip," but he theorizes, "whenever the photograph is left without a motor-material connection, either through dislocation or, alternatively, entanglement and involution, signification can be radical and random" (55). We may use photos to establish conventional accounts or normalizing relationships, but such narrative continuity and temporal linearity is an aesthetic strategy of viewers and not integral to the form of photography. Rather, the temporality of the photo is always jarring, because as an art form it isolates a moment in space and time; but the limitations—or rather the expectations—of our theories and conceptions of beauty often prevent us from appreciating this disruptive work and prompt us to rebuild typical relationality or linear development through story. Deleuze is, of course, extremely excited about the temporal possibilities of post-War cinema, but as Sutton notes, Deleuze's revolutionary theory of the time-image originates from "the photographic" (xi). Sutton explains how "cinema and photography are badly explained by the binary organization that sees them as representing mobility and immobility, life and death," and concludes, "to understand the photographic image is to understand the glimpse of immanence it so often affords us" (xii). It is in such glimpses of immanence that photography accomplishes Deleuzian aesthetic work; it cannot show movement or temporal disjunction like cinema, and it often lacks the tactility of painting, but it can isolate Figures and sensations to provide a momentary vision of new possible relationships that resist the totalizing effects of narrative.

[16] Sutton is very helpful in theorizing such photographic potential, even as he acknowledges the aesthetic legacy of the photograph. He astutely observes, "the reason why Deleuze never fully explores the photograph as time-image is simple and direct: its part in the sensory-motor schema renders it antithetical to Deleuze's conception of a direct image of time" (45). The photograph has traditionally been viewed and understood as a reproduction of our sensory experiences of material reality. This deeply entrenched belief may date from William Henry Fox Talbot's expressed ambition "to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!" ("A Brief Historical Sketch" 29). Numerous recent critics, including Daniel Novak and Jennifer Tucker, have called into question this legacy of photography's objective fidelity to sensory experiences of nature,[5] but we are still haunted by the supposed authority of the photograph, its fixity, and its utility to modern systems of knowledge. Sutton, however, encourages us to imagine its potential to produce alternative narrative and temporal effects. He points out how "the instantaneous photograph reverses our relationship to duration ... . With a photograph we are presented with an image that is static but that nonetheless can give a powerful sensation of time passing" (38). The photo is ostensibly a fixed image of isolated time, but it likewise produces a sensation not only of time past, but of the perpetuity of temporality—of time passing; time continues, and is most assuredly not ordered into safe or structured patterns as it moves beyond the borders of the frame. Sutton refers to such "time passing" as the "forgotten time of the photograph" (39). Deleuze often seems to demote photography to a minor blip in the emergence of the cinema and technological aid to the innovations of modern painting, but Sutton encourages us to recognize the temporal possibilities of the photo as a latent creative potential central to a Deleuzian theory of the visual image.

[17] Sutton even adapts Deleuze's notion of the crystal-image to help us imagine the capacity of the photograph to disrupt narrative expectations and their corresponding temporal linearity. In Cinema 2, Deleuze explains, "the crystal-image is ... the point of indiscernibility of the two distinct images, the actual and the virtual" (Cinema 2 82). The crystal image becomes the moment when "the actual optical image crystallizes with its own virtual image" (Cinema 2 69). This nexus of sensual visual experience with as-yet-embryonic visual potential engenders a radical temporal experience. The distinction between empirical and possible sights becomes uncertain, and this lack of certainty allows us to experience both the collapse and the disjunction of time in space; time, in effect, becomes freed from its dependence on space or movement in space. Deleuze explains, "what constitutes the crystal-image is the most fundamental operation of time ... time has to split itself in two at each moment as present and past." He concludes, "time consists of this split, and it is this, it is time, that we see in the crystal ... . We see in the crystal the perpetual foundation of time, non-chronological time" (Cinema 2 81). To become intimate with both past and present within a moment is to encounter the perpetuity of non-chronological time that is foundational to Deleuze's treatment of post-War cinema; we relinquish our investment in the past as a fixed reality to be recalled or forgotten, and instead produce new, unwritten stories, and create new relations between pasts, various actual presents, and virtual futures. While film offers a powerful medium through which to envision these new relationships between the past and as-yet-unseen futures, the photograph has been understood as a mere record of the past.

