Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

Beyond Thinking: Black Flesh as Meat Patties and The End of eating Everything

Theodora Danylevich

PDF

PDF

Tropics of visceral refusal

In an interview with Frank B. Wilderson, III, published as "The Position of the Unthought," Saidiya V. Hartman draws the contours of a narrative aporia in the writing of American cultural history: "on the one hand, the slave is the foundation of the national order, and, on the other, the slave occupies the position of the unthought" (184-185). In other words, the brutality that is foundational to the nation is not possible to encounter in the realm of thinking. The history of such violence is not accepted into the official white-supremacist-historical archive, except as a sanitized past: commodified as something that has been "overcome." In the present discussion, I use the phrase "black flesh" to denote this foundational brutality, and the violence of being "unthought." Building upon Hortense Spillers's use of "captive flesh" to denote the historical slave, "black flesh" signifies for the historical slave and for her "afterlife of slavery," as Hartman has famously put it. Black flesh here also significantly accrues the sense of "post-slavery" as articulated by Christina Sharpe: "subjectivities constituted from transatlantic slavery onward, and connected, then as now, by the everyday mundane horrors that aren't acknowledged to be horrors" (Sharpe 3). In this violenced kinship, flesh can be understood to figure an inner register of violence against African-American and diasporic black subjects—today, and in the unthought annals of history.

I do not seek to make sweeping claims about the semiotics of blackness or flesh. Rather, I encounter flesh as a contested conceptual site for thinking through the repercussions of cultural and visceral violence in Afro-Pessimist discourses. Flesh, as an archival register, comes to us in Spillers's discussion of the marks of violence on the captive body: "lacerations, woundings, fissures, tears, scars, openings, ruptures, lesions, rendings, punctures" conceived as "hieroglyphics of the flesh." This fleshy archive is a foundational and cryptic script to which Spillers designates a "cultural vestibularity," in the sense that the culture of sanctioned violence passes through and requires this passage-chamber of "undecipherable markings"—of unthought flesh, "whose severe disjunctures come to hidden to the cultural seeing by skin color" (67). Violently inscribed with and then left violently unthought by culture, this history inscribed on flesh is relegated to a "lower level in the hierarchy of memories." As a result of this encryption, the continued violence against black bodies is sanctioned and "justified." Deadened, silenced, sanitized, and commodified by cultural grammars of denial, black flesh is yet vital and alive as an inner register of antiblack violence, dense with the traumatic energy of erasure that is its imposed grammar.

To name a few contributions in recent writings in and around discourses of Afro-pessimism, black flesh is a zone of suffering; an assemblage of resistance and alternate world-making; a designation of accumulation and death; and it is a resonance of mystical capaciousness. In this conversation, black flesh is a charged and dense "in-the-break-ness," where the wounding is as perpetual as is "the fragility of healing" (Moten 753). As a conceptual vehicle and a visceral reality, flesh exerts a dense gravitational pull for thinking black subjectivity in its ambivalence as a site of annihilation and potentiality, not unlike a black hole. The trope of the black hole, or "(w)hole," both invisible to the eye and incredibly dense, is an apt figuration for these ambivalent registers and significations of black flesh in the greater context of historical and textual authority. Found at the epicenter of most galaxies observed, black holes are considered foundational to the structure and texture of our cosmic world. Discursively positioned as an invisible, forgotten void, black flesh is actually dense and full, and central to the socio-political fabric. Foundational and unthought, black flesh operates as a black hole in the terrain and fabric of thought—a terrifying necessity.

Jared Sexton writes that the multiple modes and directions of analysis and questioning in the context of black studies "lead everywhere, even and especially in their dehiscence" (7). "Dehiscence" in the conceptual and the visceral ground of flesh has two divergent meanings: First, wound dehiscence is a surgical complication in which a wound comes apart at the site of its surgical sutures – flesh that opens up at the seams, along the fault lines of the discourses that would seek to keep it sanitized and under wraps: a wounding history that refuses its sutures—refuses silencing. The second biological meaning of dehiscence is one of generative potentiality: that of the rupture of a female's ovarian follicle in the process of ovulation. This ambivalence of signification animates a sense of wounded flesh, and, simultaneously, of pregnant flesh: a fleshy register of violence as the wound that refuses to heal, and also a rupture of generative potentiality in the reproductive cellular kernel of flesh.

