Coming to know

Valerie Walkerdine

The green chair

[1] It sits in my bedroom now but it used to be in front of the gas fire in the dining room at home. It wasn't always green, but rather a 1950s pattern of yellow and red. It was in this chair that I learnt my notes by rote as my mother tested me. Growing up that's what I thought – what we all thought – like the Brain of Britain, cleverness was about remembering – having a brilliant memory and so mum and I both thought that the way to succeed was to remember my notes taken in lessons, word for word. Mum took it to heart so much that if I substituted 'and' for 'but', she sternly told me off.

[2] How could I ever get rid of the chair? It was my little place of learning. I and it were one or more appropriately I, it, my mother, the gas fire, the notes, the remembering, the feel of the chair, the exams, were one. In the world I inhabit now, we would call it an assemblage, but that is a universe away from that time, that chair.

[3] So, looking back, if all this was true, how did I get beyond the memory test of 'O' Levels at 16 to being a professor, a pathway that in my wildest dreams I could not have imagined or even wanted? But, that doesn't mean that I lacked imagination or a desire for something different, even if I imagined that to be a glamourous life in London and not a chair in the academy.

[4] In this paper, I look back through some of my work to think about how to address issues of the working class and higher education in today's university context. It is to the power of imagination that I turn again, though in a different moment and different way.

Marxism Today

[5] In the late 1970s/early 1980s, I attended a conference organized by the journal, Marxism Today, at which there was a session on class. Before the session, I met a male colleague (very upper middle class) and told him I was going to this session because of my interest in class. He said 'you – what do you know about class'? Then, sarcastically – 'oh yes, hidden injuries'...

[6] Of course we know of Sennett and Cobb's (1972) book from that period, The Hidden Injuries of Class, about upward mobility, but this comment, which I can still remember vividly 30 years later, attempted to put me in my place where understandings of class are concerned. At that time, discussions of class were largely the province of Left men, who did not, by and large, talk about themselves, though they often idolized 'working class heroes', who became the object of deeply romantic fantasies. Working class women, on the other hand, were often thought of pejoratively as conservative and reactionary. Though, not much later, all working class white people were thought of this way by a Left who blamed the white working class for voting in Margaret Thatcher.

[7] In 1985 I had first 'come out' publically as working class, having contributed to a volume of writing about girls growing up in the 1950s (Heron, ed, 1985). Looking back, I was terrified by this act and yet wildly angry at the same time. It also aroused a deep envy for girlhoods retold in the book that spoke of spending time in Ashrams in India and other exotic pursuits that required money, leisure and 'cultural capital'. My own rage spoke of the fear of being pushed right back out of the middle class academic and feminist world I had only just come to inhabit. However, having written this way was also freeing – there was no reason to feel such fear or to pretend quite so much (I say 'quite so much', knowing how much I was still frightened of middle class judgement and can be on occasions to this day).

[8] Valerie Hey (2006) credits Carolyn Steedman and me with inaugurating a particular kind of feminist work on class that works with the autobiographical. Indeed, educated working class women did indeed begin to write, often about themselves and I also made a documentary called 'Didn't she do well' (Metro Pictures, 1991) where a group of educated working class women talk about being educated. I want to discuss some of the reactions that this kind of work has provoked. Such an approach has been debated within academic feminism and more broadly, but I feel that the issue has not been put into context. The context that I am referring to is the Left male take on class as a heavy and hard (in all senses of the word) topic that is not addressed by any attempt to engage with the biographical, the experiential or the feminine. In this historical context, to offer an alternative is subversive and attempted to flesh out the understanding of the experience of classed subjectivity, beyond a set of romantic or reactionary fantasies about the lives of working class people. In the context of this paper, it is important to note that my experience of this work was of a double academic exclusion – exclusion by class origin and exclusion by gender as a working class woman, with a less romantic and heroic history than that invested in working class men by their middle class academic counterparts.

