Hidden operations: Hermine Freed's video work ART HERSTORY

Nina Schjønsby

[1] Hermine Freed's Art Herstory (1974) is a pioneering video work, though it is probably unfamiliar to most people today. Through a self-critical gaze, the video highlights the processes of historicisation, its more or less arbitrary inclusions and omissions, its hidden operations. With the passing years, Art Herstory has itself succumbed to precisely these processes, turning it into a good illustration of the same marginalisation which the video seeks to put up for debate.

[2] In Art Herstory Freed uses montage to intervene in canonical works from the history of Western art. She disrupts these works, which range from medieval illuminations to modernist paintings, by situating herself and other figures within them, while at the same time turning a critical eye on the concealed processes of historicisation. In both its title and its content, Art Herstory makes clear reference to a feminist agenda and is thus a child of its time. The spread of the video medium occurred simultaneously with the rise of the second wave feminist movement in the United States. Video as an art form was still undefined, and as such it allowed female practitioners to play a part in laying its foundations and shaping a frame of reference. However, many of the artists who were active in those years now occupy only a marginal position in art history. Freed (1940-98) is one example. She was represented in many important group exhibitions and in leading anthologies about the medium during the 1970s. In 1972, for example, Freed was invited to contribute to the touring exhibition "Circuit: A Video Invitational," that featured fifty-two video artists and was arranged by the Everson Museum. She participated also in "Art Now: A Celebration of the American Arts" at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (Washington, D.C., 1974), in "Women in Film and Video Festival" at The State University of New York at Buffalo (Buffalo NY, 1974), in "Projected Video" at the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, 1975) and in 1977, she took part in "Documenta" in Kassel (Germany). She has now been all but written out of history. Freed is ignored both in synoptic works on the history of video art published in the 1980s and later, and in the feminist exhibitions of the 2000s that aimed to incorporate marginalized artists. For example, she was surprisingly not included in the large feminist touring exhibition "WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution" (2008/2009), curated by Cornelia Butler.

Positions and premises

[3] Art Herstory is commenting on the historicisation process, its mechanisms and hidden operations. Let's have a look at some theoretical positions and perspectives from the 1970s and later on in which established art history writing is criticized. Important early feminist texts from the 70s included Linda Nochlin's classic "Why Have There Been no Great Women Artists?," the early issues of The Feminist Art Journal (1972-), and some years later, Lucy Lippard's writings on contemporary women artists in From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art (1976), Griselda Pollock's re-readings of canonical works from art history, and the magazines Heresies and Chrysalis (both launched in 1977, in New York/Los Angeles, and produced by feminist collectives). By addressing the absence of women in art history Nochlin opened a discussion on how to approach feminist historicisation. According to Nochlin it was important to shed light on female artists and their work, but searching for female Michelangelos was by no means enough. One of the key insight Nochlin's essay offered was, in the words of art historian Moira Roth, that "this additive approach does not function well." Adding women to an established art history leave the disciplinary boundaries and methods intact. These feminist texts call for an alternative art history defined by other premises than the old canon of male geniuses.

[4] Art historian Griselda Pollock has been an important feminist historiographer, with her focus on social and ideological context. Like Roth, she stresses that a paradigm shift in art history involves much more than adding women and their history to existing categories and methods. "We have to find wholly new ways of conceptualizing what it is we study and how we do it," Pollock writes in Vision and Difference, in 1988. She focuses on the historicisation itself, as Freed does in her video work. The agenda for analysis is not just the history of art—i.e. the art works of the past—but art history as a discipline. With reference to Michel Foucault, Pollock is concerned about the discourses that shape our definitions of what art history can be about, as she states: "...in the interconnections, repetitions and resemblances a prevailing regime of truth is generated providing a large framework of intelligibility within which certain kinds of understanding are preferred and others rendered unthinkable." Pollock stresses that art history is not just indifferent to women; it is a masculinist discourse, party to the social construction of sexual difference. It is therefore necessary, she underlines, to reread the texts of art history and put the position they were written from under scrutiny. A contextual reading, where issues about gender, class, and race are addressed, is crucial in the feminist rewriting of art history. The art works, or the art practices, must be seen as part of a complex context of social issues, and a large interconnecting system of museums, educational systems, galleries, family politics, art magazines, just to mention a few relevant institutions. Pollock underlines that we have to analyze what any specific practice is doing, what meaning is being produced, and how and for whom.

[5] The argument put forward in this essay is that Freed's Art Herstory is important in its original use of a new medium to question the historicisation process in both a critical and self-reflexive way. Like no one before her, Freed uses the unique characteristics of the video medium to formulate, and to perform, a multi-faceted critique of established art history.