Both a re-materialization of past injury and violence in the present body, and the release of a potential future reproduction of one's fleshly records in a new body, dehiscence can be understood as a visceral speech-act. That is to say, dehiscent black flesh here is a dense and felt communication where the violently unthought history of violence "speaks" by way of the senses. Disrupting the skin of the universe and destabilizing the geometries of enlightenment thought with its force field as opening and rupture, black flesh as a dis-eased, animate register of unthought foundational violence "speaks itself." Just as a black hole's primary means of detection is by its distortion of the gravitational orbits of those visible stars around it, dehiscent black flesh communicates by the decentering of one's senses with the revulsion impulse such that one feels its horror—evoking a visceral reaction of disgust and refusal. The grammar of black flesh continuously turns on the tropic of visceral refusal, toward a manifestation of the "history of the present" as a felt disorientation. The disgust or aversion-response elicited is an inarticulate experience: It is not logical, and thus its expression and evocation is a disfiguring language structured in a non-logical grammar, beyond thought.

Can the meat patty speak?

My reading of two filmic texts below moves toward the experiential encounter with black flesh as an archival and communicative entity that is animate in "Meat Patties," a short YouTube video coming out of an Alabama prison, and The End of Eating Everything, an art film that has been shown in galleries and film festivals. Both films figure a mass of diseased, processed flesh as antagonistic protagonist, an animate archive of the unthought as meat patty in one, and as grotesque fantastical creature in the other.

"Meat Patties," a 4-minute archival missive filmed on a cellphone camera from inside of the white walls of a prison as a part of the Free Alabama Movement (FAM)'s social media initiative, might be encountered primarily as a wound dehiscence—an opening-up of black flesh along the seams of its silencing. At the same time, the wide distribution of the recording may be understood in terms of a follicular, reproductive dehiscence.

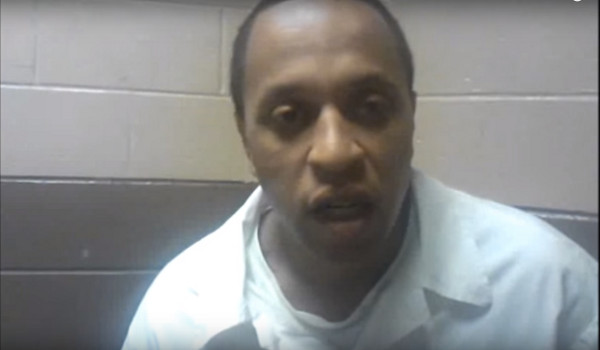

FAM is a collective working to dismantle the slave empire of US prisons from within, primarily by means of labor strikes and by using the internet to publicize unlivable prison conditions. "Meat Patties" was widely disseminated in 2014 by a Salon.com article with the byline of breaking news about the prison labor strikes in Alabama. The video shows spokesperson, prisoner, and organizer Melvin Ray documenting and describing in gross detail the poorly-cooked meat patties of questionable substance that they are given as food, and expected to eat. This documentation is intended to mobilize awareness of prison conditions whitewashed by mainstream media, and also to combat the discursive dehumanization of the prisoners themselves. Taking apart and exposing undercooked and rotting flesh for the camera, Ray expresses the disorientation and refusal: "we don't know what it is, we don't eat it, we can't eat it."