[9] Indeed, I often felt quite mundane and boring, since I could not offer an exciting and subversive radical trajectory through my early life, a life apparently championed by the middle class Left, for whom my life did not measure up. Yet, I was convinced of course, that it was ordinary everyday experience that needed to be understood. Thus, while feeling an initial surge of pleasure from my initial revelations of my class origins, the changing politics and academic fashions over the years, did not present an easy experience of the academy.

Getting over it?

[10] So, turning to the feminist academic debate, I want to think about Valerie Hey's 2006 paper 'Getting over it?', which develops an argument about writing about the self after being told at a Gender conference to 'get over it', when presenting a paper that mentioned her own classed subjectivity. Of course, I am sure that all of the writers in this issue share similar experiences if raising issues of their own classed subjectivity (as opposed to the class of research participants or Others being discussed), but how many times can an issue be trivialized by being told to get over one's experience? What Hey engages with is critiques by feminists about talking about the working class self, understood as confessional, revelatory, unsuitable realist.

[11] I want to explore what kinds of feelings, defences and experiences that might engage with. To be told to get over oneself is a criticism that one takes oneself too seriously – that the work is narcissistic, an accusation that has also been leveled at my own work. The critique that one should not be confessional of course also makes tacit reference to the work of Foucault and in feminism is often associated with the work of Judith Butler. Here, we are cast between the men, who take themselves seriously enough to be identified only with their ideas and the vulgarity (word chosen carefully!) of revealing one's autobiography, of reveling in one's pain, of being a victim. Childers (2002) argues that in the USA, it is not possible to know what someone else's (deep) background is when meeting others in higher education. I have to admit that this surprised me. As one participant in a research project in the UK said of class, 'you can spot it a mile off'. So, what does it mean to be spotted? If they know and we also know, how is it lived? And how does it enter the academic space? Does it result in silence, hiding, display, or any other of the myriad ways in which what is being felt makes itself felt?

[12] How does one ride the academic waves, the fashions, the highs and lows and stay true to a politics which engages with classed inequality, oppression and entry into higher education. One of the paradoxes of the current situation in Britain is that while there have never been more places in higher education, it has become more and more exclusive. Apart from Wales, which offers free education to its citizens and Scotland which offers reduced fees to Scottish residents studying in Scotland, the rest of the UK has very large fees unaffordable by relatively poor families. Thus, by default, elite universities in particular become largely middle class preserves, creating a situation differently formed but producing similar effects to the one that I graduated in in which the percentage of 18 year olds in higher education was 13. I have learned, however, over the years that writing and speaking publicly about class allows identifying students to approach me, to work with me. They often come to me because, like me, they have not felt 'at home' in the university. How do we survive in higher education on the one hand and keep fighting against oppression on the other?

[13] If, as Hey suggests, we are asked to 'get over it', who is doing the asking? Why should there be an objection to exploring classed backgrounds within feminist higher education? To understand this, I suggest, demands a historical excursion that notes the ways in which one class of women has been asked to regulate the other for a long time now. This regulative gaze, which has been operating in renewed ways in reality television shows (e.g. Wood and Skeggs, 2011), presents the working class other as a pathological version of the normal (read middle class) subject. Not a classed difference, but a normative difference, with class becoming flattened as normality/pathology. I suggest that it is within this context that the need to 'get over it', makes most sense. More than this, classed histories have also been extinguished in favour of a history of family pathology as in most studies of poverty and welfare and educational success, especially in the USA (Walkerdine, in press). Thus, the experience of successive generations of oppression and exploitation, its effect on the bodies of generations, is hardly considered, especially with respect to class (Walkerdine, op cit). This has the effect of making invisible the trans-generational classed experiences that cumulatively make up our present. It is in this context, that getting over it, seems to make sense, to suggest that we have to move forward, not look back, to become. And here, I can see the Deleuze Guattarian ideas being taken in vain! It is here that I think the idea that we must look forward to change has been misunderstood.