Montage as critical tool

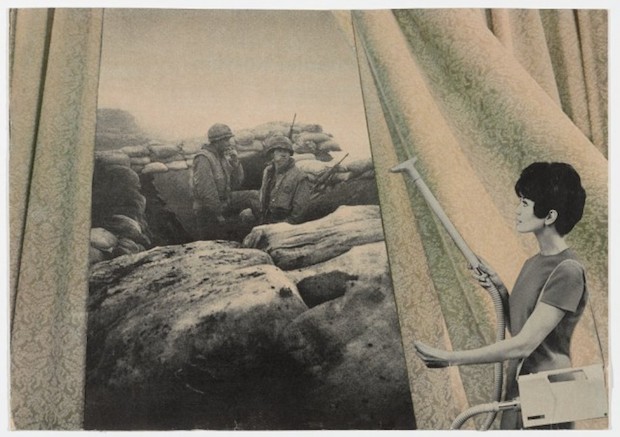

[6] In the following we will take a closer look at Art Herstory and the way it combines three types of material: the "disrupted" masterpieces, the dialogue, and the voice-over.

[7] The visual component consists of a succession of tableaux vivants, built around some twenty-odd pictures from the established history of art. We recognize paintings by a range of (male) artists: Raphael, Renoir, Cézanne, Picasso, de Kooning, Warhol, etc. The montage technique consists in disrupting these integral works. For example, the artist situates herself in medieval representation of the Madonna. The new dimension that is added to these static images is a consequence of the video medium; the familiar historical works are rendered mobile and thereby acquire a temporal aspect. In addition, the scenes are supplied with a soundtrack. Freed speaks sometimes to herself, sometimes to other performers, and sometimes to imaginary listeners. She talks quite a lot about how the work came about. The tone is informal, at times pensive, at others humorous. On a few occasions several speakers are talking simultaneously, making it difficult to grasp what they say. The work's third component, the voice-over, is supplied by Freed herself. She speaks in a calm and reflective manner that differs from the various dialogues, offering both a running commentary on the ongoing operations and general reflexions on her own work and its relation to history.

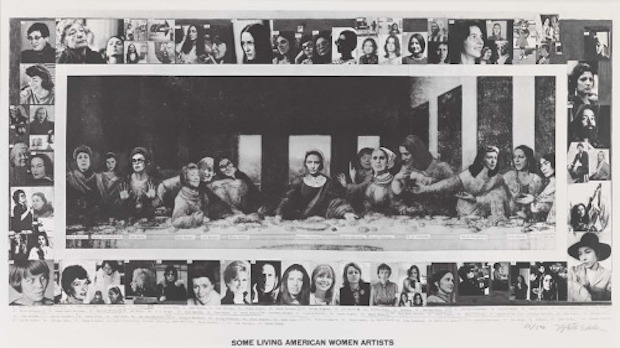

Hermine Freed, Art Herstory (1974).

[8] The title Art Herstory refers to both a feminist and a historiographic agenda. The American poet Robin Morgan is credited with having introduced the term herstory in her anthology Sisterhood is Powerful from 1970. "Herstory" is a central concept in the feminist critique of established historiography.

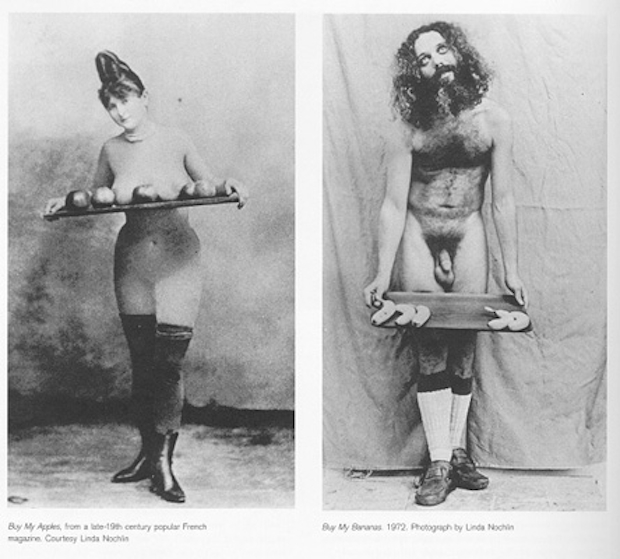

[9] In Art Herstory Freed uses the video medium to encourage a two-sided critique of art history's gender bias: how male artists have traditionally portrayed women over the centuries, and how women artists have traditionally been marginalized in the history of art. Freed "cuts and pastes," using art history as her archive. She is creating dialectical montages by means of intervention and by situating extraneous elements within canonical material. Besides Freed, several other (female) artists made pioneering use of pre-existent picture material in the 60s and 70s, including Martha Rosler, Dara Birnbaum, Mary Beth Edelson, Anita Steckel, and not to forget the Swedish film maker Gunvor Nelson (1931-). This so-called "found footage" could be taken from newspapers, magazines, radio and TV—i.e. from the public sphere—or from private photograph albums and documents. Freed's Art Herstory is, as I see it, indebted to a historically critical practice of the 1970s that has now been somewhat marginalised. My impression is that works from this period, especially the feminist works mentioned, bear witness to a growing awareness of the way formal and informal archives influence the ongoing process of historicisation in society. The critique is not infrequently articulated by placing found footage from established archives in new contexts, as the following examples will illustrate.

