Steampunk Anachronisms:

Queer Histories of the Digital Humanities

Roger Whitson

Washington State University

[1] On March 17, 2012 Miriam Roček was arrested along with over seven hundred Occupy Wall Street protesters in a failed attempt to retake Zuccotti Park. Roček, dressed in her "Steampunk Emma Goldman" persona, had been arrested with the protestors three times before and participated in numerous events with the Occupy movement including a reading of Goldman's 1909 speech "A New Declaration of Independence," the previous fall. "Right after the Brooklyn Bridge arrests" Roček explains in an interview with The Local East Village, "[...] The New York Times printed this article where they said that if the NYPD tried to clear Zuccotti Park, it would result in the resurrection of Emma Goldman. And I thought that was a great idea!" Roček had played the part of Goldman before, but not as part of a political movement. The editors of Steampunk Magazine called Steampunk Emma Goldman "cosplay done right." Cosplay, of course, abounds as a form of cultural expression where fans dress up in costumes of their favorite characters at comic and fantasy conventions throughout the world. Yet, Roček's persona is unique in her ability to participate in historical, fantasy, cultural, and political environments simultaneously. Cultural expression and representation, for Roček and for Steampunk Emma Goldman, becomes a form of participation in a contemporary historical event.

[2] Steampunk Emma Goldman is a powerful example of how steampunk is able to appropriate historical images and events as tools to help people participate politically. Steampunk has been described as "Victorian Science Fiction," but it has become far more than simply a subgenre of science fiction. As a backdrop for novels like Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials and Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age, films like Wild, Wild West and television shows like Firefly, steampunk satisfies the desire of some fans to explore different alternative histories of science fiction and technology. In fan communities devoted to the genre, steampunk engages identities and concepts that help fans of the nineteenth century remix its gadgetry, fashion, and writing. History and culture in steampunk are both seen to be freely available for tinkering and recreating. In the introduction to What is Media Archaeology, Jussi Parikka notes steampunk's rejection of linear understandings of history in favor of a do-it-yourself (DIY) attitude towards "alternatives," "quirky ideas," and "novel paths that fall outside the mainstream" (2).

[3] The anachronisms Parikka identifies with steampunk can offer insights into the complexities of developing identity and community within the digital humanities. Despite William Pannapacker's oft-cited invocation of "big-tent digital humanities," many scholars reasonably or not continue to see DH work as primarily methodological and tool-oriented. The authors of Digital_Humanities, for instance, contend that DH doesn't include "[t]he mere use of digital tools for the purpose of humanistic research and communication" nor "the study of digital artifacts, new media, or contemporary culture in place of physical artifacts, old media, or historical culture" (122). Along with questions about the role of coding, building, and collaborative practice in defining the digital humanities, DH scholars struggle with the place of critique, cultural studies, and institutional history in their discipline. Adeline Koh has recently called for understanding alternative genealogies for the digital humanities beyond humanities computing, citing in particular the work of Lisa Nakamura and new media studies as welcoming "self-reflexive critical approaches that blend media theory, race, gender, and cultural studies, and political critique about technology and culture" (102). I suggest that steampunk can offer another alternative genealogy: one rooted in the history of the nineteenth century, but one that also seriously considers the role of technology on adapting and transforming our relationship with the past.

[4] Adaptations of the nineteenth century never occur without political consequences. In particular, steampunk has been criticized for being largely silent about the disparities of power occurring in the nineteenth century. A 2010 post by Charlie Stross, for instance, critiqued steampunk for its "romanticization of totalitarianism" in an era when "[l]ife was mostly unpleasant, brutish, and short; the legal status of women in the UK or US was lower than it is in Iran today: politics was by any modern standard horribly corrupt and dominated by authoritarian psychopaths and inbred hereditary aristocrats." Still, steampunk shifts the stakes of political representation. I connect the anachronistic fan performance found in steampunk with a struggle against what Elizabeth Freeman has identified as chrononormativity "or the use of time to organize individual human bodies toward maximum productivity." For Freeman, this has the consequence of making people "bound to one another, engrouped, made to feel coherently collective, through particular orchestrations of time" (3). For the digital humanities, time and collectivity tend to be orchestrated by the development of new technologies. Wordpress and Twitter make it easier for scholars to participate online and thus imagine their communities in those spaces. Gephi and Mallet enable the use of visualizations in research. Omeka streamlines the development of online digital archives. Humanities scholarship is reimagined along the codes and standards of specific groupings of technological development. As a self-consciously anachronistic discourse, then, steampunk contests the technological orchestrations of community and challenges the digital humanities to imagine alternative, perhaps queer, forms of association.

Queer Nineteenth Centuries

[5] I argue that the queer remaking of the nineteenth century by steampunk authors and fans can help us understand the complexities of thinking through these alternate histories of the digital humanities, along with their presentation on social media. I agree with Jaymee Goh, who identifies steampunk participation as a form of "self-fashioning" in which "each person decides to what degree they indulge in whichever element, pulling together different influences in order to create a composite whole." It is this aspect of self-fashioning that Goh suggests makes it so difficult to define steampunk as a whole. Yet self-fashioning is also a commonplace idea among nineteenth-century scholars who study queer identity during the period. Richard Dellamora's landmark 1999 collection, Victorian Sexual Dissidents, begins by remarking how "[m]ale poets and writers of nonfiction prose during the Victorian period use the discursive space afforded within a number of aesthetic genres to begin to imagine embodied, intimate, at time sexualized ties between men" (9). This spirit of experimentation is also articulated through different technologies, which acted in the Victorian period as channels for queer desire and anxiety. Kate Thomas shows, for instance, how the employment of telegraph boys as prostitutes in the 1870s and 1880s illustrated the dangerous potential for Victorians of the postal system as a circulating mechanism for sexual deviance. Likewise, Jay Clayton identifies the use of the telegraph in Thomas Hardy's novel A Laodicean with "a queer space" and contrasts that with the optical instruments used by the male character "whose aim is the possession of the heroine's body and castle" (73).