'I don't know who I want to be just for me'

[14] In my own academic career, things have changed considerably. In many ways, I do not feel the same as the young woman who first declared to the middle class world her class background, and yet it can still come and strike me afresh, in ways that I least expect. In the documentary, 'Didn't she do well', I often quote one participant, who says during the film, 'I know who I am in that place, I know who I am in the other place, but I don't know who I want to be, just for me'. The splitting off of two places and not knowing how to act in those places, but knowing how either to bring them together or to move on beyond them, is very familiar to me. The sense of having a way of being 'just for me' is I suspect, very familiar to middle class people, or at least, it might be fairer to say that they do not experience a sense of what they want to be as classed, in that it does not usually go against a grain, remove them from their family, and is, most likely, expected as an aspect of becoming an individual. But I think we can understand the 'just for me' place using the work of Guattari. Of course, while the fantasy of a place 'just for me' is a bourgeois one, it does allow us to think about the power of imagination – the sense that there could be 'something and somewhere else' and the way that this relates to the sense of who we are in the places that feel familiar to us. I wish to argue that we cannot 'get over it' without understanding and engaging with complex affective issues.

[15] So, what I would like to offer to an understanding of the relevance of biographical class to higher education is an understanding of the complex affective pathways that need to be engaged to think about the possibility of change.

A performative model of transmission?

[16] I want to ask if we can approach the affective relations of class performatively as a project for higher education. Making imaginative leaps by performing, not in the sense that the exterior, performance of class, is all that there is, but covering a gap – where there once was silence let there be speech. Where there once were images of nothing (no culture), let there be performances.

[17] I have recently been working on class and intergenerational transmission as well as paths of working class young women to higher education. An understanding of intergenerational transmission for me is not about establishing the hopeless pathology of working class families but an understanding of the place of history in the making of affective experience and its transmission across generational boundaries.

[18] I have written about this in a number of ways – from reality television to de-industrialisation, from the personal family narrative to the unspoken transmission of bodily affect.

[19] In the remaining sections of the paper, I will briefly explore these aspects and then go on to think about how Guattari's work might help us engage with the possibility of change for working class students in higher education.

[20] I explore the proposition that any understanding of class today must engage not only with its narrative history but also with its affective history – i.e. that which is transmitted by the historical experience of class in all its forms. If we deny this, we are not understanding the present of class. This suggests an entirely different approach to the topic than that which is presently understood.

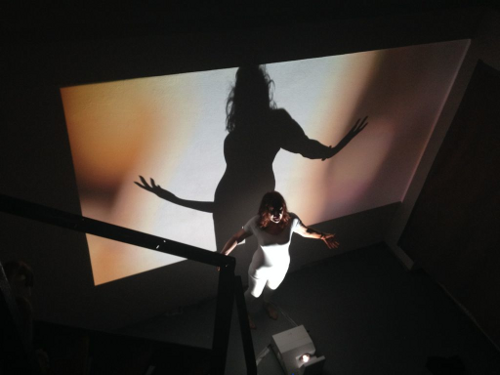

[21] A few years ago, I undertook some research in a de-industrialised steel community in south Wales, the former heartland of the British coal and steel industry (Walkerdine, 2010; Walkerdine and Jimenez, 2012). The study uncovered the complexity of a history of chronic insecurity in which the steelworks had closed or had lay-offs many times in its 200 year history, creating a climate in which nothing in the working environment could be understood as stable, with many threats such as the workhouse. I began to ask how might it be to live this situation, year after year, generation after generation? A number of practices emerged, such as a closely knit fabric of community in which people looked after each other, cared for each other in the absence of other resources. In addition, the trade union movement grew strong and militant. These were crucial to survival but in addition, the figure of the strong, proud steelworker was crucial to the community – a figure who could withstand the harsh and dangerous conditions of iron and steel work and who provided an iconic strong resistant masculinity. I argued that a strong division of labour made sense in this context and should not be thought of as sexist in any simplistic ahistorical terms. Rather, it had consequences that were detrimental to women, but it had to be judged by the necessity of history and not in terms of current values. At one level the figure of the steelworker acts as a fantasy – the strength needed to withstand capitalism, harsh and dangerous conditions, to ensure historical and family continuity. But at the time of the final closure of the works, something happened. The union could not withstand the onslaught and had to give up the fight to keep the works open. I believe that this was central to the devastation of the fantasy and terrible loss that followed. Indeed, most of the men could only find work that paid much less well and this alone changed the domestic division of labour, with many wives going out to work. Indeed, so much so that it was they not the men who brought in the wages even though many of them insisted on still treating their men as the family 'breadwinner'. The complex gendered entanglement could be understood as a way of coping with the changed reality and the complexities of the loss of the fantasies of continuity of the strong steel men that accompanied the possibilities of continuity in a world that was far from safe. I want to argue that this loss shattered a set of modes of being that had managed to keep people safe after a fashion for two centuries. These modes of being were strongly embodied – from the cultivation of the male body to the continuity of marked sexual and gender difference, but we might also suggest that the lack of safety might also always be bodily present even in its experience of having kept such a terror at bay.