Martha Rosler. Cleaning the Drapes, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. 1967–72.

[10] Freed created all her video works in the 1970s, and like Art Herstory, many of them use found footage to highlight potentially controversial aspects of various historicisation processes. Family Album (1975), which is based on pictures from Freed's own childhood, demonstrates that the relevant events can be historicised in a variety of ways. Clips from TV broadcasts provide the archive material for the video New Reel, which Freed made in 1977. Juxtaposing clips of famous figures from the media—everyone from Richard Nixon to Mickey Mouse—and with the support of a voice-over, she investigates the foundations of social memory and the writing of our collective history.

Art History as archive

[11] Among other artists who also based their work on art historical material, Mary Beth Edelson seems particularly relevant in this context. In her collage Some Living American Women/Artists. Last Supper (1972), Edelson intervenes in the canonical painting by Leonardo da Vinci that she alludes to in her title. By replacing the disciples with a number of female artists, she not only documents their existence for posterity, but also writes them into history. Today, this work functions as an archive of the female artists who were significant to Edelson at that time. Ulrike Rosenbach is another artist who has made use of art historical material, notably in video works such as Don't believe I am an Amazon (1975) and Reflections on the Birth of Venus (1976/1978). Like Freed, Rosenbach interpolates herself into famous works, such as Gothic depictions of the Madonna or early renaissance works, such as Botticelli's Venus de Milo. Here again the feminist perspective is prominent. In the first of the above-mentioned works, Rosenbach shows an Amazon shooting arrows at a Madonna-like figure, thus juxtaposing two diametrically opposed archetypes from art history's range of women figures. In the second video, she problematises historical representations of the female body by placing pictures of her own body alongside the Venus de Milo. A parallel to this focus on conventional forms of presentation can be seen in Dara Birnbaum's Kiss The Girls: Make Them Cry (1979), which is based on the found footage of a TV entertainment programme. Although Birnbaum does not intervene in the actual images, she does mangle the rhythms and sounds of the original material. The cutting is repetitive and rhythmic, while all speech has been removed. A new soundtrack, a disco version of the nursery rhyme lines, "Georgy Porgie Pudding and pie / kissed the girls and made them cry," is superimposed on the images of male and female game-show competitors. The new rhythm and sound help to expose the dramaturgy of the entertainment programme, offering a startling account of the conventions of male versus female body language.

Mary Beth Edelson, Collage, Some Living American Women Artists. Last Supper (1972).

[12] Most of the artworks that feature in Art Herstory are depictions of women. They illustrate typical genres of female representation from art history, such as the Madonna figure, the refined upper-class lady set against a picturesque landscape, the scantily clad odalisque, the naked woman at her toilet, the painter's wife, etc. Freed disrupts these presentations by putting herself in the place of the represented women and commenting on her role, thus making us more aware, as did Rosenbach's works, of the roles traditionally ascribed to women in historical art.

[13] In taking the place of the various women figures, Freed uses an approach similar to that of Linda Nochlin in the latter's famous Buy My Bananas (1972), the masculine counterpart to the 19th century photograph Buy My Apples. The original photograph shows a naked woman offering apples to the viewer, a scene that is far too generic to be famous in itself. The masculine version, on the other hand, which shows a naked man presenting a plate of bananas, seems amusing. By repeating poses of a Madonna with child or an odalisque on a couch, Freed is using humour to make us aware of the representional conventions used in art.

Linda Nochlin, Photo, Buy My Bananas (1972).

[14] In addition to creating a dialectical montage, Freed turns the established chronology of art history on its head. She comments on this, by means of the voice-over in the video's introduction. The voice-over says:

The sequence of images on this tape is different from the sequence in which they were produced. Have I altered my history for the sake of world history? The depicted images did not necessarily happen in the same order in which the paintings were originally created. Did the artists alter history to fit their own ideologies? Have we, or they, reinterpreted the past in order to have it fit our own, or their own, model of the present? This has surely happened in the past.

In doing this, Freed's aim is not to propose an alternative history, but rather to use pictures as a means to focus our attention on issues relating to the processes of historicisation.

Secrets are disclosed

[15] One characteristic of Art Herstory is its striving for narrative transparency. Freed tells us repeatedly how the work is made, what choices it involved, and about various operations that are happening off-camera. This can also be seen as a reflection on the impossibility of such a transparency.