[18] This traditional approach to the photograph may ultimately be a function of the produced desire to mark fixed moments of history; if we can craft and sustain a stable and safe conception of the past, it provides us with a model through which to secure a static present and an organized future. This conception of photography is deeply rooted in the Enlightenment notion of organized knowledge emblematized by Boulée's Interior of a Library; it allows us to relate ostensibly fixed knowledges and events to other ostensibly fixed knowledges and events, ensuring that our findings, experiences, and even our stories are always already told and known. Sutton, however, prompts us to consider how photos might avoid such narrative predetermination and instead generate narrativity, which he claims is produced when "photographs project beyond the image into the past and into the future in an asymmetric, heterogeneous action. The images thus have a quality within them that emphasizes their connection to the viewer's memories, fantasies, and dreams" (143). This aesthetic theory of the photograph challenges the assumptions of Enlightenment thought, as it allows us to (re)connect images not to supposedly stable ideas or findings but to enduring experiences—i.e. sensations that remain active, volatile, or simply relevant. Sutton later adds, "any photograph that expresses a dominance of narration over narrative, in which the construction of image is more significant than subject matter, lend itself to the study of narrativity" (146). While the picture has been routinely credited with effecting a multiplicity of stories, the photo remains regulated and riddled by hackneyed tales and linear temporality; but if we can isolate and privilege a photo's production of sensations—and the aesthetic processes of this production—instead of the supposedly fixed content it represents, we can unburden the image of its documentary legacy and expose its Deleuzian potential.

Creative Potentialization and Photographic Becoming

[19] This issue of Rhizomes helps us to imagine how photography might generate new artistic, temporal, and narrative experiences that illustrate latent possibilities within and through actual sensations. As Sutton intelligently reminds us, "art is a creative process from actual to virtual, from real to possible, and from singularity to multiplicity," but he instructs, "this situation can only occur when organization is unforeseeable" (154). The artistic challenge to accept and even welcome the unanticipated is at best difficult. It requires us to relinquish control of empirical experiences of the world and embrace the rhizomatic productions of our sensations within everyday life; moreover, as viewers and scholars, we must remain open to seeing and appreciating a matrix of the actual and the virtual, and this too is an enduring aesthetic challenge for the study of photography. The camera's strong association with the realm of the actual may seem to limit photography's susceptibility to the domain(s) of the virtual, but this affinity for fact and the mundane may likewise be a key component of the art's Deleuzian potential. When we see and study photographs, we are understandably tempted to revert to hermeneutic models that reinforce narrative, figuration, and the temporal stasis of the image. To avoid—or, perhaps more accurately, to exploit and capitalize upon such a temptation—we must strive to see the photo, and not its clichés and narratives; we must certainly see the image as a source of creative possibility, but we must also remain artistically aware and critically self-conscious of both the image's ostensible objectivity and the conventional temporalities and significations that surround and seek to order it. The photo has been granted a power to capture and control life, the pure immanence that Deleuzian art strives to unburden and expose to new lines of flight. If photography can remain open, and encourage us to remain open, to the spontaneous dynamism of life, its unplanned energies, and the anticipation of the virtual, it has the potential to use and relinquish such documentary power—to image both the photographic actual and imagine photographic becoming.

[20] Deleuze, of course, highlights the creative power of becoming throughout his corpus. Near the end of Cinema 2, he writes: "Becoming can in fact be defined as that which transforms an empirical sequence into a series: a burst of series"—which he presents as "a sequence of images, which tend in themselves in the direction of a limit, which orients and inspires the first sequence (the before), and gives way to another sequence organized as series which tends in turn towards another limit (the after)." When art transforms our empirical sense perceptions into momentum, it produces energy, what Bergson famously theorized as élan vital, and Deleuze concludes that when this happens, we experience "a becoming as potentialization, as series of powers" (Cinema 2 275). It is becoming as potentialization to which I continually return in my own attempts to write about the Deleuzian aesthetics of photography. Photography is technologically ill-suited to represent time in the way that Deleuze theorizes the time-image of the post-War cinema; the still-image does not show Bergsonian duration or the direct-time image, but it has a unique capacity to document the actual while framing becoming(s) that envision momentum and gesture toward temporal perpetuity. Photography can indeed compel us to see and experience the sensations of the present, and while its representations may be fixed, they can also anticipate becomings replete with dynamic potentialization. Sutton eloquently discusses becoming as "the assembling and disassembling of entities by which we live our lives" (174). As we experience the immanence of life, we repeatedly collect and release creative, energizing, and territorializing forces, and as Sutton notes, "these are waves of becoming that intersect each other but, above all, intersect the culture that surrounds us" (175). Becoming is not merely an egotistical process whereby we grow or mature as individuals; rather, it is the phenomenon by which our dynamism interacts with the people, places, and sensations of our lives. Photography ultimately provides us with a valuable instrument through which to see, identify, and appreciate this dynamism; it can show us the sensations of our actual experiences—both in the present and the past—and invite us to accept our ongoing involvement in this immanence. And when a photo successfully points beyond its visual representation to a momentum of creative possibility, it allows us to embrace becoming as an ongoing reality of the actual world in which we live.