[22] The next generation of young men has never known the steelworks, which closed in 2002. They long for heavy manual work, but mostly find low paid service work like stacking supermarket shelves, pizza delivery and contract cleaning. Their accounts reveal how much distress is being communicated to them and by them. Stories of fathers refusing to talk to sons in shaming delivery uniforms, of women cleaners ridiculing young men and young men in turn trashing shelves stacked by others as a sign that this is a woman's job. How much unspeakable pain is communicated in such actions? How much they tell us that nothing is resolved even as talk of phoenixes rising is delivered as public discourse. How does that lack of resolution sit? How is it marked on the old and young alike? How might it be resolved? What is the possibility of its future without understanding its past?

[23] I am thus arguing for an understanding of the complexities of what is transmitted intergenerationally. The complex affective histories which these case studies reveal.

[24] When considering the present of class, it is these embodied histories that are central in tandem with discursive histories of classification. I suggest that they create our complex present of class as it is today.

[25] Another context in which we could understand this phenomenon is by examining the media. I explored the phenomenon of reality television shows, by thinking about the issue of shame. I argued that shame and the working class female body was a significant issue from the Victorian period onwards (Walkerdine, 2011). The issue of being shamed and avoiding shame in relation to sexuality were major issues, widely documented. By looking at the British television programme, 'Ladette to Lady', which featured British and Australian working class young women sent to a kind of finishing school as kind of latter-day Eliza Dolittles, the women are taught to have manners and to serve the wealthy. Although in the context of the programme, it is presented as possible for the young women to move into that world, on screen they are treated badly sexually by upper class men (unremarked on in the show) and the skills that they are taught are ones involving what we might call 'hospitality'. The reform of working class young women who are supposed to be ashamed of themselves is not confined to this programme. It is offered in so many British television programmes that run the gamut of issues from parenting to keeping the house clean. Shamed and in need of reform or unrepentant and incorrigible as in drama series like 'Shameless', that features a family on a public housing estate. I suggest that in this way too we can understand the provenance of the affective experience and cultural practices of class/ification across generations, allowing us to fully engage with the legacy of class from the past as it operates in the contemporary present.

Ladette to Lady

Performing the intergenerational transmission of class

[26] In the Steeltown work, we could say that the unnamable losses were acted out or performed in the relations between father and son, women and male cleaners, for example. We could add that bit parts are played in the drama of history by pizza delivery uniforms, mops, supermarket white coats, steelworker donkey jackets. I was very encouraged in this way of thinking by a number of bodies of work. The work of the psychoanalyst Francoise Davoine, who deals with intergenerational experiences of war, genocide and psychosis, really captured my imagination. In one important paper (Davoine, 2007), she discusses a clinical session with a woman who believed that her mother was in the Resistance in the Second World War and was taken by the Nazis. Davoine artfully describes the way in which the truth of what happened is performed through the affective relation of analyst and patient, a situation that only comes to make sense on reflection. In the session, the patient accuses the analyst of experimenting on her and likens her to Hitler or Mengele. The analyst, for her part, experiences an old Jewish woman come to accuse her. It is through that experience that they both first begin to understand that the mother was taken not because she was in the Resistance but because she was a Jew. What interests me here as in the Steeltown example, is how the unspoken history emerges obliquely and performatively. The consulting room becomes a performance space in which that which is at first experienced bodily, affectively, can be acted out. When it has been performed, it can begin to move from what the analyst, Christopher Bollas calls the 'unthought known' (Bollas, 1987), to being able to be known consciously.