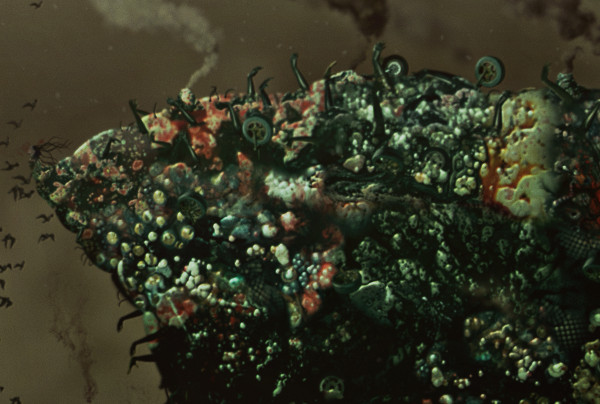

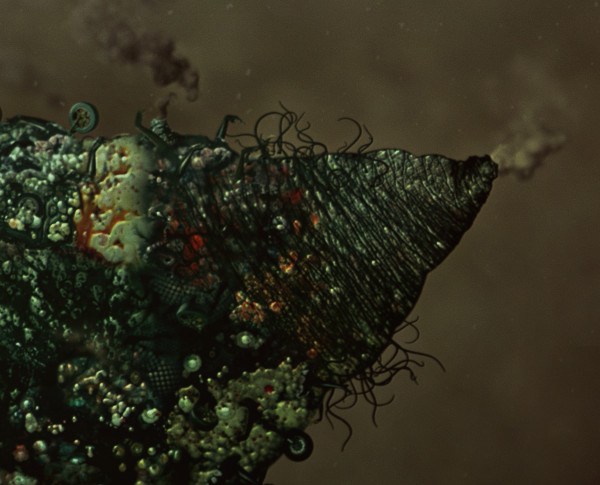

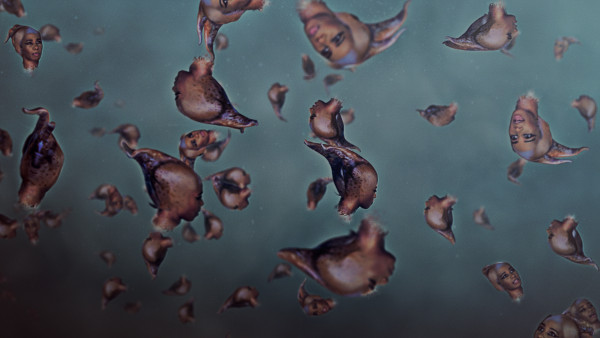

The End of Eating Everything is an 8-minute-and-ten-second stop-animation and CGI art film, painstakingly produced by the artist in collaboration with a design team and singer-songwriter Santigold as actress. The film is the concluding piece to a "fantastic journey"-themed art exhibit, by Kenyan-American collage and multimedia artist Wangechi Mutu. The creature in The End of Eating Everything renders the register of black flesh visible in an animate body that is an enormous mass whose surface bears a dense layering of limbs, machine parts, erotic attributes, and disease spores. Projected and playing as a continuous loop from the white walls of the art gallery space, this recording both cuts the figure of a dehiscent wound in the creature's flesh, and traces a reproductive follicular dehiscence, as the creature on the screen ruptures, giving way to a growing crowd of tadpole-like severed yet living and speaking heads that come to populate the screen. Mutu identifies with Afro-futurism, citing Sun-Ra as an inspiration, yet she also speaks about her work as a visual testament to the debilitating impact of postcolonial violence in her native Kenya. Speaking about her film in an interview, Wangechi Mutu explains, "I want [viewers] to smell it —I want them to really know that where they're at something has gone awry—something is wrong" (Artnet).

The divergent contexts of these two fleshy black holes in white walls—on one's computer screen as a missive from "the hole" of solitary confinement by a southern black man, and projected onto the white wall of an art gallery in Brooklyn by an Ivy-league-educated woman of Kenyan background—offers a view of the impact of anti-blackness as a violence of "cultural seeing" that cuts across gender and class. That is to say, anti-blackness is a "cultural seeing" wherein the perception of skin color covers over, hides, and justifies the "severe disjunctures" and hieroglyphics of black flesh. The two filmic recordings offer dehiscent fleshy expressions of the history of anti-black violence as a persisting "history of the present." Their dehiscences show the filth of anti-blackness as it accrues onto and adheres to fleshy surfaces: the violences of cultural seeing materialized. By such materialization, "Meat Patties" and The End of Eating Everything evoke visceral disorientation and disgust that generate sensory confusion and de-centering, destabilizing the ground of and challenging the logics of cultural seeing.