[6] Nineteenth-century scholarly accounts of sexuality are important because they parallel, yet are also complicated by, the issues surrounding queer steampunk identity and culture. Consider an account by Ashley Rogers, in which the heterosexualized opticality of photography is used in an attempt to capture transgender identity. Rogers performs as "Lucretia Dearfour," a transgender activist who also appears in comedy and performance troupes at conventions. While acknowledging the progressiveness of many members of the steampunk community, Rogers also mentions so-called "pitty [sic] pictures." "They'll wrangle all the cute girls in my group together and leave me out for a few shots," Rogers recalls, "then all of a sudden (as if thinking 'Oh crap I'm not a homophobe') they'll say 'You too,' or 'Get in there!' and take one picture." The same observational logic is behind what Rogers calls the desire of "cis folk[s]" to ask her about "my deepest and darkest secrets; particularly the state of my genitalia." The visibility of queer steampunk fans is often shaped by the heteronormative corset fantasies fans are assumed to hold. "I understand the notion that to Average Joe American a Steampunk is a fat white dude in a pith helmet with goggles who says 'Bully,'" Rogers continues "and a Steampunk woman is a buxom, corset clad, lady with tiny glasses to show class and tiny hiked up skirts to show ass. This does not mean I accept this notion of a Steampunk."

Ashley Rogers

[7] The tension between convention photographers and fan bloggers epitomizes a culture where the already complex issue of queer representation is made even more uncertain by competing technologies. In the late nineteenth century of Hardy's novel, photography captured sexuality by producing an image that could be displayed inside a home or published in a newspaper. Nancy Armstrong, for instance, has shown how photographers sought out "picturesque scenes and rustic people" for refuge from the increasing stresses of city life, and that "the countryside served as raw material for photographs that consumers could enjoy at exhibitions, in galleries, and even in the comfort of their own homes" (4). Photography delegated cultural difference as a commodity that urban observers could enjoy as a form of escapist entertainment, provided that such difference was not considered unacceptable for consumption. The history of Victorian pornographic photography is interesting in this regard, particularly as it related to the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which allowed for arrest and the destruction of materials that included nudity for sale in books and prints whether or not such materials were intended to corrupt. Lisa Siegel outlines how the act reinscribed many of the social hierarchies that would later dominate the consumption of pornography in the late nineteenth-century. As Siegel observes, many of the progressive, libertine pornographers early in the century were interested in using woodcuts, lithography, and other illustrations to give the illiterate working class access to pornography. Yet, despite the law's ruling that any and all pornography should be confiscated regardless of intention, Siegel argues that its unequal application made the consumption of pornography the privilege of upper-class men, while the disadvantages of colonial subjects, lower-class women, and other marginalized groups meant that they were restricted from viewing pornography or became themselves the object of the voyeuristic white-male gaze.

[8] This question of the voyeuristic gaze still remains a privilege of a specific group of white-male fans in steampunk, and yet however much convention photographers use their audiences to create commodified forms of visibility featuring traditionally heteronormative voyeuristic images of steampunk culture, queer and transgender steampunk performers have their own platform on social media sites. Steampunk follows what Henry Jenkins, Joshua Green and Sam Ford calls, "a more participatory model of culture, one which sees the public not as simply consumers of preconstructed messages but as people who are shaping, sharing, reframing, and remixing media content in ways which might not have been previously imagined" (2). Rogers took to the blog Beyond Victoriana, written and edited by Diana Pho, to contest the heteronormative media representation of steampunk. "I feel like the media has a certain view of what Steampunk is and aren't interested in questioning that," Rogers observes, "Anything deviating from that perfect Caucasian/Victorian Steampunk would confuse people, would horrify people, or would lose ratings." Despite reactions that so-called "average viewers" would think of steampunk "as a gay thing," Rogers stages her intervention by questioning how the idea of a normative steampunk presumes "straight white audiences." Rogers continues "[t]he 'steampunk community' has NEVER been exclusively straight or white. Steampunk is a construct of loose ideas tied together like a quilt, or a post-apocalyptic flag." Rogers's image of a post-apocalyptic flag is particularly provocative as it challenges the imperialist and nationalist ideas that critics like Stross take to be central to the experience of steampunk. As a normative discourse nostalgic for the Victorian past and disseminated by traditional media outlets, steampunk does indeed run the risk of celebrating racism, sexism, and colonialism. Yet by appealing to new audiences made possible by social media and participatory culture, Ashley Rogers is able to rip apart old flags and stitch together her own post-apocalyptic queer community with their remains. Rogers is quick to defend this community who she said, in an email conversation with me, has been extremely generous to her. When Ashley found herself faced with the difficult decision to stay in an unsupportive living situation or be homeless, steampunk fans offered her their own homes.