[27] In my own work, I also work performatively and with images. I began to work performatively with an image of my maternal grandmother, both performing her myself and asking others to perform her. I learnt a great deal from this (Walkerdine, 2014). But taking this work forward, I researched the records that related to my grandmother's life and found complex, unexpected and unspoken issues relating both to her and to my mother's (as it turned out, illegitimate, but hidden), birth. In visually documenting what I uncovered, I became dissatisfied with this approach. I decided that I needed to work the other way round, with what my body spoke to me, to understand through the bits of the story I knew and the use of my imagination, to engage with the affective experience of growing up with my mother, father and grandmother. This began with photographed images of me in bandages, recalling my mother's eczema, and progressed to the devising of a video installation and performance. In the latter, I began with a scenario that never happened but which seemed to capture a strong feeling, that of me in a room with the three of them and a drone begins to fill the air until it becomes deafening and unbearable and I, as a small girl, shout stop. Shouting stop has the effect of breaking apart the situation so that all the participants can be released from the stifled and overwhelming anxiety that fills the room. This work became a video with dancers, set in the underworld, which the girl enters to understand why she feels only half alive. In front of the video, I performed three songs which were very evocative for me during my growing up. The first 'two, Abide with me' and 'Keep right on to the end of the road' are very associated with war and death. The first was played on the piano by my grandmother and the second reminds me a great deal of my mother's need to 'soldier on'. Performing them, I became viscerally aware of the huge place of two world wars in the experiences of my mother and grandmother. I was filled with their experiences of death and struggle in a way that I could not have ever experienced from writing or indeed from simply listening to the songs. The third song, the Donkey Serenade, brought back shameful memories for me of being told by my mother to tell the music teacher at school that she preferred this to Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture, which I had brought home from school as a record. Yet on listening again to the song, I understood how happy and light it was, how it spoke of romance and how it showed me the playful and romantic side of my mother that I had not been able to see. Performing it brought a lightness back. To perform, I used a technique developed by the Roy Hart Theatre (http://www.roy-hart-theatre.com) to use an extended vocal range to convey a wide variety of affective states.

M/Other, photographic print, Valerie Walkerdine, 2013.

'The maternal line,' still from video installation and performance, Valerie Walkerdine, as part of the exhibition 'Alternative Maternals', Lindner Project Space, Berlin, 2014.

[28] I am using this example to get across the idea that uncovering facts and narratives can do so much, but engaging with those facts in a way that facilitates the possibility of change requires an engagement with the embodied and affective. That is, we learn certain facts – shocking as they are but that story does not, in and of itself, free us. So we need to start from the now – what accounts for these feelings? Of course we cannot always know and have to imagine.

[29] It is in this context that I have found the work of Guattari extremely helpful. That Guattari made ethico-aesthetic practices central to his practice, is crucial for what I am trying to explore. Unlike some critiques of psychoanalysis using Deleuze and Guattari as a base, who seem to think that being 'forward looking' is a substitute for working through the past, Guattari's actual position is much more sophisticated than this. I have explored this in a number of publications (Walkerdine, 2011, 2012 and 2014). What he said in The Three Ecologies is that 'the unconscious remains bound to archaic fixations only so long as there is nothing which engages it and can form an investment in a future.' It is to how that future is engaged that he devoted much of his work. Working in the 1980s, with the family therapist Mony Elkaim (Elkaim, 1997), he gained a great deal from the staging techniques of family therapy in which family members (e.g. a father and son) might be paired in a novel task, designed to get them to see their relationship and situation in a new way. The results of this in Guattari's published writings in English are most visible from the work in Chaosmosis (Guattari, 1992) where he presents the example of being a cook for the day, putting the patient in the clinic in a novel situation to see if a new way of being in the world might emerge, given the proviso that nothing was certain or predictable. This has to be understood within the framework of his concept of the Schizoanalytic Cartographies, devised in collaboration with Elkaim. The fourfold framework through which to understand the unconscious is extremely helpful for thinking about the relation of the past to the present and future and also for understanding what is at stake in being able to face the possibility of change in the future without collapsing into an anxiety state.