[16] These "secrets" are disclosed by means of the voice-over. The voice-over is a tool of somewhat dubious repute. It has been called "the voice of God" and is often criticized as manipulative, didactic and authoritarian. The traditional critique of the voice-over regarded the picture material as objective and untainted, but the voice-over as something that seeks, as it were, to enthrall and deceive the viewer. But, as film theorist Stella Bruzzi points out in her book New Documentary, this amounts to an oversimplification: "This gross over-simplification covers a multitude of differences, from the most common use of commentary as an economic device able to efficiently relay information that might otherwise not be available or might take too long to tell in images, to its deployment as an ironic and polemical tool." Since video artists in the 1970s usually had to handle all aspects of their productions themselves, they tended to use their own voices, one consequence of which is a wide variety of accents. In an interview I did a few years ago with Martha Rosler, we discussed various voice-overs in her video works, and touched upon this "voice of God" repute, she remarked: "I must begin by referring to one of my earliest critics, who noted that my voice-over had the unmistakable echoes of a harsh, Brooklyn working-class dialect." Her further comment is interesting in particular: "Because it was also a female 'take-no-prisoners' voice, I avoided the 'voice of God' paternalism, which the standard voice-over usually draws on. The voice simply wasn't suited to that, the critic reckoned."

[17] Among videos produced by artists during the 1970s and 1980s a variety of uses of voice-over is evident. Moreover, we see a new interest in using the voice-over technique for its critical potential in 1970s feminist works, with Freed as the earliest example, and some years later, Rosler. In videos like Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained (1977) or Domination and the Everyday (1978) Rosler uses several competing voice-overs at the same time. Yet Freed is using the voice-over in a totally new and self-reflexive, not to say self-critical, way. In Art Herstory, it is the voice-over that is most explicit in its critique of history, and it stands in a contrapuntal relationship to the rest of the work. Whereas the visual material and the on-camera dialogue have a hint of slapstick, the voice-over remains formal in its intonation. Freed adopts an intellectual habitus. She does not hide the fact that she is reading from a script, and with its rhythmic repetitions the text is both poetic and theatrical. At the same time, the voice-over has its own internal dialectic: on the one hand, it consists of a reading from an authoritative source, while on the other, it is interrupted at several points by the protagonists in the various scenes. Moreover, the voice-over undermines its own authority by revealing its own intentions and questioning the narrative that it is helping to construct.

[18] For example, during a scene in which we see Freed sitting in a Matisse interior, the voice-over confides in us as follows:

Hermine Freed, Art Herstory (1974).

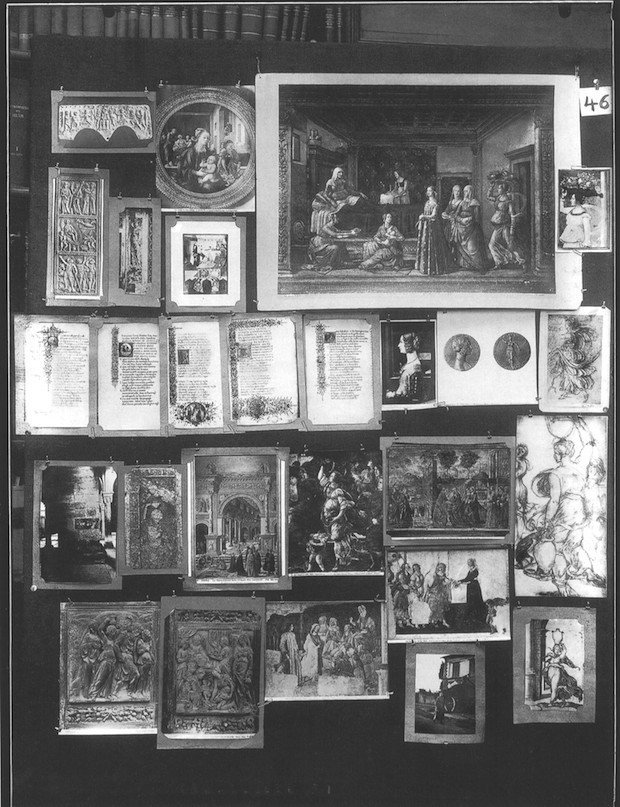

"I had planned and rejected an entirely different soundtrack in which I would have woven historical events throughout the images in this tape."

However, Freed's voice-over is not simply a means of disclosing the artist's intentions. It is also used to question whether such a intentional transparency is possible as in the following example:

... And how could you know, unless I tell you, which I may, that this was in actuality the first image that we recorded, merely as a test without a soundtrack. You might know, because there is or was no soundtrack... And how would you know, unless I told you, and I may, or may have already told you, that until today or yesterday an entirely different soundtrack was planned, which was different in turn from the original intentions of the tape.

Freed goes on to comment on the evanescent nature of her own intentions: "And what was the original intention of the tape? Much time has gone by since the first day. The intentions are constantly being altered."

[19] Further, the voice-over draws attention to aspects of chance in the creation of the work: "And if these were not my intentions, whose might they have been? I have thought of taking an entirely different point of view, which could have been equally true, equally valid."

[20] In other words, Freed's narration points out a number of unstable variables and is critical about how the artist herself is constructing a story by means of images and sounds. In addition, with reference to the feminist mantra, "the personal is political," she pragmatically emphasizes how an unfolding storyline is influenced by everyday events and activities:

Hermine Freed, Art Herstory (1974).