"Meat Patties": evidence and refusal from the inner slave empire

Seeking to set the stage for the discursive field around a prison revolt in the form of a nonviolent labor strike, Melvin Ray shows and performs a physical analysis and excavation of viscerally revolting meat patties. Where one might anticipate a list of grievances and a detailing of conditions, the focus of this video circulated in accompaniment to the news story of a prison labor strike, has meat patties as its main event and focus of discussion. Due to the sound being very weak in the YouTube file, you have to strain to hear Ray's voice as he speaks. Due to a combination of the sensory strain and a function of the camera being trained on the burger patties rather than the bodies of the prisoners, the meat patties are effectively a proxy mouthpiece for Ray and his co-prisoners, their grievances, and their revolt.

With eight patties laid out on the table, Ray selects one, about which the frame of view tightens until the patty takes up the frame. The patty is mottled and discolored, including green and pink and brown on the meat, as well as some charred parts.

Ray's hands pick up another patty, which is in fact two patties stuck together—"a double-patty"—and he pulls the mass of processed meat apart to show an alarmingly raw and pink fleshy interior. Laying this meat open, he proceeds to slowly and deliberately excavate mysterious pieces of gristle from inside the patty that may be gravel, plastic, and/or bone or cartilage, his hands digging through half-cooked flesh. This is a tactile penetration and analysis, an intimacy and a violation.

The disturbing and pornotropic opening-up of the meat patty into two sides of raw flesh is multiplied in the video as Ray repeats this scenario with several more patties, which grow grotesquely larger as the camera approaches. After Ray is through with the patties, he carefully stacks all of them neatly into a dustpan that is being held waiting by another attendant inmate, whose brown hand and forearm are all that the camera otherwise captures.

Thus stacked in a dustpan, following Ray's penetrative analysis, it becomes uncomfortably palpable that the meat patties are not only a mouthpiece for this particular video missive of protest, or merely an archive of grievances: they are body doubles for Ray and his co-inmates.

Considering the revolting scenario of this video on the terms of a labor strike—of inmates in revolt, conveyed by revolting meat patties—one might see the refused and revolting meat as a concrete rendering of the thoroughgoing violence done to the inmates' own physical and political flesh. Beyond the exposure of the vile eating conditions of inmates, the meat patties, figured here as refused flesh, are a visceral metaphoric—metonymic, even—for the dehumanization and functional enslavement of the inmates. The meat patties' accumulation into an undifferentiated mass that has been indifferently preserved, inconsistently cooked, fed back to itself, and then discarded as hazardous waste, is both the inmates' flesh and it is the food that does not sustain them, and might in fact kill them. Ray's mumbled "...bust this one open," as he goes to open up a set of double patties, enacts a turning inside out of the cultural text and the violence of anti-blackness: Ray's gesture and words in turning the meat patties inside out stands in for the way in which the recording itself enacts an "inside out," where prison, as a hidden slave empire, is a deep interior of black flesh that is being opened, to show its sickness, rawness, pervasiveness. The flesh is inscribed with the history of the present, making visible "the marks of a cultural text whose inside has been turned outside" (Spillers 67).