[30] As Brian Holmes notes, the cartographies are formed of 'a series of diagrams' relating to 'four domains of the unconscious, four inter-related varieties of experience, that overflow the ego to constitute an expanded field of trans-subjective interaction' (Holmes, 2009). Holmes notes that '[t]he four divisions of the diagram deal with ... existential territories, material and energetic flows, rhizomes of abstract ideas and aesthetic refrains' translating as 'the ground beneath [one's] feet, the turbulence of social experience, the blue skies of ideas and the rhythmic insistence of waking dreams.' Holmes describes the way that kinds of experience are linked into

a cycle of transformations, whose consistency and dynamics make up an assemblage (individual, family, group, project, workshop, society etc). The ultimate aim in the relation with each assemblage was to arrive at "a procedure of 'automodelling,' which appropriates all or part of existing models in order to construct its own cartographies, its own reference points and thus its own analytic approach, its own analytic methodology." (Guattari, F. qtd. in Holmes, 2009)

The Existential Territory is, says Holmes, the place in which language collapses and we are confronted by skin and sensation – the place of sensory experience, of affect, thought about specifically by object relations work on infancy (see Walkerdine, 2010). So we have to think of the way in which we inhabit a space and time, through our affective and sensory experience of it. This could be a neighbourhood, a home but it could also be the experience of a "bottomless black hole" (Holmes, 2009). According to Holmes, it is the experience of pacing, wandering, finding one's territory. In this, he makes a reference to Situationism in which Guy Debord (1995) worked with the idea of the drift in which we might understand the psychic geography of a place through our actual wandering through it. Central to Guattari's view is the way in which our territories attempt to mark out our own boundaries in an existential sense. It is this issue which is crucial because our existence as separate beings in object relations terms is understood by reference to an experience of primary process which allows us to feel held and as though we have a continuity of being (Bick, 1987; Walkerdine, 2010).

[31] How do we mark out ourselves, our space, how do we come to affectively mark the boundaries of our affective bodies? This is the place, he says, in which subjectivity emerges.

Territories of existence drift in relation to each other like tectonic plates under continents. Rather than speak of the "subject", we should perhaps speak of components of subjectification, each working more or less on its own. This would lead us, necessarily to re-examine the relation between concepts of the individual and subjectivity, and, above all, to make a clear distinction between the two. Vectors of subjectification do not necessarily pass through the individual, which in reality appears to be something like a "terminal" for processes that involve human groups, socio-economic ensembles, data-processing machines etc. Therefore, interiority establishes itself at the crossroads of multiple components, each relatively autonomous in relation to the other, and, if needs be, in open conflict (Guattari, The Three Ecologies, p. 25).

Thus, the basic building block for thinking about subjectivity within Guattari's work is the concept of existential territories. If we take the above quote, we can see that vectors of subjectification passing through individuals is very close to the Foucauldian notion of subjectification (Henriques et al, 1984) and the understanding of subjectivity as a relay point or vector of positions discussed by Henriques et al and Walkerdine (2007).

[32] For Guattari, the subject is a terminal for processes that involve human groups, socio-economic ensembles, data processing machines. So, what we see here is that these groups, ensembles and machines are what is primary and interiority is what establishes itself as at the crossroads of these, which may sit alongside each other or be in conflict with each other. Subjectivity is an effect of these processes and not its cause. Guattari invites us to think this assembled subjectivity via far earlier processes connected to embodied infantile sensory experience.

[33] The use of psychoanalysis in relation to this proceeds in a kind of phenomenological way but without "the systematic reductionism that leads it to reduce the object under consideration to a pure intentional transparency" (Guattari, The Three Ecologies, 2000 p. 25).