"Might I have altered centuries to squeeze in an image which was a substitute for the one I had really wanted, but which I could not, because of the events of the day, create? Would it have mattered what that image was?"

In addition to directing the viewer's attention to the underlying assumptions and mechanisms of historicising processes, Freed also comments on how versions of history become authoritative. Regardless of how much truth it contains, it tends to be confirmed again and again by different sections of the social machinery:

"... If events take place, if ideologies are created, if lives are lived, if wars are fought, if buildings are built, if institutions are founded on alterations of history, do those alterations not become more important, more real, as it were, than the actuality itself ..."

Freed is interrupting her own story telling again and again, and thus creates a Brechtian distanciation or defamiliarization where the viewer is liberated from the state of being captured by illusions of art. Illusion encourages passive identification with fictional worlds, and, as Pollock argues in Vision and Difference, this Brechtian distanciation was a central feminist strategy. The aim was an erosion of the dominant structures of cultural consumption, making the spectator an active participant in the production of meaning and activating him or her as an agent in the world. Freed shares this interest, and with her transparent story telling there is minimal chance for the spectator to be captured by illusions.

A good deal of humour...

[21] Concurrent with the voice-over asking these questions about historiography, numerous actions and conversations worthy of note are taking place. Freed does not conceal the fact that she and the other performers are using guile and ingenuity to create their scenes about art history. Not infrequently, the performers struggle to find their places within the pictures. The work process we are witnessing is laborious.

[22] During a scene in which Freed herself takes on the role of the Madonna in a 13th century Byzantine motif, she stretches out her arms towards the other performers, who appear as miniatures set in small medallions above her head: "I can't see you... I can't even see the monitor. [...] Give me a hand, Brucey [...]"

[23] When four different versions of her face appear in an imitation of a canonical Warhol grid portrait, one of the faces exclaims: "It is very confusing to see where I am. [...] I see myself the least in real time...[...] Sometimes I am confused which one is happening now..."

[24] The tone is casual, with many voices contributing to a volatile cacophony:

I like the first image... In the second one I look like Ingmar Bergman which is not a bad thing to look like, I mean Ingrid Bergman [...] In the first one [...] It does not look like me. In a way I like the imitation better than I do the real life replay [...] I don't think it takes the image as far as [...] I think it works better as an image than an imitation.

In other words, the ideal of transparency that the voice-over strives for, or reflects upon, is underlined both visually and by the performers' dialogue.

[25] Although it seeks to raise serious issues for debate, Art Herstory is bristling with humorous moments, satire, and slapstick. To my mind, humour is an essential but under-appreciated tactic of 1970s feminism. On a personal note, Nina Sobell's video Chicken on Foot (1974) was an eye-opener in this respect. During an interview with the artist at her home in New York, in which we discussed the historicisation of 1970s video, I presented Sobell with some questions about the video: What on earth does someone kicking the wall with a chicken on her foot symbolise? Obstacles? Confinement? I tried to formulate some (deeply serious) interpretations, which Sobell responded to with a chuckle, "There was a good deal of humour here ..." Ah! Humour was an element I had completely overlooked. Works and actions by the collective Guerilla Girls innate an element of humour, for example the poster with the unforgettable title, "Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?" Humour can also be found in works like Rosler's critical video about class and surrogacy Born to be Sold: Martha Rosler Reads the Strange Case of Baby M (1998).

[26] When Freed dresses up as the figures of canonical artworks, her appearances often have a touch of comedy, while the challenges of technology tend to be treated as amusing. In a scene where the performers are trying to find their places in a Raphael painting, with Freed seated on a throne as the Madonna, the small talk runs as follows:

Freed: "Where is Bruce? [...]"

Man's voice: "He is right under your nose."

Freed: "Here? No... I am looking at camera one now [...]."

Bruce: "I am getting a cramp."

Freed: "And what happened to the little boy? (Referring to Bruce)"

Man's voice: "Bruce has a cramp."

Freed: "Bruce has a cramp? How are you, honey?"

Bruce: "I am in agony [...]."

Man's voice: "Is it a religious agony?"

Bruce: "I will just look at you in adoration. [...] The show must go on [...]."

So, who's holding the camera now?

[27] Not infrequently, Freed makes remarks about the pictures she intervenes in. Roughly halfway through the video she finds herself in a painting by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath (1863). Like the female figure she embodies, she sits naked with her back to the viewer. But in her hand she is holding a camera, as she does in many other scenes in Art Herstory. Addressing the other participants in the painting, she says, "... Hold those poses. Very nice, girls. Keep it up for another minute or two. That will be really good. Thank you very much. Would you hold the camera please, honey? And that was a really [...] very nice performance."