The End of Eating Everything: disorienting grammars and economies of flesh

The End of Eating Everything shows a creature with a visual and allegorical affinity to the meat patties in the FAM video. The film has as its visual centerpiece and central protagonist an enormous animated, living female-headed fleshy mass that moves in an amoeba-like fashion, and is mottled with her own "gristle" of pockmarks, including uncannily moving arms, spinning wheels, and what appear to be marks of disease and infection on her surface. These are accumulated adhesions of the impact of cultural seeing of skin color, on and as the creature's body; black flesh as unthought history materialized. The film's creature is a disorienting figure introduced by a short poem that performs a grammar of refusal; fugitive from sense, time and place. The creature's massive body is at once terrifying and seductive. Its surface and shape and size variously manifest an animate archive of the effects and accumulated waste that are testament to the continuing after-lives of slavery, colonial violence, and global industrial and post-industrial capital. On her flesh is the indelible excrement of the extreme violences of anti-blackness in the history of the present, then and now. A fleshy synchronous palimpsest exhibiting the violences of "cultural seeing," playing on a repeated loop in a darkened corner of a museum gallery space, the creature is a deracinated cinematic organ of memory that relentlessly draws viewers in and assaults them with her archive – a black hole in a white wall, a haunting time capsule, synchronous, and on repeat. The creature is a traumatic register of unthought violence, like the meat patty in the FAM recording, but Mutu's film enacts a critical reversal from the previous video: the refused mass of unthought black flesh is shown to be eating. Where Ray and his co-prisoners were refusing to eat patties of revolting flesh that are ultimately allegorical for themselves, Mutu's creature violently cannibalizes black flesh as figured by a flock of black birds. A disorientating economy of black flesh is at work in both The End of Eating Everything and "Meat Patties," with the unsteady switchpoint of the alternately captive-fugitive and dangerously predatory masses of flesh. This disorienting autophagic economy is framed and supported by the unfolding of text in Mutu's film—a poetic text composed of intertitles, preceding the creature's scene of feeding. In it, a fugitive sense is conveyed by statements that double back on themselves, enacting this sense of captivity inside of black flesh and a struggle to both show black flesh and to escape.

As the film fades in, the title appears, hanging in a post-apocalyptic, rust-colored sky, with a fine flecky snow of ashes floating in the air, ambient with industrial sounds and shrieks. A flock of birds comes into view, passing through and shattering the title, which falls out of the frame with a loud sound of breaking glass: a title of refusal, shattered.

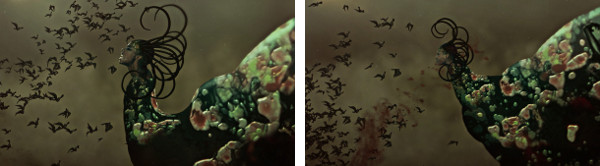

The birds take over the screen, with the ruddy and smoky clouded background and a constant flurry of ash animating the air. Out of the right side of the screen, the creature's face comes into view slowly as the camera pans out a little bit. She glides toward the birds, her attention and gaze focused on them. Viewers then encounter her medusa-like dreadlocks that behave more like a cluster of long and thick rodent tails, coiling and uncoiling as the creature moves, agentic of her motions.

She and the birds are engaged in a tense but almost tender dance as they advance around her face and draw back again while she is still, watching, sniffing. It is here that the poem, sketching an indeterminate and monstrous "it," unfolds as a series of intertitles at the bottom of the screen. The intertitles are rust-colored, as though written in dried blood. In a serif font, a typeface ordinarily reserved for print, these written words are evocative of an archival effect, unfolding beneath the creature's bust, indicating an intended visual speech-bubble or representation of her voice or thoughts. The message is difficult to decipher, not accommodating to the grammar of sense.

I never meant to leave

I needed to escape

And now it's so far

Who knows where?

It's been like this for a very long time...

It follows me, and I them

Hungry, alone and together.

The lines contain internal tensions and contradictions within themselves, and in relation to one another. In the first two lines, an uncertain departure and a need to leave are expressed; an indeterminate and distant location is the object of the following two lines; a vague sense of protracted time is set forth in the subsequent line; and a terrifying confusion of voice, object, and agent of escape are sketched in the closing couplet. This aporetic narrative stages a repeated autophagy of sense and agency. The lines turn in upon themselves, and the contingent materiality of the words, and ultimately of the creature's flesh, supersede known rules of grammar, logic, and meaning. A black-hole-like effect on sense in this poem frames and haunts the visual of dehiscent black flesh in The End of Eating Everything. Throughout the poem, and culminating especially at the end, shifting pronouns of subject and object "I," "It," "me," "them," create a constellation of vectors that scaffold a "different geometry" of thinking self. A nebulous sense of subjectivity and intersubjectivity expresses the disorientation of unthought constitutive historical violence. And while the creature is ostensibly seeking to flee an invalidating "It," which we ultimately come to understand is a part of the creature: her flesh, her nearest approximation of self.