[34] Elkaim's work focuses on how certain ways of relating brought into the system by its members from the past, when taken together, can produce a certain stuckness and so an inability to move forward. We can see here that Elkaim credits Guattari with bringing in the importance of change and transformation within the future as opposed to understanding change as simply produced through a working through of past internal conflicts as would be classically psychoanalytic.

[35] As Holmes explains,

each zone of a four-fold map is understood not as the definitive structural model of an unconscious process, able to render its truth or meaning, but rather as a meta-model, a way of perceiving and perhaps reorienting the singular factors at play. "What I am precisely concerned with," Guattari wrote, "is a displacement of the analytic problematic, a drift from systems of statement (énoncé) and performed subjective structures toward assemblages of enunciation that can forge new coordinates of interpretation and 'bring into existence' unheard of ideas and proposals." (Holmes, 2009)

The four divisions of the diagram deal with existential territories, material and energetic flows, rhizomes of abstract ideas and aesthetic refrains. This translates as the ground beneath one's feet, the turbulence of social experience, the blue skies of ideas and the rhythmic insistence of waking dreams. These kinds of experience are linked into a cycle of transformations , 'whose consistency and dynamics make up an assemblage' (individual, family, group, project, workshop, society etc).

[36] Guattari's unconscious has these four dimensions, each of which relates to the body in a different way. The ground beneath one's feet relates to holding and orientation (Meltzer, Tustin, Hauzel, Anzieu); the turbulence of social experience relates to modes of interacting or relationality; the blue skies of ideas could be related to the importance of thinking, as in Bion's K and –K and the rhythmic insistence of waking dreams relates to the distinction between fantasy and reality. So what we have here is an emotional or affective geography. What we need to understand is the way in which the adult's affective geography is built upon the unspoken geography of infancy—that is the looks, the sounds, the feel of a mother's body and so forth, are then built on and recalled in the geography of the adult, which itself relies on sensation, feeling, memory.

[37] The ultimate aim in the relation with each assemblage was to arrive at a procedure of 'automodelling', which appropriates all or part of existing models in order to construct its own cartographies, its own reference points and thus its own analytic approach, its own analytic methodology" (p9).

The Existential Territory is, says Holmes, the place in which language collapses and we are confronted by skin and sensation – the place of sensory experience, of affect, thought about specifically by object relations work on infancy (see Walkerdine, 2010). So we have to think of the way in which we inhabit a space and time, through our affective and sensory experience of it. This could be a neighbourhood, a home but it could also be the experience of a "bottomless black hole" (Holmes, nd). According to Holmes, it is the experience of pacing, wandering, finding one's territory. In this, he makes a reference to Situationism in which Guy Debord (1995) worked with the idea of the drift in which we might understand the psychic geography of a place through our actual wandering through it. Central to Guattari's view is the way in which our territories attempt to mark out our own boundaries in an existential sense. It is this issue which is crucial because our existence as separate beings in object relations terms is understood by reference to an experience of primary process which allows us to feel held and as though we have a continuity of being (Bick, 1987; Walkerdine, 2010).

[38] How do we mark out ourselves, our space, how do we come to affectively mark the boundaries of our affective bodies? This is the place, he says, in which subjectivity emerges.

Territories of existence ...drift in relation to each other like tectonic plates under continents. Rather than speak of the "subject", we should perhaps speak of components of subjectification, each working more or less on its own. This would lead us, necessarily to re-examine the relation between concepts of the individual and subjectivity, and, above all, to make a clear distinction between the two. Vectors of subjectification do not necessarily pass through the individual, which in reality appears to be something like a "terminal" for processes that involve human groups, socio-economic ensembles, data-processing machines etc. Therefore, interiority establishes itself at the crossroads of multiple components, each relatively autonomous in relation to the other, and, if needs be, in open conflict. (The three ecologies, 25)

For Guattari, the subject is a terminal for processes that involve human groups, socio-economic ensembles, data processing machines. So, what we see here is that these groups, ensembles and machines are what is primary and interiority is what establishes itself as at the crossroads of these, which may sit alongside each other or be in conflict with each other. Subjectivity is an effect of these processes and not its cause. Guattari invites us to think this assembled subjectivity via far earlier processes connected to embodied infantile sensory experience.