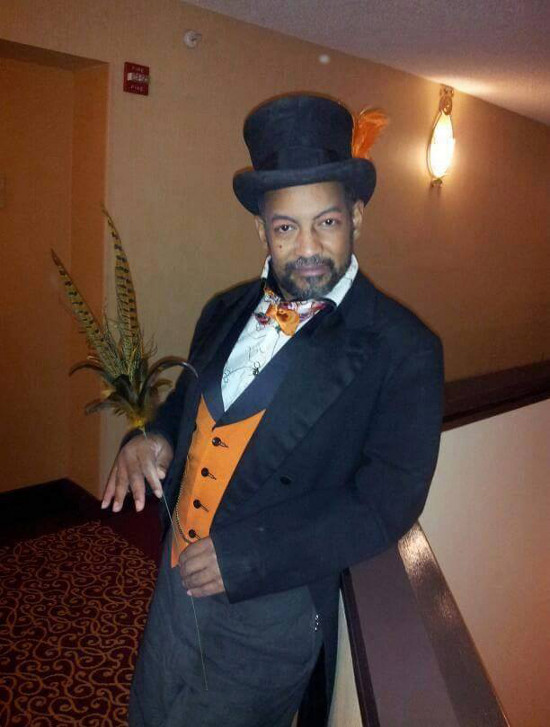

[9] The theme of a supportive, but also sometimes ignorant, steampunk community formed out of participatory culture is common with queer performers. Philip S. Powell, who dresses up and identifies as a dandy, similarly noticed in an email to me "no outright homophobia or racism," yet notes that sometimes people make mistakes because many of them "aren't exposed to the realities of [race and sexuality]. Otherwise there would be more dandies." It is important to underscore the fact that steampunk's participatory communities aren't perfect. Queer fans are still marginalized, sometimes in ways that are obscured by the presumption that the community has a welcoming atmosphere. In an interview with Jaymee Goh, Powell explains that his dress challenges the implicit "Great White Society" that held dandies as exemplars of masculine civilization during the Victorian period ("Steampunk POC"). He says he "turn[s] that [white masculinity] on its ear" by becoming a dandy and being "a gentleman of renowned elegance, style and fashion of the times, all the while myself being, well, non-white." Powell sees his dandy costume as an accessory, a gadget that performs his subversion of white Victorian history. "I wear very fancy outfits, feathers, accessories, pins, brooches, THOSE are my gadgets," says Powell. The connection between costume and mechanism is not uncommon in steampunk, yet Powell's analogy between gears and seemingly common clothing accessories questions the fandom's technofetishism. Powell is critical of steampunks who see the fandom as wrapped up in "How many gears? How many gadgets?" as he explains, there is "nothing wrong with either as long as you respect those (like me) that feel neither are required, just optional if you accessorize correctly.

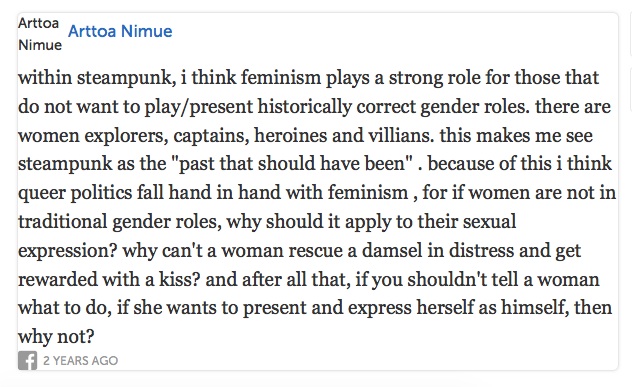

Philip S. Powell

[10] The blending of politics, technology, and fashion has been part of the dandy identity from the beginning. Rhonda Garelick has argued that the dandy in the nineteenth century existed between "early mass culture and the contemporaneous Decadent movement" (4) This means that "[a]lthough the typical dandy hero loved to go 'slumming' and visit actresses, 'ballet girls' and prostitutes, the later decadent dandy experienced such social encounters as they were altered by socially-leveled audiences, urban crowds, the rise of media spectacles, and the resulting mechanized representations of the female body" (112). The arrival of early mass culture meant that mechanized forms of reproduction transformed how decadent dandies approached their identity as images of dandies began appearing on films, in photographs, and on advertisements. For Garelick, status within the dandy community became increasingly defined by the acquisition of commodities and participation in the mass circulation of cultural artifacts. Even though scholars like Stefania Florini and Elaine Freedgood have argued that it is difficult for us to assess the meaning of objects and accessories in the nineteenth century due to our own historical immersion within late-capitalism, it is clear that class changes catalyzed by the technological shift to mass culture in the Victorian period changed what it meant to be a dandy.

[11] These transformations are also modified by the cultural meaning of the black dandy. Monica Miller has shown how black dandyism emerged as the use of trinkets or accessories by black slaves as subversive mementos to recall their former lives in Africa, resist the new identities fostered upon them by bondage, or to create new modes of distinction in a life that was defined by material deprivation. Miller continues that this process of modification and distinction "is as true for those who were deliberately dressed in silks and turbans, whose challenge was to inhabit the clothing in their own way, as for those who were more humbly attired" (4). The story of the dandy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries can thus be seen looping between fashion and technology. Even as the white dandy experienced shifts in audience and class distinction brought on by new modes of cultural expression and promotion, the black dandy experienced these shifts as opportunities to mod fashion technologically and produce new spaces for resistance by queering the relatively more normative performances of other dandies. As Miller points out, black dandies are "quare" rather than distinctly queer since they perform queerness "with a distinctly black accent" that is "at once a threat to supposed natural aristocracy, he is (hyper) masculine and feminine, aggressively heterosexual yet not quite a real man, a vision of an upstanding citizen and an outsider broadcasting his alien status by clothing his dark body in a good suit" (11).

[12] Social media transforms these meanings once again. Empowerment, promotion, queerness, race, and participation are tightly intertwined as the emphasis on sharing, modifying, and performing variations of Victorian identity require new approaches to old problems. Social media also gives more forums to participate in activism. In a post on Tor.com, Lisa Hager mentions the need for "gender neutral bathrooms [to] become a regular part of all steampunk conventions so that *trans people at these events can use con facilities without [being] questioned about their gender identities." For Hager, there is a need for more trans-performances, but convention spaces for those performances aren't always designed to welcome transpeople. Hager also organizes panels of academic and non-academic steampunk fans designed to address the more nuanced queer politics within the fandom such as "micro-aggressions and tokenism." In "A Queer Love Letter to TeslaCon III" that she shared with me, Hager mentioned that she is particularly interested in the way fans "so often articulated complex and contradictory connections between Victorian ideas of gender and sexuality, our own society's relationship to those ideas, and steampunk's revising of both." She sees that "it is essential that my discipline engage with steampunk and value its unique expertise in the period, while, at the same time, continually offering questions that encourage the community to continue its tradition of analysis":

A Queer Love Letter to TelsaCon III

In November of 2012, I had the pleasure of moderating a round table on gender and sexuality titled "More than a Little Bit Queer: Steampunk, Sexuality, and Gender Identity" at TeslaCon III, which included Karina Cooper, Lyndzi Miller, Kevin D. Steil, and Scott Velasquez. As an active member of the steampunk community and a scholar of Victorian studies, I had put the panel together largely through recommendations of friends and various social media groups. Much to my anxiety at the time, I had not met a single one of the panelists who had so graciously agreed to be a part this discussion, nor did I have any idea if anyone would attend such session in the midst of TeslaCon III's busy panel schedule.

