Seeing Immanent Difference: Lorna Simpson and the Face's Affect

Laurie Rodrigues

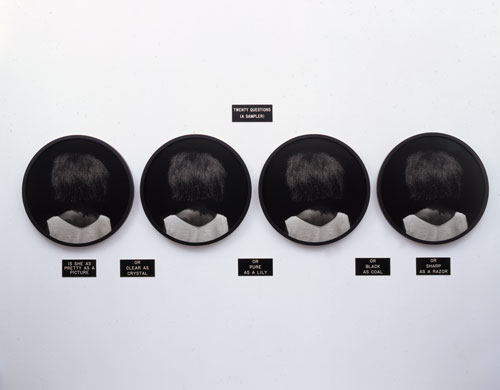

[1] I begin my intervention into Gilles Deleuze's relation to photography via a largely unexplored aesthetic terrain within Deleuzo-Guattarian studies: conceptual photography, and its implicit conversation with Deleuze and Guattari's concern for the inhuman dimension of the face. My lateral move into conceptual photography is, first, interested in thinking the Deleuzian other/ face in its very absence. What strikes the viewer when he/she is prohibited from seeing the other's face; and by extension, what transpires in the viewer when, in fact, the other's face is precisely the only thing that the viewer expects to see? Lorna Simpson's minimalist, conceptual anti-portrait, Twenty Questions (A Sampler) (c.1986) does not showcase a face; Simpson's subject confronts the spectator with the back of her head. Simpson's piece (and its underlying, racializing work) stands as the paradigm through which I read and re-frame the stakes of faciality on subjectivity and perception.

[2] One may consider Simpson's model in Twenty Questions a vehicle for the artist's enactment of the often contradictory values that photography seeks to problematize. Rather than taking a position within a dialectal construction, I will argue that Simpson's piece suggests that the 'incomplete' black female form conceptualizes an unsettling, virtual relation between the rational and the irrational. The absence of the face reveals the transcendent's appearance in actuality as that which is not interested or personal; rather, the transcendent appears as internalized difference, that which can only actualize itself in the human being in its differing from itself. I maintain that the back of the model's head, then, conceptualizes the foreclosure of her intensive life to the viewer; her apparent refusal cannot be grasped, and no amount of descriptive interpretation can represent it. [1] Here, we encounter Deleuze's primary problematic, with respect to the face/ Other: the face cannot form the foundation of an ethical relation to the Other; therefore, by preserving the model's face from view, we are disallowed from lapsing into habitual, interpretive work. The face is a false signpost, Deleuze implies; the back of a woman's head, then, is no less so.

[3] Speaking to this current of Deleuzian thought, my encounter with Twenty Questions complicates Deleuze and Guattari's conception of the face in A Thousand Plateaus (specifically, "Year Zero: Faciality"). "Year Zero" addresses Deleuze's preoccupation with the non-human, imperial dimension of the human face. Many thinkers have lingered over this Deleuzian conceptual concern, much as they have the Levinasian face—the supposed locus of humanity, understanding, and ethical exchange—the conceptualization of which stands in direct opposition to Deleuze and Guattari's. According to Levinas, the face is produced in humanity as the mechanism of signification and a modality for making sense of the body. The subject's interest, then, relies in the other's formal and content-oriented facial elements (e.g., skin color, bone structure, facial expression); by consequence, a face's meaning may only be retained by examining these intrinsic elements. In this way, Levinas's face is a material, pre-discursive universal. The nature/ essence/ humanity of the other is based upon the interdependence of facial form and content—the other should open the subject to the process of identification, in which the other represents to the subject some aspect of his/ her own self-conception.

[4] By contrast, Deleuze and Guattari's work on the face in A Thousand Plateaus presents a critique of the Levinisian "face of the other;" that is, Deleuze and Guattari approach the face's ontological inception and its function in constituting subjects. In "Year Zero: Faciality" they assert that the face is universal only insofar as it is a universal imposition, "overcoding" the body (a forceful, negative way of making "sense") and endlessly compelling us to over-determine our identities. Of course, one may predictably presume (adjacent to Levinas) that individual identities may exist within a milieu, amidst dominating forms of identitarian 'normality;' however, largely due to the face's problematically central role in identity determinism, Deleuze and Guattari argue that this is not the case. The face is a representative of humanity, but it is not confined to that humanity. Consequently, the face is an imperial machine, dependent upon precise social formations for its genesis and use. It overcodes the subject, functioning as the "black hole" into which individuality (and imperceptibility) is swallowed; it is the material traumatic thing, unsettlingly similar to the Lacanian Real (a.k.a., the "wall of the signifier," for Deleuze). In spite of this, however, individual subjects can escape the universality of the face, which Deleuze and Guattari argue is bound to a precise, Western European —that is, to the face of Christ.