[28] Other artists subsequently developed a similar kind of satire in their own montage works. One example is Joan Does Dynasty (1986), by the American Joan Braderman. Like Freed, Braderman situates herself within a pre-existing material, in this case, the soap opera Dynasty, which she tears apart with her ongoing commentary. Braderman lampoons conventional portrayals of the relationships between men and women, exhorting us even more explicitly than Freed does to view the original material with a critical eye.

[29] In Art Herstory, Freed appears in a variety of guises, generally assuming the roles of the female protagonists in famous paintings. She is often shown holding a camera, as in the Ingres painting and in the opening scene, as if to underline that she (or the female figure she represents) is now the one with the power of definition, the active narrator.

[30] During the 1970s, the cohort of people working with video in New York grew significantly. One reason for this is that the technology was becoming cheaper and easier to use, but the medium's rise in popularity can also be seen against the background of a growing dissatisfaction with mass media representations of life and a desire to establish alternative paradigms. Increasing resistance to the fetishisation of the art object spawned a desire to work with "immaterial" media. Video was regarded as a revolutionary medium with the potential to democratise the writing of history. It stood in opposition to television; now everyone could record the news, distribute information, write history. The video medium's potential for activism was at stake. Video was that time's tool of democratization, much as internet often is perceived today: a vast database—or archive—largely accessible for all kind of people across the world, offering new possibilities when it comes to sharing information and writings of alternative art histories. On the web today you can find a vast collection of marginalized art works inaccessible only a few years ago. UbuWeb is one such treasury, and not to forget digitalized magazines, like Radical Software and Heresies from the 1970s and 1980s.

Other archives

[31] Freed combines a feminist critique of historicisation with dialectical montage. Art Herstory represents an alternative to more linear and better established modes of presentation. It is not difficult to find examples of montage being used to describe an alternative history. Early montage films from the 1920s by filmmakers such as Esfir Shub and Sergei Eisenstein tend to be overtly political, if not indeed propagandistic. Not infrequently they were both commissioned and funded by the Soviet state. Other artists worthy of mention include John Heartfield and Hannah Höch, who both made collages, who aimed their critiques at, respectively, Nazi Germany and the Weimar Republic. The most notable historical precursor to Freed in my opinion is the German art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929). Like Freed, Warburg used montage as a method when working on his picture atlas, Mnemosyne, from 1927 until his death in 1929. For this unfinished atlas Warburg used material from various cultural fields to compile a kind of fragmentary and alternative history of art. Some thousand black-and-white photographs are distributed across sixty-three large wooden panels covered with black cloth. Images include classical and Renaissance art objects, as well as astrological images, maps, manuscript pages, and contemporary images from newspapers. The collages indicate various dialogues and relationships. Like Freed, Warburg was preoccupied with the fact that pictures form the basis of our social memory. He distances himself from a formulaic or stylistically narrow reading and suggests a rich context around the pictures.

Aby Warburg, Montage, page from Picture Atlas: Mnemosyne

[32] Both Warburg and Freed make use of familiar visual material stretching back many centuries. They use art history as an archive and rearrange well known images in order to make an alternative to established art history writing, and to reveal new and less visible aspects of the art works' form and content. In their different ways, each uses montage to highlight issues relating to historicisation.

[33] Other works that put archive material at play, and thus are part of Art Herstory's context, include Jean-Luc Godard's montage film, Histoire(s) de Cinema (1988-1998). Like Freed, Godard composes a self-reflexive (film) history, a personal archive, by means of montage. Therese Hak Kyung Cha makes a personal archive when she uses montage to portrait different women, her mother among others, in her poetic book Dictee (1982). Interesting contemporary artists worth mentioning in this context are Ursula Biemann and Angela Militopoulos, both of whom use archival materials in their video essays to address questions about gender, migration, labour or ecology.

[34] Feminist and queer projects that problematize the historicisation process by putting the archive at play are also relevant to mention as part of Art Herstory's context. In documentation projects such as re.act.feminism – a performing archive (2008-)—which deals with performance art of the 60s and 70s—we find a similar concern for what is marginalized. Consisting of live performances and a video archive among other things, the curators Bettina Knaup and Beatrice E. Stammer did a pioneer work in mapping feminist performance in East and West Europe. Another contemporary archival project that can be seen in relation to Art Herstory's revisionist spirit is the anthology and the three-part exhibition "Cruising the Archive: Queer Art and Culture in Los Angeles, 1945–1980" (2011–2012), an exhibition which explores the history of queer art, activism, and culture in Los Angeles through artworks, documents, and archival items culled from the collections at ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives.

[35] Queer theory, contemporary art, and historicisation are core themes in the Norwegian art historian Matias Danbolt's PhD, "Touching History: Art, Performance, and Politics in Queer Times" (2013). His study centers "on aesthetic practitioners with queer, feminist, and antiracist perspectives that negotiate between desire for alternative histories, and concern for untimely historicisations that risk disarticulating still pressing problems from the framework of the 'now.'"