But attend you did, my fellow steampunk queers and allies! We filled the room to capacity with people and ideas. In our time together, we discussed issues as basic as LGBTQIA visibility in steampunk literature and culture and as complex as micro-aggressions and tokenism. What stands out me about this conversation were the ways in which my fellow steampunks so often articulated complex and contradictory connections between Victorian ideas of gender and sexuality, our own society’s relationship to those ideas, and steampunk's revising of both.

For me, as a scholar of Victorian studies, this session made clear to me that it is essential that my discipline engage with steampunk and value its unique expertise in the period, while, at the same time, continually offering questions that encourage the community to continue its tradition of analysis. I hope to be able do so as this one roundtable becomes a series of panels and roundtables at this year's TeslaCon IV: Congress of Steam!

XOXO

Lisa Hager

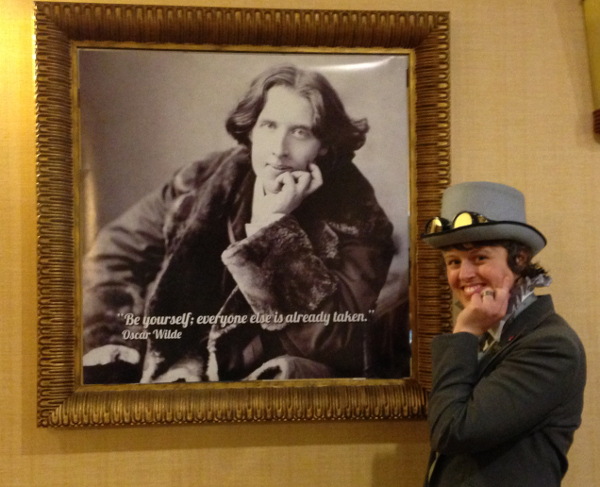

[13] Hager's vision of a conversation between the academic world of nineteenth-century scholarship and steampunk fandom illustrates just one of many potential alternatives to chrononormative academic understandings of nineteenth century history. As Hager uses her academic knowledge of Victorian sexuality to complicate the heteronormative versions of steampunk, she also suggests a gap between academic histories and the performance of the nineteenth century embodied by steampunk fans and activists. For me, her intervention parallels Eve Sedgewick's critique of a suspicious historicism understood as a "mandatory injunction rather than a possibility among other possibilities" (125). Instead of focusing on the truth-value of nineteenth-century accounts of history, Hager looks to steampunk as what Hancock et al. calls "possibility-spaces" for imagining new uses for historical knowledge. She extends her understanding as a form of queer community building, in which displacing the exclusive hold academia has on historical knowledge becomes an essential part of creating bonds with people outside of the University. For Hager, as for many people involved in steampunk, anachronism is a form of connecting.

Lisa Hager

Chrononormativity and Reparative Digital Humanities

[14] The queer nineteenth centuries presented by the steampunk fans I've presented are very different from the historical periodicity crafted by research. Anachronism creates multiple possibilities around the question of how diversity impacts the steampunk community — and constructs what Jose Estaban Muñoz would call a queer utopian impulse. "We have never been queer," Muñoz argues, "yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future" (1). I decided to collaborate with steampunk scholar and activist Diana Pho (@writersyndrome on Twitter) to see just how members of the fandom saw the importance of political struggle and queer representation. In a Twitter conversation, I expressed the concern that while many steampunk fans saw equality as important they also considered queer issues to be marginal.

[15] Diana's sketch of a form of openness in the steampunk community, combined with a rejection by some members of the label of "politics" for clearly political actions was reflected in answers to the question she posed to the community on my behalf. Pho used her Twitter account and her Beyond Victoriana Tumblr page to ask "[w]hat role do feminism and queer politics have in steampunk? What role should they have?" ("Politics"). She received a number of responses, particularly on her Tumblr page, but I only have room to publish some highlights. I also refrained from editing the responses due to grammatical errors or typos. For many of the fans, the issue lay in what possibilities are open for people to perform different social roles. Arottoa Nimue, for instance, argued that feminism was important for "those that do not want to play/present historically correct gender roles." She continues:

[16] Patricia Ash, editor of Gearhearts Steampunk Glamour Review, agreed. She said that in steampunk:

Clearly, both Ash and Nimue named political struggles without identifying them as political. While Nimue asserted the idea that people should be able present themselves with any gender ("why not?"), Ash suggested the performance was an essential part of steampunk fandom ("it's a playground with no bullies.").

[17] More pointed responses underlined the social importance of queer performance. holzmantweed.tumblr.com, for instance, argued that "our politics are inseparable from our survival." Survival, it seems, is more than a question of acceptance. It also lies in identification, in understanding who constitutes "us" or "we":

[18] brsis.tumblr.com chose to emphasize the possibility of "fixing" history with steampunk:

[19] kiskidee.tumblr.com agreed, insisting that steampunk must include queer elements:

[20] Many fans were adamant about having a community that reflected what they wanted to be, not just the discriminatory realities of the Victorian period. thejeniverse.tumblr.com mentioned the need of "visionaries like steampunks to build a better world" that addressed "feminist and queer issues." goodshipsappho.tumblr.com mentioned their Tumblr blog, which tells the story of a "smuggling collective" comprised of people who are excluded from the official economy "because all the characters are female, because they are queer, because they have disabilities, etc," asserting that "Steampunk wasn't just for cisgender straight white British people." Finally, alexanderdsoso.tumblr.com emphasized that "while the dress, technology, and mannerisms of steampunk can often be of the 1800s, the issues addressed need to look ever to the future, and who we are, and want to be, as humans."

[21] The responses to my question were inspiring, but also reflect the ease with which queer identities are incorporated into social formations of power online. Jacob Gaboury argues that digital technology has effaced traditional sites of queer struggle by incorporating the performance of identity into the metadata schemes and signal processing of social media. The new site of struggle, Gaboury argues, is in "forms of computation that fail, break down, recur, and run forever, and models of computing that are outside of or beyond so-called 'universal' Turing computation – that is, those processes which disappear or recede from computational forms of knowing." Alexander Galloway's book on the philosopher Francois Laurelle gestures against digitality in a similar manner by pointing out that digital images are no longer images but "aggregations of cells that combine and coordinate to create some whole." This model Galloway contends extends to digital culture, which has metastasized into a reverse panoptic community. "[A] multiplicity of watchers all collaborate to convene upon a singular point," Galloway argues, "[t]he poorly differentiated adenoid carcinoma point, while the 'subjective' points of view have metastasized into multiplicity." The ease of connectivity and the multiplication of tags that can be assigned to any user creates a model of subjectivity that is endlessly viewable and identifiable, constructed not so much out of performance but out of the many numerous clicks that tag photographs, blog posts, and profiles. Meanwhile, queer politics metastasizes into a giant tumor comprised of endless meta-tagged identities.