[5] Levinas's concept, on the other hand, maintains that that commitment to the other exceeds our capacity to adequately respond; for him, ethics is not about life, but about something greater, transcendent. However, "Year Zero: Faciality" presents a critique of philosophy's 'ethical turn,' using Levinas's "face of the other" to examine how the face's domination fashions a troublesomely precarious, and even sentimentalized, other (Judith Butler's work in Precarious Life may come to mind). This results in the traumatic flattening of the subject. By contrast, according to Deleuze and Guattari, "the other person is the existence of another world"—and this "other world," of course, is neither subject nor object. Thus, the importance of the other/ face is conceptualized in a wholly different manner. First, for Levinas, the face is not thought of or experienced as an aesthetic object—as it is for Deleuze and my own work with Simpson. Rather, the unreflective encounter with the face is as the living presence of another person: as something experienced socially and ethically. For Levinas, then, living presence implies that the other person (i.e., genuinely other than myself) is exposed to me and expresses him/herself simply by being there as an undeniable reality (that is, an object) that I cannot reduce to images or ideas in my mind.

[6] Deleuze and Guattari, of course, situate the ontological origin of the face with the white, Western male—specifically, with European artists' renderings of Christ. They immediately posit the face as an image of the mind. Following this, they seek to assemble how "facialization" (the imposition on the subject to assume a 'face') was spread by white Europeans; in this way, we may use their critique of A Thousand Plateausto formally grasp the function of racism:

Racism operates by the determination of degrees of deviance to the White man's face, which endeavors to integrate nonconforming traits into increasingly eccentric and backward waves, sometimes tolerating them at a given place under given conditions, in a ghetto, or sometimes erasing them from the wall, which never abides alterity. (D&G 1987, 178)

As that which is doubled, (or, enacted before acted), Deleuze and Guattari maintain that the Levinisian face presents (i.e., fabulates) that which may only exist in discourse. It can never be actualized. Because of this, they assert that the face does not demand the humane treatment stipulated in Levinas's theory—formally, it cannot be a neat, automatic locus of recognition.

[7] Pervading language and overthrowing semiotic systems, the Levinasian face announces signifiers that language [re]produces; its imperialism threatens to defeat all other semiotic systems. The face, then, is not something which is 'seen' by the viewer, but rather 'witnessed'—Levinas's face, then, is a description, not a productive action. This posits the face as a surface system (at once pitted and smooth). My own discussion will betray a sense of social experience in the viewer's encounter with Simpson's model; foremost, in its complex re-working of Deleuze and Guattari's concept, I take on this absent face with its aesthetic/ political function in mind. Like Deleuze and Guattari, then, I engage with the face as a fundamental departure from Levinas's conception of its function.

[8] Simpson's art, including Twenty Questions, is referred to by the artist as "conceptual"—that is, expressing an idea, a generalization of properties common to a set of practices or objects (Ranciere 2009a, 72). Dissatisfied with such techniques (as in the domain of documentary photography, where Simpson got her start), Simpson's photography does not seek to re-present, in any faithful detail, physical, social reality. Rather, the photographic medium for Simpson is but a surface of equivalence between ways of meaning-making in different modes (i.e., looking/ reading). The medium of photography, then, is a conceptual space of articulation between these ways of meaning-making and forms of intelligibility which determine the way in which they can be conceived (Ranciere 2009b, 76). Twenty Questions consists of a series of four, identical photos of the back of a black woman's head; underneath the photos, five individual, inquisitive plaques are mounted—"Is she pretty as a picture," "or clear as a crystal," "or pure as a lily," "or black as coal," "or sharp as a razor." The resultant effect is an eerie, documentary-photographic array of questions (rather than explanations) accompanying so many non-representative/non-explanatory photographs. The model of the photographs is, it seems, heuristically dissociated from the questions printed on the plaques below her photograph; this presumed dissociation, of model from questions, is an example of a conceptual, reflexive twist, which functions only because the 'we' (i.e., the subject) are unable to see the model's face. While this structure creates a compelling, if simplified, visual conceptualization of abyssal otherness, it also calls into question the presumed identity of an implied viewer.