[36] Art projects debating the archive's way of operating have been growing in number the last 20 years. One archive of specific interest in this context is The Atlas Group Archive (1989-2004) established by the artist Walid Raad. In this archive he collects various types of files documenting different parts of the Lebanon history. These files (videos, collages, photographies, texts etc.) are often both enigmatic, humorous and intentionally confusing. Raad problematises the archive's archaeological logic, and, as Freed did before him, he raises questions about how a specific history is written.

Critique through self-critique

[37] Traditional art history organizes objects and events into smooth narratives. Art historian Lisa Tickner gives a good description of this process in her 1988 essay, "Modernist Art History: The Challenge of Feminism." "Conflict, discontinuity, and overdetermination are smoothed into the comforting narratives of harmonious evolution, of the emergence of new styles from outworn convention." Tickner calls for a writing of history which replaces the notion of an omniscient, disinterested "histoire" with the more dialectical reality of writing as a site of conflict, including the conflict of different histories vying for hegemonic status. Feminist art history, states Tickner, has the potential to "question the adequacy and tidiness of particular forms, opening them to the struggle and chaos they work to suppress, it can write narratives of its own." There is a parallel here to what Freed is doing in Art Herstory. Her video is not concealing the chaos, conflicts, and coincidences of everyday life that usually are subjugated in traditional history writing. Instead, Freed's history writing in Art Herstory is transparent, equivocal, and full of conflicts.

[38] In Art Herstory Freed's voice-over questions the absolute certainty of written history, and comments on these smooth narratives of history: "History books represent the past with such a stunning clarity. Why does the present, which I can touch, taste, smell and experience, seem so out of focus, compared with the past?"

[39] Whereupon the voice-over asks rhetorically: "Can we say that history is more real than the present?"

[40] In Art Herstory Freed aligns herself with the feminist agenda while at the same time using the video medium's potential for montage to demonstrate a new approach to historicisation. As a distinctly self-reflexive and, not least, self-critical work, Art Herstory urges us to adopt a critical stance towards historicisation in general. By using her own body, and her own voice, she illuminates the collective processes of historicisation as subjective. When focusing on her own doubts and the chance of everyday life, she manages to comment on the contingent nature of history—"it all could have been different." Freed and her contemporary feminists have a common aim in criticizing the established art history tradition, but in Art Herstory a highly original strategy is used: Freed is presenting history as a messy process rather than a tidy tale. And moreover, her critique is indirect; it is channeled through the practice of self-critique. By highlighting strata of her own narrative that would otherwise pass unnoticed, she indirectly draws attention to hidden aspects of other forms of narration. If this video work entails so many less-than-obvious operations and reflects more or less arbitrary inclusions and omissions, then what lies concealed beneath more complex accounts of events, such as television news broadcasts, documentaries, and history books? How do these narratives get written, by whom, and for whom? Freed's work prompts us to think that the established narratives are built on a series of hidden operations that are guided by more or less conscious choices, compromises, and conventions.

Notes

- The work was made while Freed was an artist in residence at the Television Lab at WNET. From 1972 Freed taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York. She died in 1998.

- I saw Freed's Art Herstory for the first time at the New Museum in New York in 2008, during a seminar on video art organised by the American artist Martha Rosler, who was herself an active video artist in the 1970s. Among other things, the seminar focused on the social context in which early video art was produced. Rosler showed works from her private video collection, a significant number of videos which date back to those early years. I was motivated to attend Rosler's seminar by a number of concerns: how the early history of video art was recorded, the apparent erosion of nuance in the history of the medium, the widespread tendency to ignore its socio-political aspect, and the marginalisation of female practitioners. Many of the works Rosler showed are now virtually unknown.

- As in Beryl Korot and Ira Schneider (eds.), Video Art: An Anthology (New York: Harcourt Brace Jonanovich, 1976).

- Curated by David Ross. For a review, see David Ross, "Circuit: a video invitational at the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York," Radical Software 2, no. 5 (1973): 32-35.

- See the list of these feminist exhibitions in the magazine n.paradoxa: «http://www.ktpress.co.uk/feminist-art-exhibitions.asp». She is, however, mentioned in Sigrid Adorf's book Operation Video. Eine Technik des Nahsehens und ihr spezifisches Subjekt: die Videokünstlerin der 70er Jahre, (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2008). Her work has in the later years been exhibited rarely and shown only at a few occasions. Art Herstory was screened at The Wexner Center of the Arts, The Ohio State University, in 2006. The video was also screened in the exhibition "Documenting a Feminist Past. Art World Critique" at The Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Education and Research Building, MOMA, in 2007. And further in a seminar/workshop about historicisation and montage, organized by editor/writer Halvor Haugen and art historian Nina Schjønsby at Oslo National Academy of the Arts, Oslo, Norway, in 2012 ("Tvers over bånd og grenser: klipp og lim"/"Across bounds and limits: cut and paste"). Freed was also represented on "The Moving Image Video Fair" in New York in 2013, with her video Two Faces (1972).