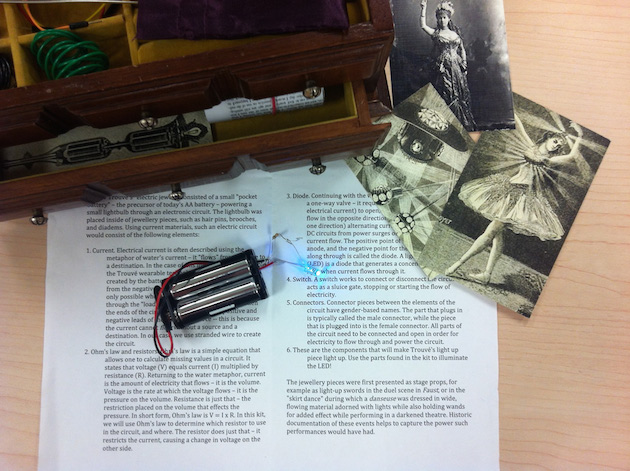

[22] To be sure, Gaboury and Galloway are more interested in the political and technological implications of the surveillance system encoded by digitality than the specific issue of queer representation. Gaboury, in particular, takes his cue from Lee Edelman's insistence of the queer as embracing the negativity associated with a refusal of participation — a sensibility that is very different from queer steampunk fans who want to participate or queer digital humanities scholars who desire inclusion into a "big tent" definition of the field. But I do think Gaboury's insistence upon technologies outside of the smooth connections and sleek interfaces often found in technological boosterist discourses can help us link steampunk to forms of queer digital humanities practice. For instance, the construction of alternate worlds in steampunk provides a parallel to what Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka have called "zombie media" where practitioners revive dead gadgets with the purpose of contesting the planned obsolescence of consumer technology cycles and assembling them "into new constructions, [where] such materials and ideas become zombies that carry with them histories but are also reminders of the non-human temporalities involved in technical media" (429). Hertz and Parikka see circuit-bending as one such example of zombie media practice: DIY artists like Rheed Ghazala open up Speak & Spell electronic devices, find "bends" or points where electronic current flows that were never intended by the manufacturer, and use them to create highly customized electronic music devices. Another example can be found in the University of Victoria MakerLab's "Kits for Cultural History" project, in which new technologies like laser cutters are used to create Victorian jewel caskets, a wearable technology featuring electronic jewelry designed by Gustave Trouve in the 1860s and 1880s. Despite the seeming anachronism, project contributor Nina Belojevic argues that the laser cutter had precedents in the manufacture of the nineteenth-century jewel boxes. "With the development of new manufacturing equipment and techniques," Belojevic explains, "small pieces could be produced faster and cheaper than before. [...] While our methods and tools are clearly different from the ones during the 19th century, our approach is similar in that we are also using technologies to allow for wider circulation, thereby making our pieces more readily available (or so we hope!) for production and use." These examples, gesture toward Muñoz's notion of a "queerness [which] is essentially about the rejection of the here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world" (1). The possibilities embedded in the alternate worlds of steampunk imagine how different kinds of cultural history could emerge from the violence of a past we already know.

Nina Belojevic's prototype for the Victorian Jewel box. Photo by Shaun MacPherson.

[23] Similarly, looking at the complex emerging multiculturalism of steampunk fandom, in which racist, sexist, and heterosexist forms of cultural appropriation coexist with more complex reimaginings of cultural forms in alternate histories, Diana Pho advocates "polycentric multiculturalism" as a critical apparatus. Quoting Ella Shohat and Robert Sham, Pho sees polycentric multiculturalism as emphasizing less the "artifacts, canons, and representations" of steampunk and more the "communities" behind steampunk, along with their conceptualization and "re-conceptualization of power relations between cultural commodities" (qtd on 21). She adds that steampunk forms of polycentric multiculturalism would focus on the "ethical implications" of steampunk conversations, the "contextualization" of steampunk art, and the "accountability that steampunks hold to each other in discussions about race, culture, and historic oppression" (22). Along with these conversations about oppression, I feel the utopian impulse behind imagining history differently presents a very different form of cultural critique in which new possibilities can be explored and performed. For me, the compelling connection between steampunk and the digital humanities occurs in the circuit between cultural forms of self-fashioning dreaming of different histories and the technological forms of anachronistic tinkering that go with them. Steampunk imagines a technological and cultural world in which polycentric alternatives to chrononormative discourse can occur.

[24] While some of the less informed responses to the questions I posed to steampunk fans ignored the microaggressions and outright oppression many people experience everyday, the optimistic tone of the most progressive respondents caused me to wonder what a queer reparative digital humanities might look like. For me, steampunk offers two methods for imagining this practice. First, it complicates the chrononormative paradigm of digital humanities practice, in which scholarship homogenizes technological experiences in the form of specific applications, technologies, and methodologies. While it is important for DH scholars to understand the latest trends in technology, it is also imperative that researchers recognize the place of the historical, the inoperable, and the impossible to challenge the idea that all that matters in the field is efficiency, monetization, and the future. Further, it is important to understand how technological infrastructures – in Kazys Varnelis's words – do "not so much supercede old ones as ride on top of them, forming physical and organizational palimpsests, [...] and over time these pathways have not been diffused, but rather etched more deeply into the urban landscape." The notion of a homogenous technological future is only ever a heteronormative attempt to suppress the obsolescent, alternative, or queer technologies that fade from our historical imagination.