[9] Simpson's absent face is witnessed by the viewer, insofar as the dissociating plaques below the photographs enact the continual parallel (and/or confrontation) of reading and seeing. After all, how might the viewer qualify, or interperet, an array of photographs and plaques ("Is she pretty as a picture") such as Simpson's? What are we to make of the photographed woman: her posture suggests a refusal of conventional photographic portraiture ("or clear as a crystal"), while the photographs themselves are attended by so many plaques, as if labeling a case study or specimen ("or sharp as a razor")? Is she, after all, the subject of a photograph or a specimen—a thing? Our perception, or ability to perceive the model toward answering these questions, is overtaken by Twenty Questions' own reading of the infinitive imposition of the face. Without the face, how are we to answer these questions? The result of this dissociating process conjures in the viewer a memory deeper than memory—we witness the same photograph over and again in the company of variant text. By virtue of the photographs' repetition, the viewer may find him/herself reading the plaques below, from left to right, presuming they lead to an answer ('Is she, after all, "pretty as a picture"?'—we seek to know). This repetition is misleading, however—a formal trap to manipulate the viewer's affections. Thus, we find ourselves in a 'time' that has never been constituted as part of any 'present' state of affairs. Twenty Questions, then, as neither a perception nor a textual reading, betrays the 'that-ness' (i.e., otherness) of the image, affecting in the viewer an involution, from paralysis to rationalization.

[10] The viewer, however, will soon find that even rationalizations are difficult to come by here. Simpson is sensitive to the faith invested in social mores and artistic expectations, and she demonstrates this sensitivity, this understanding of the viewer's impulse, through her minimalist approach to presenting her model. The photographs of the woman are stripped of elements through which the viewer might build associations, or ultimately any rationalization of her meaning (or, identity). The model's hair and skin are almost as dark and matte as the photographs' background; absent from the photographs is the sheen-creating play of light, conventionally utilized to highlight, enhance, and (arguably) fetishize the gleaming richness of black skin (the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe may come to mind). The smoothness of skin is contrasted solely with the model's hair, which has not been subjected to/ altered by any regimen that may smooth it; that is, the woman's hair does not coalesce with any white, Western standards of 'beauty.' Thus, in lieu of light's enhancements, the model's dark skin (and hair) is solely emphasized by the white cotton shift that she wears; its solitary embellishments are two, barely-visible, white buttons that sit atop each of the model's shoulders. The cotton shift seems to fall loosely from the woman's narrow shoulders, as we can scarcely see the tops of her arms (and we cannot see anything below the model's shoulder blades). In its simplicity, one may wonder if this is not the shift's singular function—to create this sharp contrast of matte white on matte black.

[11] The model is matted within the frame, ostensibly part of/melting into the photograph's background. Twenty Questions, in this way, flattens the viewer's perception into a milieu; this milieu is a gap lying at the heart of perception, a 'not-yet-read' residing at the heart of the 'readable.' Here, the familiar, 'readable' scene metamorphoses into a 'that' (i.e., an object) onto which we are prevented from inscribing possibilities of meaning: emphasized by the plaques' dissociating affect, Simpson safeguards her model against the viewer's codification. The dissociated/ dissociating questions mounted below the photographs present (and even lampoon) the viewer's necessary recourse to interpretation; questions, extensive of their juxtaposed photographs, demark the perspectival process of qualificatory work. This meaning-making, or interpretive symbolic engagement, is wholly affective—a form of myth-making. This is an unrepresentable/irrational process instantiated in the spectator via his/her unconscious, socially-directed desire; this affective work is exerted (in the moment of transference from the 'seen' other) toward gentrifying the model's head to the level of a recognizable, fellow human. [2] Conventionally, the product of this work is the viewer's ability to identify with, and perhaps even feel empathy for, the recognizable image. However, Simpson does not allow the spectator to complete this affective circuit, through the plaques below the photographs, which amounts to a frustratingly missed relation—viewer perspective is, thus, rendered ineffectual. [3]