- Moira Roth, "Teaching Modern Art History from a Feminist Perspective: Challenging Conventions, my Own and Others," in Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology 1968-2000, ed. Hilary Robinson (Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2001), 142.

- Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and the Histories of Art," (1988; reprint, London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 7.

- Ibid., 16.

- Ibid., 13.

- Ibid., 9-10.

- Morgan co-founded both the feminist organisation W.I.T.C.H. and the collective New York Radical Women. In Sisterhood is Powerful she writes: "The fluidity and wit of the witches is evident in the ever-changing acronym: the basic, original title was Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell [...] and the latest heard at this writing is Women Inspired To Commit Herstory." See Robin Morgan, Sisterhood is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement, (New York: Vintage, 1970), 65.

- A dialectical montage, as Rancière writes, consists of heterogeneous elements juxtaposed so as to clash (a technique that can be compared with what Sergei Eisenstein calls conflict in Film Form, 1949). Rancière contrasts this with symbolist montage, which tends to exploit subtle relationships between the various elements. See Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image, (2007; reprint, London and New York: Verso, 2009), 56-67. See also, Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form: Essays in Film Theory and the Film Sense, (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1949).

- Nelson's brilliant feminist film Schmeerguntz was made as early as 1965, of visual and audio found footage. Anita Steckel made use of found photographes in her montage series called Mom Art, in 1963 (she was active until her death in 2012, making political collages, for example The Bush series).

- Freed also made many video documentaries about women artists in the 1970s. Several of these are now in the archives of the Video Data Bank in Chicago.

- Freed uses both private photographs and film footage from her own childhood and adolescence in a montage that explores the changeable nature of memory. She sets her own memories alongside those of others, showing how they differ. Here again, the focus is primarily on historicisation rather than Freed's own biography.

- Edelson does the same with Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

- The German titles of these works are Glauben Sie nicht, dass ich eine Amazone bin and Reflexionen über die Geburt der Venus. Although German by birth, Rosenbach became part of the New York scene in the 1970s. She featured in the above-mentioned exhibition "WACK!"

- This view of the voice-over is held by the filmmakers and theorists Robert Drew and Bill Nichols. See Stella Bruzzi, New Documentary: A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2006), 47-73.

- Ibid., 50. Bruzzi also stresses that such voice-over was used in documentaries even before the 1960s, by practitioners such as Buñuel, Huston and Franju. Direct cinema-pioneer Robert Drew criticized voice-over in articles such as "Narration can be a Killer" (1983).

- Interview by Nina Schjønsby, Billedkunst, Feburary (2006), Oslo.

- In works by Vito Acconci, Harun Farocki, Chris Marker, and Nancy Holt, just to mention a few.

- Martha Rosler has also explored the use of voice over in later videos like A Simle Case for Torture, or How to Sleep at Night (1983) and If it is too Bad to Be True, It Could Be Disinformation (1985). This experimental use of the voice-over is taken further by contemporary video artists, like Ursula Biemann and Angela Militopoulos.

- Pollock, 223-224.

- Original title: Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne. In the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

- One can ask whether the element of slapstick in Art Herstory influenced the work's reception. It is worth mentioning that an exhibition titled "Backflip: Feminism and Humour in Contemporary Art," curated by Laura Castagnini, opened in 2013 at the VCA's Margaret Lawrence Gallery, took a look at the funny side of feminism.

- Additionally, Situationist artist Guy Debord appropriated commercials and advertisements in his political critique La Societé du Spectacle (film, 1967).

- Originally, he intended to use text as one element in this atlas. For further reading: Christopher D. Johnson, Memory, Metaphor and Aby Warburg's Atlas of Images, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2012).

- Warburg is maybe most known for introducing the method of iconography and iconology into the art history discipline (developed by art historian Erwin Panofsky).

- Warburg focused on the picture's political, anthropological, sociological and psychological functions. This was a new way of thinking about the history of art. For Warburg, however, montage served as a heuristic tool rather than a means of producing finished work.

- Like in Biemann's Performing the Border (1999), X-Mission (2008), or Deep Whether (2013), and Angela Militopoulos' Timecapes/B-Zone (2005-2006), or her project with Maurizio Lazzarato on Félix Guattari, entitled Assemblages(2010-).

- Organized at Akademie der Künste in Berlin (2008–2009). Followed by re.act.feminism vol. 2, a performing archive (2011-2013).

- The largest LGBTQ archive in the United States.

- Cited from Danbolt's own homepage, «http://mathiasdanbolt.com/». His interest for alternative knowledges is inspired by Judith Halberstam. Her books Female Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1998) and In a Queer Time and Place (New York: NYU Press, 2005) have become central references in academic, cultural, and activist discussions in the U.S. as well as in Nordic countries.

- See Lisa Tickner, "Modernist Art History: The Challenge of Feminism," in Robinson, Feminist-Art-Theory, 250-257.

- Ibid., 252.

- Ibid., 255.