[25] Lee Edelman might have us say here, "fuck the future," and yet it is to Muñoz that I feel we must turn when thinking about chrononormativity: it isn't the future or the past (or the alternate past) that we should be wary of, but the idea that all of them are derivable from unchanging notions of the present. "What we need to know is that queerness is not yet here but it approaches like a crashing wave of potentiality," Muñoz argues, "[...] Willingly we let ourselves feel queerness's pull, knowing it as something else that we can feel, that we must feel" (185). Technology has its own version of chrononormativity, and the technologies that achieve market dominance aren't always the ones that are the easiest or the best to use. The media archaeology and critical making movements have made important strides in leveraging the creation of anachronistic devise to create hands-on reflection about the past. But the digital humanities needs more culturally informed materialist experiments to better understand technological difference rather than allow the streamlining of a complex digital ecology by grant-funded projects pointing to newer and newer digital products. The MOOC debate of 2011-2012 is a good example of how the excitement of present-day developments can obscure the broader historical work done in the digital humanities. While few digital humanities scholars embraced MOOCs with complete enthusiasm, the debate did become shorthand for digital humanities work — particularly in the "dark side of the digital humanities" panel at the 2013 Modern Language Association Conference in Boston. Wendy Chun remarked in the panel that her critique "is not directed at DH per se" but that the vapid cruel optimism behind "the blind embrace of DH (***think here of 'The Old Order Changeth***) allows us to believe [...] that the problem facing our students and our profession is a lack of technical savvy rather than an economic system that undermines the future of our students." Blindly embracing a future served up to us by shiny gadgets and cynical capitalists is very different from queer activists using radical difference and shared vulnerability to chart a different course for one another.

[26] Second, steampunk's utopianism can be culturally and historically naïve, but its welcoming atmosphere is also a real alternative to the retrograde antirelationality rampant in online Twitter discussions about the digital humanities that masquerade as cultural critique and Twitter activism. Bethany Nowviskie's 2012 post "Don't Circle the Wagons" mentions that despite the many cultural issues emerging in the wake of "the rise of the brogrammer" and the — certainly sexist — idea that everyone needs to learn to code, "I've been watching an increasing number of women in my Twitter circles shut down perfectly civil and earnest conversation by accusing interlocurtors of 'mansplaining' to them." Such examples have multiplied in the three years since Nowviskie's post, with a number of prominent digital humanities scholars quitting Twitter as a result of the hostility. Michael O'Rourke, in his work surrounding the feminist slut-shaming of Duke University student Belle Knox who works in the pornography industry to pay for college, has called the phenomenon "Mean Girl Feminisms." "With the emergence in the third wave of ever faster, more accelerated feminisms, on blogs, twitter, instagram, vine, shapchat and other social media we have witnessed—as Knox has written in several places—greater and greater shaming by feminists of other feminists who in their eyes are revolting (in every sense)" (21). To be clear, cultural critique has an important place in the digital humanities, and a phrase like "mean girl" carries gendered connotations that don't account for the myriad ways calls to civility are used to shut down conversation or the gendered violence underlying many of these exchanges. Still, the idea that critique can only come from an individualized identity position and that scholarship is a zero-sum game parallels the feminist bullying received by Knox and other sex workers. Each points to an idealized anti-relational identity position — and appropriates the accelerating computational temporality of Twitter — to own critique and shame other voices with the intention of silencing them.

[27] As an alternative, let's consider Margaret Killjoy's brilliantly utopian introduction to The Steampunk's Guide to Sex:

[W]e're not telling you that you have to tight-lace your corset to be a proper steampunk. You don't have to be into BDSM or kink at all. And you know what? Despite everything society has told you again and again, it's okay to be asexual. [...] What does it mean to be both a steampunk and a sexual creature? This is something we intend to explore, but believe me, it's not something we have any interest in defining. (7)

Killjoy's appeal to the "we" of relationality and the idea of exploring sexuality rather than defining it connects with Muñoz's invitation to take ecstasy with him in the final chapter of Cruising Utopia. "Take ecstasy with me [...] becomes a request to stand out of time together," says Muñoz, "to resist the stultifying temporality and time that is not ours, that is saturated with violence both visceral and emotional, a time that is not queerness" (187). We should not underestimate the "what if?" spaces constructed by groups of queer steampunks passionately invested in experimenting with the heterosexist past in order to imagine alternative possibility spaces. Even if these spaces are failures, they are invitations to declare that another world is possible. Cultural critique has an important place in these conversations — but so does the use of alternative communities for imagining speculative forms of queer technology. These forms of speculation can help uncover the technological and critical dependencies etched into our institutional imagination, and help us think them otherwise.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Nancy. Fiction in the Age of Photography: The Legacy of British Realism. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002.

Bartnett, Fiona M. "The Brave Side of Digital Humanities." Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 25.1 (2014): 64-78. Print.

Belojevic, Nina. "Designing a Case for a Kit." The Maker Lab at the University of Victoria. 6 November 2014. Web. 11 February 2015.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke UP, 2011.

Berlant, Lauren. "Cruel Optimism, Becoming Event: A Response." 10 December 2012. Web. 8 February 2015.

Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. "What Does Queer Theory Have To Teach Us about X?" PMLA 110 (1995): 343-49. Print.

Burdick, Anne, Peter Lunefield, Johanna Drucker, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp. Digital_Humanities. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2012. Print.

Cecire, Natalia. "Introduction: Theory and the Virtues of Digital Humanities." Journal of Digital Humanities 1.1 (Winter 2011). Web.

Chun, Wendy. "The Dark Side of the Digital Humanities — Part 1." Thinking C21: Center for 21st Century Studies. 9 January 2013. Web. 9 February 2015.

Clayton, Jay. Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2003. Print.

Dellamora, Richard. Victorian Sexual Dissidence. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1999. Print.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke UP, 2004. Print.

Florini, Stefania. "The Aesthete, The Dandy, and Steampunk, Or Things As They Are Now." Like Clockwork: Essays in Steampunk. Minneapolis, U of Minnesota Press, Forthcoming. Print.

Freedgood, Elaine. The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2006. Print.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham: Duke UP, 2010. Print.

Gaboury, Jacob. "On Uncomputable Numbers: The Origins of Queer Computing." Media-N: Journal of the New Media Caucus CAA Conference Edition (2013). Web.

Galloway, Alexander. Laurelle: Against the Digital. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 2014. Kindle File. Web.