Considered together, the opening pair of lines "I never meant to leave / I needed to escape" convey a departure and escape that is both necessary and uncertain. "I never meant to leave" expresses a disavowal of agency and a dispossession of intention, if indeed the departure or escape has been accomplished: While the line speaks from the first person "I"—a deictic of agency—it is immediately followed by "never meant to," negating the sense of agency and actionability that the first-person-singular speaking subject might normally accrue. "I needed" in the next line again expresses a compromised "I": not the certain, empowered, enlightenment-liberal speaking subject, this "I" both lacks agency and is expressing a state of neediness. The lines in this opening couplet are in the past tense and passive voice, and we are not given grammatical certitude of the actual completion of a flight from someone, something, or somewhere. On the other hand, this opening couplet contains an ironic gesture toward the nineteenth-century slave narrative genre, which was often framed by a validating statement from a white abolitionist "sponsor" who would aver the truthfulness of the account of the escaped slave, who then would proceed to narrate the ills of the institution, and their successful escape therefrom. In an ironic and corrective turn on the conventions of this genre, "I never meant to leave / I needed to escape" frames the narrative in her own voice, and conveys an account of longed-for escape that is ambiguously and tenuously achieved, if at all. Just as with the shattering glass of the title that proclaimed successful refusal and potential change by "the end of eating everything," the fugitive grammar of the opening lines here destabilizes the hope of—and marks the contours of—an uncertain escape, all while functioning as a portal for the fugitive subject to speak on her own behalf.

In the second couplet, "And now it's so far / Who knows where?" hints of certitude and hope are doubled back upon and thrown into question as the lines unfold: "And now it's so far" communicates a potential hope that the creature might in the present time, "now," find herself far away from that which she needed to escape. At the same time, the vagueness and unlocatability of "it" and "far" of the second clause, "it's so far," turns back to compromise the potential conclusive certitude of "and now." We get the sense that "it" is a placeholder for the undesirable and yet not known (to us, the audience) agent of the creature's need to escape. Yet, the location of "it" in relation to the creature's speaking "I" is not clear. "Who knows where," a vacuous rhetorical question, arrives in place of any elaboration on the determinacy of the subject "it," or the location of "far." "Who knows where?" augments the indeterminacy of "far," emphasizing the creature's incertitude of both the time elapsed nor her distance (or proximity) in relation to the object of her flight. In itself, "who knows where?" defuses the certitude of knowledge that "knows" might otherwise suggest by surrounding it with "who" and "where," forming a question that sucks its own knowledge into itself: a black hole of unanswered questions and pronouns without referent. The work of this grammar—fugitive from sense, nervous, always in motion, and set on destroying its own tracks—leaves us with an ominous "it" that is unlocatable and yet "so far." "Far" here also carries a possible implication of violent excess: whereas "it's so far" stands for the hope of a possible flight or escape from the harmful agent of the creature's objectification, a predatory "it" that is now "so far" is haunted by the notion of something that has "gone too far": an excess of violence that's gone on for too long. "It" thus simultaneously indicates a fantasy of hoped-for escape from an abusive state of depersonalization, disfranchisement, and death.

The line that follows, "it's been like this for a very long time...," with the appearance of the punctuation mark of the ellipsis, accrues to this reading of "far" temporal, spatial, and political affects. The time elapsed is indeterminate, though it is given breadth of expansion into the past and the future as "a very long time..." Here, the pronoun "it" correspondingly expands into a broad, general indeterminacy, absorbing into itself the foregoing, more potentially localizable "it." "Now it's" no longer holds a time or place that can be approximated, beyond the vast generality of the ellipsis. The ellipsis indicates indeterminate future continuation: "etcetera," or "and so on and so forth" are implicit in its trail, but not articulated. The ellipsis both suggests and covers over words that might else articulate unthought and ongoing histories. It would seem that "it" now stands for a condition of captivity—an abusive other/ing to be fled—that has persisted, with the graphemic ellipsis here operating as an agent of elision, of occlusion, simultaneous with its indication of repetition and continuation. "It" as the object of flight or departure—that which is being fled from—becomes more monstrous in its indeterminacy.