The use of psychoanalysis in relation to this proceeds in a kind of phenomenological way but without "the systematic reductionism that leads it to reduce the object under consideration to a pure intentional transparency" (Guattari, Three ecologies, 2000 p25).

His concept of the Incorporeal Universe is a way of thinking about the possibility of moving from known territories into the creative but frightening space of the unknown, an unknown which is not yet embodied but can be created. It is how to manage that without succumbing to an annihilating anxiety, a need to re-territorialise, to effectively go back to the place that feels safe and known, which is the task he sets out to explore, both in therapeutic and political terms.

[39] In stressing the issue of the possibility of being safe of feeling 'at home' in one's skin, in one's territory and still changing, he is proposing a way of thinking and working affectively and imaginatively that may work as a possible approach to the opening up of higher education to those othered groups who do not feel safe.

[40] Beyond this, I want to propose an approach which brings a number of elements together. That is, the historical and cultural work of understanding the specificities of classed experience in a variety of locations, the legacies of that experience into the present, the governance and disciplining of working class subjects and communities across that historical period and how this works in the present, the cultural and media spaces in which such modes of regulation are popularized and how they are affectively experienced, as well as the positive energies and affects, the real things built that came from the attempts to work positively within the historical limits to build strength. To engage with these issues in a serious way as a project of research and pedagogy would be an important undertaking that might facilitate a coming to know that could be transformative.

[41] Can we begin to make this happen?

References

Bick, E. (1987). The experience of skin in early object relations. Reprinted in Collected Papers of Martha Harris and Esther Bick. Clunie Press.

Bollas, C. (1987). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unthought known, London, Karnac.

Childers, M. (2002). 'The parrot and the pitbull': trying to explain working class life. Signs, 28, 1, 201-220.

Davoine, F. (2007). The characters of madness in the talking cure. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 17, 5, 627-638.

Debord, G. (1995). The society of the spectacle. New York: Zone Books.

Elkaim, M. (1997). If you love me, don't love me. New York: Jason Aronson.

Guattari, F. (1989). The three ecologies. London: Continuum.

Guattari, F. (1992). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Sydney: Power Institute.

Hey, V. (2006). 'Getting over it?' Reflections on the melancholia of reclassified identities, Gender and Education, 18, 3, 295-308.

Henriques, J. et. al. (1984.) Changing the subject: Psychology, social regulation and subjectivity. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Heron, L. (1985). Truth, dare or promise. London: Virago.

Holmes, B. (n.d.). Guattari's schizoanalytic cartographies, or, the Pathic Core at the Heart of Cybernetics. «http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/02/27/guattaris-schizoanalytic-cartographies/» (accessed 30.9.14)

Sennett, R. and Cobb, J. (1972). The hidden injuries of class. New York: Vintage Books.

Walkerdine, V. (2010). Communal beingness and affect: An exploration of trauma in an ex-industrial community. Body and Society, 16, 1, 91-116.

Walkerdine, V. (2011). Neoliberalism, working class subjects and higher education. Contemporary Social Science, 6, 2, 255-271.

Walkerdine, V. (2013). Using the work of Felix Guattari to understand space, place, social justice and education. Qualitative Inquiry, 19, 10, 756-764.

Walkerdine, V. (2014). Felix Guattari and the psychosocial imagination. Psychosocial Studies.

Walkerdine, V. and Jimenez, L. (2012). Gender, work and community after deindustrialization: a psychosocial approach to affect. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Walkerdine, V. (2014). The maternal Line, Artist's Book, Alternative maternals. Lindner Project Space, Berlin, August.

Walkerdine, V. (in press). Transmitting class across generations. Theory and Psychology.

Wood, H. and Skeggs, B. (2011). Reality television and class. Basingstoke: Palgrave.