[21] Deleuze specifically invests becoming with political efficacy to create new kinds of realites, and in his studies of the cinema, he uses the concept to explain the distinct creative and political power of post-War film. Despite the desolation, displacement, and despair of the New Cinema, Deleuze insists that its "becoming is always innocent, even in crime, even in the exhausted life in so far as it is still a becoming" (Cinema 2 142). He does not highlight the importance of the presence of a new or rejuvenated people in the wake of the War, but rather the absence of a people—the missing people who are not representable through traditional aesthetic strategies or established modes of filmic storytelling. He explains, "the missing people are a becoming, they invent themselves, in shanty towns and camps, or in ghettos, in new conditions of struggle to which a necessarily political art must contribute." The elusiveness of "the people" in post-War film is, for Deleuze, an indication of immanent becoming, a site of political potency in which artists might "[contribute] to the invention of a people" (Cinema 2 217). He credits the New Cinema with the power to create new peoples as new potential becomings, especially in places that have been devastated; while the films often show desolation and disjunction as an actual reality, they likewise welcome the latent energy of life's dynamic creativity as virtual possibilities. Becoming is integral to the integration of the actual and the virtual; it allows artists and viewers alike to experience the volatility of the sensations within the present while simultaneously embracing the proclivities of the virtual. A Deleuzian approach to photography must theorize this creative potential of the still image. Photographic becoming cannot simply refer to idiosyncratic innovations or solipsistic artistic experimentation; it must maintain political efficacy in its documentations of the past, representations of the present, and visions of possible futures.

[22] I want to close this introduction by affirming that this potential for becoming is and has long been an integral component of photographic work. While the authors in this issue treat a wide variety of twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists who produce and reproduce Deleuzian intensities, I am a scholar of nineteenth-century culture, the era of photography's emergence. And photography, as is the case with many art forms, generates tremendous creative and political energy in its incipience. Talbot's groundbreaking work, The Pencil of Nature (1844-46), for example, helped to establish photography as an art in nineteenth-century Great Britain; this collection offered numerous examples of striking visual moments, supposedly captured spontaneously by the photographer at his ancestral home. "A Scene in a Library" (1844) is one such moment that offers us a seemingly simple and legalistic view of books on shelves. The titles are arranged for easy recognition, and we can clearly separate one book from the next. The volumes are carefully displayed, and the titles at the far end of the upper boards appear to function as bookends. We are visually invited to isolate a book, appreciate its decorative binding, and remove it. But this photo, like so much of early British photography, is marked by aesthetic experimentation that anticipates Deleuzian thought.[6] While we may are undoubtedly tempted to see Talbot's image as an artistic (and even political) descendant of Boulée's Interior of a Library, the photo poignantly manipulates such Enlightenment models of fixed and secure knowledge. Talbot's books are easily seen and accessed, but his framing disrupts our expectations for engaging and collecting information, as the books rest on what appear to be floating shelves that defy the logic of physics. There are no visible supports for these boards, and Talbot tempts us to imagine the continuity—indeed the perpetuity—of the shelves and the books. This is merely "a scene" in a library, a specific moment in time and space, but within it we find the presence of other moments—past and future possibilities for aesthetic and creative encounters with knowledge and sensation.

William Henry Fox Talbot, "A Scene in a Library" (1844)

Reproduced with permission from the Science and Society Picture Library,

the National Museums of Science and Industry, U.K.