Garelick, Rhonda. Rising Star: Dandyism, Gender, and Performance in the Fin the Siècle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1998. Print.

Hager, Lisa. "Queer Cogs: Steampunk, Gender Identity, and Sexuality." Web. Tor.com. N.p., 4 Oct. 2012. Web. 20 May 2014.

Hancock, Charity, Clifford Hichar, Carlea Holl-Jensen, Kari Kraus, Cameron Mozafari, and Kathryn Skutlin. "Bibliocircuitry and the Design of the Alien Everyday." Textual Cultures: Texts, Contexts, Interpretation 8.1 (2013): 72-100. Print.

Hertz, Garnet, and Jussi Parikka. "Zombie Media: Circuit-Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method." Leonardo 5.5 (2012): 424-30. Print.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York UP, 2013. Print.

Johnson, E. Patrick. " 'Quare' Studies, or (Almost) Everything I Know About Queer Studies I Learned from my Grandmother." Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology. Ed. E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Lenderson. Durham: Duke UP, 2005. 124-159. Print.

Killjoy, Margaret. "Introduction: Learning About Sex." A Steampunk's Guide to Sex. Ed. Professor Calamity. Oakland: Combustion Books, 2012. 1-7. Print.

Kim, Dorothy. "The Rules of Twitter." Hybrid Pedagogy: A Journal of Learning, Teaching, and Technology. 4 December 2014. Web. 11 February 2015.

Kirschenbaum, Matt. "What Is 'Digital Humanities,' and Why Are They Saying Such Terrible Things About It?" Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 25.1 (2014): 46-63. Print.

Koh, Adeline. "Niceness, Building, and Opening the Genealogy of the Digital Humanities: Beyond the Social Contract of Humanities Computing." Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 25.1 (2014): 93-106. Print.

Kraus, Kari. Hopeful Monsters: Computing, Counterfactuals, and the Long Now of Things. Boston: MIT, Forthcoming. Print.

Matthews, Christopher. "A Radical's Legacy: Emma Goldman Lives On at Occupy Wall Street, and on the Rental Market." The Local East Village, 22 Dec. 2011. Web. 20 May 2014.

Miller, Monica L. Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Durham: Duke UP, 2009. Print.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NYU Press, 2009. Print.

Nowviskie, Bethany. "Don't Circle the Wagons." noviskie.org. 4 March 2012. Web. 9 February 2015.

O'Rourke, Michael. "Belle Knox and the Making of the Indebted Woman." Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities. Skopje, Macedonia. 24 January 2015. Invited Lecture.

Parikka, Jussi. What Is Media Archaeology? Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2012. Print.

Pho, Diana. "Politics in Steampunk — A Sampling (aka 'Why It Matters')." Web log post. Beyond Victoriana. 06 Apr. 2013. Web. 20 May 2014.

Pho, Diana. "Punking the Other: On the Performance of Racial and National Identities in Steampunk." Like Clockwork: Essays in Steampunk. Minnesota: U of Minneapolis, Forthcoming. Print.

Powell, Philip S. "Re: Steampunk, Gender, and Sexuality." Message to Roger Whitson. 2013 Apr. 4. E-mail.

Powell, Philip S. "Steampunk POC: Phil Powell (Mixed Race: German, African, Cherokee)." Interview by Jaymee Goh. Silver Goggles. 2 Mar. 2012. Web. 20 May 2014.

Ramsay, Stephen. "DH Types One and Two." Web log post. Stephenramsay.us. 03 May 2013. Web. 20 May 2014.

Ratto, Matt and Megan Boler, eds. DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media.

Rogers, Ashley. "Con Life, Gender, and My Hypothetical Genitals." Web log post. Beyond Victoriana. 27 June 2012. Web. 20 May 2014.

Scheinfeldt, Tom. "The Dividends of Difference: Recognizing Digital Humanities Diverse Family Tree/s." Web log post. Found History. 7 Apr. 2014. Web log post. 20 May 2014.

Schulman, Michael. "Generation LGBTQIA." The New York Times. 9 Jan. 2013. Web. 20 May 2014.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke UP, 2003. Print.

Shahani, Nishant. Queer Retrosexualities: The Politics of Reparative Return. Bethlehem: Lehigh UP, 2012. Print.

"SPM Contributor Miriam Roček Arrested At #OWS Again." Web log post. Steampunk Magazine, Web. 20 May 2014.

Siegel, Lisa. Governing Pleasures: Pornography and Social Change in England, 1815-1914. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2002.

Stross, Charlie. "The Hard Edge of Empire." Web log post. Charlie's Diary. N.p., 27 Oct. 2010. Web. 20 May 2014.

Thomas, Kate. Postal Pleasures: Sex, Scandal, and Victorian Letters. New York: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

Varnelis, Kazys. "The Centripetal City:." Cabinet: 17 (Spring 2005). Web.

West, Lindy. "What Happened When I Confronted My Cruellest Troll." The Guardian. 2 February 2015. Web. 11 February 2015.

Notes

- This piece is the result of many conversations, drafts, and readings with generous scholars and good friends. I'd like to thank Katherine Harris and Jacqueline Wernimont for working with me on early drafts of this piece; Jaymee Goh and Diana Pho for introducing me to the steampunk community and helping me to articulate the politics of fandom; Lisa Hager, Ashley Rogers, Philip Powell, and Miriam Rocek for contributing their thoughts on queer steampunk fandom and activism; Nishant Shahani for assisting in my navigation through queer theory; and Steven E. Jones, Michael O'Rourke, Roopsi Risam, Davin Heckman, Helen Burgess, Ellen Berry, and Carol Siegel for their comments and encouragement about the work.

- Scholars have suggested several starting points for alternative genealogies. Tom Scheinfeldt has pointed to the Columbia Oral History Office and the Library of Congress's Archive of American Folk-Song as an alternate genealogy for the public ethos behind many digital history projects. Similarly, Stephen Ramsay divides the discipline into DH 1, including early 1990s work in TEI and humanities computing; and DH 2, emerging around 2008 and representing a broad array of practices and a "revolutionary disposition" regarding digital practices. Fiona Bartnett suggests reorienting the focus away from specific scholars and conferences and toward projects that foreground the field's continually changing identity.