[12] The personalized interests of the viewer, Simpson implies, serve a greater, irrational (and arguably malevolent) desire: that of the late-20th century's American social formation (i.e., the 'meaningful' work of society building and cultural maintenance). This stands as the crux of Simpson's Deleuzian reconfiguration of the face and its subjectivity-construction: beyond our rationalizing attempts at meaning-making, in the moment of viewing, the model is also safeguarded against the viewer's face. As Deleuze and Guattari have taught us (contra Levinas), the work of the face is reliant upon this social formation, and the viewer, Simpson alludes, is likely a representative of the social formation's dominating forms of identitarian 'normality.' Simpson's model, then, seems to enact an uncanny 'understanding:' by facing us, she will ultimately fall prey to the (read: 'our') face's imposition, via its foundation in specific forms of Western, Euro-American figurations of knowledge: namely, the white, Western male. And by the same token, in her refusal to allow us to see her face, the model testifies to her/the other's resentment of this limiting and deterministic ontological origin (Deleuze 1986, 89). The transference of affect to the viewer takes place within this relational deadlock. Confronted with this problem—'What is there to see here, after all?'—the viewer is incapable of response. It is in this way, within the viewer's stultifying moment of seeing/judgment, that the production of affect (from images/plaques to viewer) twists back on him/her. Twenty Questions' reflexive twist, therefore, occurs in the model's/plaques' total refusal to cooperate, or yield in any way the wholeness and 'sense' which the interpretive viewer seeks.

[13] The back of the woman's head seems to demarcate symbolic excess, drawing out through hyperbole the totally unknowable status of the model to the viewer. It shows us that we can only guess at what she is, or who she is, on the most superficial level; which is to say, whether or not the spectator sees the woman's face is irrelevant to his/her ability to form a relation between the model and the questions below her image. The face, Simpson suggests (much like Deleuze), is but a fragment, a mask—an illusory, 'rational' crutch utilized in aiding dialectal formations. Problematically, these dialectal formations forcibly make of a person (or, a model) a position. Simpson points out to the spectator how the other's face is reduced to a mere 'that' in such oppressive instances of meaning-making (e.g., racism, sexism, classism and so on). The work of identity/identification, then, only tells us what someone is (an objectification), or who they are at the most superficial level; therefore, any 'politics' based on the interpretive, symbolic engagement of 'identification' forecloses the singularity of the other; this shuts down the space of ethical life.

[14] Simpson's faceless, bodiless female, then—beyond excessive—is an impossible figuration of femininity and deterministic, racialized associations. Precisely because she is rendered so minimally, so simplistically, the model goes to the end of everything that one may 'see' (by way of meaning-making) in the figurative, black female. By de-linking her model from any 'given' associations (familial/religious/economic/social), Simpson calls into question the imposing structure and function of determined, Western identity, in all its representative/repressive freightedness. Thus, through Simpson's manipulation of formal content and framing, her model's gaze will not meet the viewer's—we look to the figure for meaning, while the figure seems to gaze out into another realm, beyond the capacities of any interpretive mode. Recalling Deleuze and Guattari's conception of faciality, Simpson's piece betrays the complexity of relations which conspire in the appearance of the other.

[15] Simpson's extreme symbolization functions not to re-create any aspect of social/physical actuality, or a transcendental ideal, but to express the affect of unrepresentable concepts, creating and bearing upon social/ physical actuality. The model demonstrates the way in which 'rational' universals (e.g., personal interests, social roles, and so on) are carved out of a foundational, immanent irrationality. This conceptualization may call to mind the expository drive of Anti-Oedipus: Simpson's absent face undoes the order of 'realistic' representation, legitimizing an unconscious affect to be found in the relation between two (mistakenly exclusive) orders, the figural with the figurative, or the visual with the represented visible. [4] The result is a turn away from multifarious modes of meaning-making/ideal-maintenance, toward the possibility of an intensive visuality via the photographic image.

[16] On the level of the actual, we are offered photographs of a black female model, who is dissociated from the racializing, inquisitive phrases below her image; on the virtual level, organized around the precise power of the visible, Simpson disrupts the spectator's affective, interpretive circuit of labor. However, this apparent dissensus (as opposed to consensus) between the affective (or, virtual) domain and the actual is not the end of Simpson's critique—in fact, this dissensus operates as a perspective illusion in Twenty Questions. Rather than a discord between the two realms, virtual and actual, Simpson conceptualizes the actual as a qualified outgrowth (or, an expression) of the affective. Rather than Simpson's photographs constructing an automatically definitive, racialized position for her model, we see that the model's racialization is a product of a simultaneous play among unqualified, unrepresentable (read: social) forces.