[23] Talbot's image allows us to imagine and pursue these new possible experiences; it invites us to see the process of becoming as a part of both the aesthetic and the political experience of photography. And as Deleuze concludes, "Aesthetics can't be divorced from these complementary questions of cretenization and cerebralization. Creating new circuits in art means creating them in the brain too" ("On The Time-Image" 60). When we create new art, according to Deleuze, we likewise create new ways of thinking, new ways of relating with others, and new ways of encountering the world. Talbot's photo ostensibly frames the sources of information collected in Boulée's library, but his very aesthetic strategies illustrate the ongoing dynamism of knowledge and experience that Deleuze theorizes throughout his writings. For Deleuze, we will and indeed we must engage and produce new and changing sources of knowledge, and this ongoing process requires us to create and recreate sensations, relations, and concepts to avoid the routinizing effects of the laws, the church, and the state that haunt the legacy of Enlightenment thought. This is an intellectual and political necessity for Deleuze, and photography provides us with a creative means to embrace and challenge the figurative clichés, hackneyed narrations, and organizing principles of always-already known experiences. Ultimately, a Deleuzian aesthetics of photography is rooted not in the capacity of the image to record what has been known, seen, or experienced, but in its political potential to show us what might be, what has been forgotten, and what has not yet been imagined. We must read Deleuze against Deleuze to develop this Deleuzian aesthetics of photography, and this project is fundamentally Deleuzian because it offers us yet another opportunity to think and create anew.

[24] In what may appear to be one of Deleuze's most severe critiques of photography, he reminds us: "the most significant thing about the photograph is that it forces upon us the 'truth' of implausible and doctored images" (Francis Bacon 74). He indicts the mechanically-produced image for barraging us with truths that we know to be manipulated, perverted, or even territorialized, but his comment also suggests our recognition of this artifice; we know—indeed, we have known—that photos can be molded and modified, crafted and constructed, designed and developed to produce "truth." The photograph has been deployed to accomplish certain and specific ends, and it can likewise be redeployed to create alternative political ends. Deleuze acknowledges the artistic legacy of the photo as an objective marker and tool of Enlightenment systems of knowledge shown by Boulée's drawing, and he certainly cautions us about the danger of photographically-fabricated truths—truths that might inhibit our experience of sensations, deaden our sensitivity to creative energies, or even overburden life with figuration, narration, or clichés. But Deleuze's comment also reminds us of the capacity of the photograph to at once show the truth of our empirical experiences, reveal the fabricating effects of organizing structures, and generate new possible revisions or creative adaptations of actualities. As an art form, photography is clearly vulnerable to manipulation, and while this can distort the truth of immanence, it can also produce new kinds of sensations and truths still in the process of becoming. As a quotidian art form, moreover, photography remains susceptible to mundane revisions and deployments by ordinary individuals—individuals who create new kinds of knowledges, combine disparate images, and use charged captions to generate disruptive and random signification. The photo can show such virtual possibilities emerging from actual moments of ostensible objectivity, point to the potential for becomings, and imagine new virtualities that might never be framed or organized.

Works Cited

Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. 1896. Trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and Scott Palmer. Fifth Edition. New York: Zone Books, 1996.

Boulée, Etienne-Louis. Interior of a Library. c. 1798. The Morgan Library and Museum. New York, NY.

Conley, Tom. "A Politics of Fact and Figure." Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. 1981. Trans. Daniel W. Smith. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. 130-49.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. 1983. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

—. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. 1985. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

—. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. 1981. Trans. Daniel W. Smith. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

—. "Immanence: A Life." Pure Immanence: Essays on Life. Trans. Anne Boyman. New York: Zone Books, 2005. 25-34.

—. "Nietzsche." Pure Immanence: Essays on Life. Trans. Anne Boyman. New York: Zone Books, 2005. 53-102.

—. "On The Time-Image." Negotiations: 1972-1990. Trans. Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. 57-61.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Vol. II. 1980. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Kennedy, Barbara M. Deleuze and Cinema: The Aesthetics of Sensation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.

Novak, Daniel A. Realism, Photography, and Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

O'Sullivan, Simon. Art Encounters Deleuze and Guattari: Thought Beyond Representation. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Polan, Dana. "Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation." Gilles Deleuze and the Theatre of Philosophy. Ed. Constantin V. Boundas and Dorothea Olkowski. New York: Routledge, 1994. 229-54.

Porter, Robert. Deleuze and Guattari: Aesthetics and Politics. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2009.

Sekula, Alan. "The Body and the Archive." October 3 (Winter 1996): 3-64.

Smith, Daniel W. "Deleuze on Bacon: Three Conceptual Trajectories in The Logic of Sensation." Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. 1981. Trans. Daniel W. Smith. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. vii-xxxiii.

Sutton, Damian Photography, Cinema, Memory: The Crystal Image of Time. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Sutton, Damian and David Martin-Jones. Deleuze Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts. London: I.B. Tauris, 2008.

Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Talbot, William Henry Fox. "A Brief Historical Sketch of the Invention of the Art." 1844-46. Classic Essays on Photography. Ed. Alan Trachtenberg. Stony Creek, CT: Leet's Island Books, 1980. 27-36.

—. Henry Fox Talbot: Selected Texts and Bibliography. Ed. Mike Weaver. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1993. 59-63.

Tucker, Jennifer. Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Zdebik, Jakub. Deleuze and the Diagram: Aesthetic Threads in Visual Organization. New York: Continuum, 2012.

Zepke, Stephen. Art as Abstract Machine: Ontology and Aesthetics in Deleuze and Guattari. London: Routledge, 2005.

Zepke, Stephen and Simon O'Sullivan. Deleuze and Contemporary Art. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010.

Notes

[1] John Tagg, for example, explains, "what gave photography its power to evoke a truth was not only the privilege attached to mechanical means in industrial societies, but also its mobilization within the emerging apparatuses of a new and more penetrating form of the state" (61). Alan Sekula famously identifies photography as "modernity run riot," and argues that the camera "introduce[d] the panoptic principle into daily life" (4, 10). Damian Sutton is one of the few scholars who to extensively engage the Deleuzian potential of photography. In his engaging study, Photography, Cinema, Memory: The Crystal Image of Time (2009), Sutton explores how "the instantaneous photograph reverses our relationship to duration, a reversal that gives photography—both as optics and as imprint—its curious power." He adds, "with a photograph we are presented with an image that is static but that nonetheless can give a powerful sensation of time passing" (38).

[2] Stephen Zepke and Simon O'Sullivan's Deleuze and Contempoary Art (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010) provides numerous critical examinations of this Deleuzian notion of artist.

[3] We have seen several recent intelligent treatments of Deleuzian aesthetics that merit recognition. While Barbara M. Kennedy's Deleuze and Cinema: The Aesthetics of Sensation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003) clearly focuses on cinema, she provides an indispensable critical frame through which to conceptualize Deleuze and aesthetics. In addition, Elizabeth Grosz's Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008) is a vital text on this topic. See also Robert Porter's Deleuze and Guattari: Aesthetics and Politics (Cardiff: University of Wales, Press, 2009), Jakub Zdebik's Deleuze and the Diagram: Aesthetic Threads in Visual Organization (New York: Continnum, 2012), Stephen Zepke's Art as Abstract Machine: Ontology and Aesthetics in Deleuze and Guattari (London: Routledge, 2005), and Damian Sutton and David Martin-Jones's helpful sourcebook, Deleuze Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts (London: I.B. Tauris, 2008).

[4] In Matter and Memory, Bergson writes: "The whole difficulty of the problem that occupies us comes from the fact that we imagine perception to be a kind of photographic view of things, taken from a fixed point by that special apparatus which is called an organ of perception. ... But is it not obvious that the photograph, if photograph there be, is already taken, already developed in the very heart of things and at all the points of space?" (39).

[5] See, for example, Daniel Novak's Realism, Photography, and Nineteenth-Century Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008) and Jennifer Tucker, Nature Exposed (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

[6] In his account of the photograph, Talbot discusses what he terms a "rather curious experiment or speculation" (Henry 90). He details his artistic interests in chemical light rays captured by photographic techniques that remain invisible to human vision, and concludes by addressing a familiar metaphor, "the eye of the camera," which he claims could "see plainly where the human eye would find nothing but darkness" (Henry 91). Talbot imagines the power of the camera to make visible sensations that are physically unattainable to the human eye; he tempts us with new visions that neither Enlightenment thinkers nor Romantic poets could offer. And he concludes: "Alas! That this speculation is somewhat too refined to be introduced with effect into a modern novel or romance; for what a dénoument we should have, if we could suppose the secrets of the darkened chamber to be revealed by the testimony of the imprinted paper" (Henry 91-92). It is only here in his final comment that Talbot references books or the practice of reading that seem fundamental to the image. He alludes to the mysteries and bizarre happenings of Gothic romances, and notes how his proposed photographic experiments with chemical rays would disrupt or "refine" the sensational effects of novels. The camera, according to Talbot, has the potential to show us sights previously unseen by humans, but he also suggests the ramifications of such power; it could expose or make visible the wonder, beauty, and sublimity of art such as Gothic literature as mere material artifice. "A Scene in a Library" may serve as his attempt to reconcile this tension; the photo at once reveals its material fabrication and invites us to appreciate the sensational possibilities of vision and experiences that we do not yet see.