- See also what Nishant Shahani's calls "queer retrosexualities, which to him "defines much of the queer experience" and includes "myriad manifestations—of returning to the primal scene, of belated recognition, of nostalgic mourning, of moving backwards in time, of thinking about the pastness of the future" (1). His introduction tracing the genealogies of reparative queer theory is particularly important to this project.

- As Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner argue, queer theory shouldn't be identified exclusively with LGBTQ issues, instead what they call queer publics "make[s] available different understandings of membership at different times, and membership in them is more a matter of aspiration than it is the expression of an identity or a history" (344).

- Jenna Leeds pointed out to me in conversation the relevance of telegraphic cryptography to the development of coded language for queer communities in the nineteenth century and how that impacts the way Hardy develops the relationships between the women in A Laodicean.

- Miller appropriates, here, E.

Patrick Johnson's notion of "quare" as a racialized version of queer. For

Miller,

"Quare" [is] a way to critique stable notions of identity and, at the same time, to locate racialized and class knowledges. [...] I want to maintain the inclusivity and playful spirit of 'queer' that animates much of queer theory, but I also want to jettison its homogenizing tendencies. As a disciplinary expansion, then, I wish to "quare" "queer" such that ways of knowing are viewed both as discursively mediated and as historically situated and materially conditioned.[...][Q]uare studies acknowledges the different 'standpoints' found among lesbian, bisexual, gay, and transgendered [sic] people of color differences— differences that are also conditioned by class and gender" (127).

- Hancock et al. discusses "possibility spaces" specifically in the context of reflective design, which "helps us discover the fault lines in the objects, artifacts or systems being explored [...] and in so doing allows us to imagine them otherwise" (76).

- You can see the entire Storify of Pho's conversation here: «https://storify.com/rogerwhitson/beyond-victoriana?utm_source=embed_header».

- Galloway is referring here to the fact that digital images are made up of pixels or "picture cells," which are placed onto a raster image much like a grid, creating a conglomerate image from smaller structures.

- See Edelman's use of the polemic form in No Future, along with his argument that queer theory should engage the negative "[n]ot in the hope of forging thereby some more perfect social order—such a hope, after all, would only reproduce the constraining mandate of futurism, just as any such order would equally occasion the negativity of the queer—but rather to refuse the insistence of hope itself as an affiramation, which is always affirmation of an order whose refusal will register as unthinkable, irresponsible, inhumane" (4).

- The turn towards conjectural and speculative forms of inquiry is also aligned with Muñoz's insistence on thinking elsewhere. For instance, Kari Kraus argues that the digital humanities can provide a forum for speculative engagement with the future. Her version of this future, however, is imagined as "saturated with durable artifacts in altered or decayed states that survive from earlier times, as well as copies, versions, emulations, duplicates, adaptations of prior cultural productions" (4).

- For more information on critical making and its political interventions, see Matt Ratto and Megan Boler's DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, where they separate hacktivism from maktivism by saying that the latter "necessarily involves materiality, or matter (i.e., that which has mass and occupies space, e.g., solids, liquids, and gases), and is therefore not limited to merely writing or modifying computer programs." Parikka's What is Media Archaeology? similarly calls for "using mixed materials in assembling new forms of media apparatuses that are outside the mainstream understanding and yet tap into the very scientific bases into which modern storage and communication media are built."

- Chun's invokes here Lauren Berlant's notion of "cruel optimism," which is defined by Berlant as "a relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility" that "provides something of the continuity of the subject's sense of what it means to keep on living on and to look forward to being in the world." She goes on to explain that "[c]ruel optimism is the condition of maintaining an attachment to a problematic object in advance of its loss" (Cruel 21). Such a critical approach to certain forms of optimism might seem to contradict my embrace of Muñoz's utopian impulse, and yet, Berlant herself reads Muñoz's utopianism very differently in a 2011 event about her book Cruel Optimism at NYU. Here she references Muñoz's work as rescuing "the defaced past for a better life in an elsewhere that is affectively present but yet unmaterialized" and suggests that her own work is similar, because it sees criticism as "a craft for inciting the world to be otherwise than it is" (Becoming 1).

- As Dorothy Kim points out, there are also some good moments of critique on Twitter in which privilege is pointed out. "The relocation of Twitter — from the bucolic image of conversations with neighbors in the 'American Dream' single-family neighborhood to loud Broadway (clearly envisioning New York City) — is a statement about digital white flight. However, the neighborhood in the eyes of these white male pundits was always imagined as safe, suburban — by default — white, and upper-middle class." Yet I also distinguish between the work of activists complicating the dreams of a gentlemanly elite desiring a purified white male (heteronormative) space and the actions of trolling — which often impact feminist activists. The trolling of feminist video game blogger Anita Sarkeesian, for instance, included many public threats on Twitter. Former Jezebel contributor Lindy West wrote in The Guardian about a troll who created a Twitter account impersonating her dead father. As West recounts "The name on the account was 'PawWestDonezo,'" West recounts, "because my father's name was Paul West, and a difficult battle with prostate cancer had rendered him 'donezo' (goofy slang for 'done') just 18 months earlier. 'Embarrassed father of an idiot,' the bio read. [...] His location was 'Dirt hole in Seattle.' Such examples require us to understand Twitter not only as a public space, but also as a space that violently and volumetrically intrudes upon the private lives of activists — particularly feminist activists, queer activists, and activists of color — through bullying and harassment.

- By phrasing the digital humanities as a possibility space, I hope to draw off of Matt Kirschenbaum's use of John Unsworth's sense of the digital humanities as a "concession" used to "consolidate and propagate vectors of ambiguity, affirmation, and dissent" (63). The point Kirschenbaum makes that "definitions of digital humanities are commonplace and easy to come by," parallels the propagating initialism for queer communities that began as LGB (for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual) and was expanded over years to become LGBTQIA. See Michael Schulman's article "Generation LGBTQIA," particularly the quote from Jack Halberstam who says that "[w]hen you see terms like L.G.B.T.Q.I.A.,[...] it's because people are seeing all the things that fall out of the binary, and demanding that a name come into being."