[17] On the other hand, art criticism, as I have explored elsewhere, [5] traditionally fractures its investigation of the image into a series of domains which all seek some affectively-derived, mythic 'truth' (much in the same way Deleuze claims that philosophy does): whether implicitly or explicitly, epistemology, ontology, metaphysics, and ethics become discreet foci for each domain. What critics (and others) do not realize, however, is that their desire for conditions which allow for 'rational' meaning-making betrays their positive investment in the fundamental irrationality of their social formation. The social formation in which critics are invested is one which values generalization, simplification and distillation; in effect, that which can be interpreted and consumed is that which holds value. Personal identity (and its appended interests) is valued by the social formation inasmuch as its terms may be simplified to fit within its abstract machinations of desire-production. Without such terms the self collapses, feelings of lack set in. This structure is mirrored by Twenty Questions, as Simpson fragments the terms necessary for simplification and integration; Twenty Questions seems to expressly resist interpretation/engagement through a single domain. Twenty Questions' explicit subject matter deals with questions of racial construction, which (particularly in Simpson's high art world of the 1980s) are too often simplified or glossed over in favor of race's appropriation for consumption and profit.

[18] According to Deleuze, we may never find a home or ethical exchange in the face of the other (whether visible or not, I would argue); however, I argue, Simpson's piece constitutes the irruption of a crucial moment in which the viewer (though, perhaps only if willing) may finally sense him/ herself as thought. In her exploitation of the spectator's reliance upon interpretive symbolic engagement, Twenty Questions betrays the fact that these practices are widely unrecognized by America's mass society (Rodrigues 233). The inner workings of the late-20th century mainstream's relationship with race, Simpson indicates, is insufficiently (if ever) probed, while race's mythic (and often denigrating) associations hold precedence. In this way, Simpson adopts race as a field of convergence; race is a cracked surface upon which the affect-derived work of interpretation and consumption collide with the para-consistent function of personal identification.

[19] Without a meet-able gaze and/or face, Simpson's model betrays an intensive, auto-referential dimension; in her refusal to interact with the spectator, this auto-referentiality seems to be a point of liberation—an implicit, critical consciousness which Simpson's subjects, alone, seem to possess. Simpson's model, thus, gestures to the fringes of American society—a society which, ostensibly, offers her no goals or answers—remote from any 'community' orientation. If not vaguely cynical, beyond the bounds of mere representation/description, the images seem to offer up a real, interventionist critique of late-20th century American society. If presumed to represent anything, one might be tempted to suggest that Simpson's gaze-less, faceless model is representative of our time in history. Speaking, with Deleuze, to the importance of the one's intensive life, over and above external existence, Simpson's conceptualized femininity bespeaks a brand of introversion which has perhaps been forced upon the 20th century.

[20] In my use of the image as a method for inquiry, I have worked to betray the limiting, invested perspective of the viewing 'subject' within the meaning-making machinery of artistic discourse. Echoing Deleuze's own interdisciplinary approach to philosophy, Simpson similarly asserts that aesthetics, historicity, ontology and epistemology are not discreet 'critical' modalities, but are intimately related and interdependent. In fact, as we have seen, these primary movers of meaning-making are problematically shot through with personalized interest, which Simpson lampoons upon the surface of Twenty Questions. Thus, it is affect, as de-personalized force of immanence, which betrays how seemingly contradictory, apparently unrelated entities may be connected.

[21] The withheld face of Twenty Questions expresses a gap in the necessary conditions for the establishment of difference/sameness. And this, as Deleuze teaches, betrays both the viewing 'subject' and his/her perspective as inadequate; producing and manipulating affect, the faceless objet d'art insists—it becomes that 'something' in the world which makes us think. The diagram presented by affect does not merely describe its abstract relations, it performs them; and this performance may help us to understand the contradictory social and political structures, dynamics, and potentials of our intensive age.

[22] Simpson's photos also indicate foldings between levels of the affective enterprise; that is, they indicate the emergence of the 'rational' from a foundational irrationality. The portraits and their conceptual reverberations manifest the manner by which the photographs' concept of American identity layers and intertwines around the self-containing and the self-differing (which can only emerge in-relation). Comprising an immanent ethics, Simpson's photograph demonstrates that no entity (whether the 'I,' other, etc.) is ever absolute. Rather, all are elements of more encompassing frames of reference; all are products of abstract, qualificatory work. In turn, this work is also a product of the same background from which the entity emerges (not unlike Twenty Questions itself)—no product (not a theoretical approach, a photograph, nor the one's conception of the 'Other') can ever be more fundamental than the (affective, immaterial) process of its production. As expressions of the (arguably mythical) 'whole' from which they emerge, each entity and its appended affective process is ultimately a de-personalized perspective upon its own immaterial process of production.

Notes

[1] As a sidenote: even if we take the presentation of the back of the model's head, not as some communicative/associative 'refusal,' but as a performance, we may find that we can still draw the same Deleuzian conclusions and glean a distinctly Deleuze-reminiscent reaching toward immanence in the work of Simpson. The model's seeming antagonistic/negative relation to the viewer concomitantly speak to the politicized, social identities which she occupies as, at once, a black female model and an objet d'art. The work of l'objet d'art is presumed to be performative, as is that of the model; therefore, how can the woman under Simpson's employ effectively expose, or even engage, the hypocrites/the hypocrisy of her social formation? Such hypocrisies are precisely that which define the essence of her occupation: that is, exhibiting signs on the body of thoughts and emotions which are, presumably, not her own. Thus, while she may not betray any desire to be a representative figure, the logic of her attitude, her pose, seems to suggest that she cannot help but enact some form of representation—e.g., a performed refusal.

[2] To develop a critical discourse that circumvents a politics confined to the register of inside versus outside (read: tolerant/intolerant, 'good'/lacking), I adopt the Deleuzian connotation of "affect," specifically in its relation to his conception of "desire." That is to say, for Deleuze, desire consists of one's involuntary impulses/affects which have been assembled in a positive relation to (i.e., positively invested in) the social formation. According to Deleuze, then, one's desires are not her own, but are impersonal, unqualified forces of the social formation. Taken in this way, desire, affect and so on, can never be held in relation to lack. This formation thus asserts that the piece's asymmetries cannot denote lack, as some art critics have maintained; for Deleuze, lack only appears at the level of personalized interest because the social formation, in which one has already (involuntarily) invested one's desire, has produced that lack.

[3] One might even go so far as to assert that, in the moment of viewing Twenty Questions, the spectator may feel as though he/she is looking into a mirror showing the back of his/her own head (irrespective of the spectator's "racial" orientation). The para-consistent logic of Simpson's piece, therefore (whether described this way or as I have expounded upon it in the body text of this chapter), cannot merely be reduced to a symbolic "refusal" of the model to the conventions of portraiture. The inculcation of the viewer's own perspective within the work of Simpson's photographs, names a much more complex dimension, coexistent with interpretive symbolic engagement: personalized, affective labor.

[4] Here, I am adapting some remarks made by Jacques Ranciere in The Aesthetic Unconscious (c.2010; pp.62-65), with respect to a detail-oriented, Freudian method for the interpretation of art. He claims that the "insignificant" details of a work of art, according to this method, stand as a direct mark of "an inarticulable truth whose imprint on the surface of the work undoes the logic of a well-arranged story and a rational composition of elements" (63). For my purposes, I adapt this notion of the figurative/ visible (e.g., representational) detail and align it with the figural/ visual (e.g., the intensive).

[5] See Laurie Rodrigues. "SAMO as an Escape Clause: Jean-Michel Basquiat's Engagement with a Commodified American Africanism." Journal of American Studies 45:2, 2011 (Cambridge UP). 227 – 243.

Bibliography

Butler, Judith. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso, 2006.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Haberjam. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1986.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans., Robert Hurley, et al. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2008.

—. What is Philosophy? Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia UP, 1994.

—. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1987.

Flaxman, Gregory and Elena Oxman. "Losing Face," in Deleuze and the Schizoanalysis of Cinema. Ian Buchanan and Patricia MacCormack, eds. London: Continuum. 39 – 51.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Duquesne: Duquesne UP, 1969.

Ranciere, Jacques. The Aesthetic Unconscious. London: Polity, 2010.

—. The Emancipated Spectator. New York: Verso, 2009(a).

—. The Future of the Image. New York: Verso, 2009(b).

Rodrigues, Laurie A.. "'SAMO as an Escape Clause': Jean-Michel Basquiat's Engagement with A Commodified American Africanism." Journal of American Studies 45.2 (2011). 227 – 243. Also available at: « http://journals.cambridge.org/repo_A79qbRlU »

Rushton, Richard. "What Can a Face Do?: On Deleuze and Faces." Cultural Critique 51 (Spr. 2002). 219 – 237.

Simpson, Lorna. Twenty Questions (A Sampler). 1986.