The most terrifying moment of the textual unfolding manifests itself in the lines that close the poem, and open out onto the I-creature's grotesque enactment and exhibition of black flesh in her feasting on the birds and in the appearance of her grotesque body: "It follows me, and I them / Hungry, alone and together." Here, "it" jarringly jumps to encompass a broader generality in its very localization and materialization as the creature, herself. In the symmetrical clauses of "It follows me, and I them," "it" becomes identified with "I" just as "me" becomes associated with "them." "Hungry, alone and together" articulates an affective constellation of a fugitive nervous system that is without a ground of self that can be separated from the violences directed against this self: "It" is inscribed in the hieroglyphics that constitute her flesh, a constitutive and inescapable monster. The failed escape, and the non-manifest leaving—all of the disorientation of sense in the preceding lines comes to a fore: she is being pursued by the amorphous and indeterminate agent of her need to escape, and this object of flight is attached to her, is her flesh. The hunted being is, in herself, the hunter-hunt/ed. The pretty fantasy-glass of utopic flight and exit—a fantasy tenuously and fleetingly upheld in the poem—shatters and falls apart and away, like the glass of the title of the film. It is after this line that the creature begins to feed on the birds.

As she feeds, more and more of her shape comes to occupy the screen, and a complete zoom outward of the screen shows the creature's grotesquely massive scale. The effects of "eating everything" become apparent as concretized in her body—a horrific and enormous yet seductively beautiful mass of flesh.

Populating and bringing to uncanny life the surface of her dense lump of body-mass, wheels squeak and spin slowly and freely, undead black arms protrude and wave slowly in a torpor, several blow-holes exude smoke, and cilia-like pubic hairs adorn her edges, anemone-like and pulsating. A mass of accumulated and her heterogeneously constituted flesh, her shape is suggestive of an island or a landscape contaminated by industrial waste and chemical burns and oil spills.

The creature also fashions herself as a fleshy mass allegorical of a ship from the middle passage into this dystopic Afrofuturistic mothership. Simultaneously, she exhibits her injured flesh, reproduces a pained history of unthought and disavowed flesh, and seeks to envision something that goes beyond: a fleshy "fantasy in the hold" (Moten 2013, Wilderson 2008).

A filmic climactic petite-mort pornotrope of racist capitalist white supremacy, she is a sick and disturbing pornographic money-shot. She is also propelled forward by a massive pussy at her rear that expands and contracts while expelling smoke, or gas: a farting black hole with a concentration of pubic-hair-like cilia waving around its perimeter that is perhaps more precisely at once anus and vagina.

The film's creature as archive and memory, inasmuch as she presents a cinematic organ of memory, is thus also a biological site of reproduction and the terminus of the digestive tract: the end of eating. Her multivalent large fleshy mass may just as well be a diseased and free-floating massive uterus. Expelling gas to move forward, and feasting on and destroying her companion birds as she does so, the creature enacts an obscene exhibitionism of "progress" by way of a noxious and unsanitary "end of eating everything." Feeding and farting to sustain the questionably-viable life that she carries inside, she is a self-propulsing, sickly, mottled, farting trash island sex organ. This is her stinky potentiality—the visceral wish that Mutu expressed in saying that she wanted viewers to "smell it...to really know that where they're at something has gone awry—something is wrong": grossly, terribly wrong.

In a dramatic and lush gesture of refusal, the creature's body disappears in a cloud of these gaseous expulsions that swirl over her. This view fades into a placid blue sky with clouds, and small, disembodied, tadpole-like heads gradually come to fill the screen, whooshing slowly into the frame in a quiet torpor. It would appear that the creature had both imploded and multiplied, or given birth. Each of these heads has a face identical to that of the creature, and is propulsed by a tadpole-like tail, in place of the mass of coiling locks that animated the former creature's head. As the image of the floating heads becomes more focused, bits of electro-blood suspended below the neck of each head make it apparent that this is a sea of heads that appear to have been forcibly severed from their flesh. They are all inaudibly speaking: lips moving, though viewers cannot hear what they're saying. This scene is both one of the consequence of slaying the toxic beast that happened to be your pregnant self, and a view of your potential speaking reproduction, with an uncertain text, and a message that appears not to be transmissible, at least by words that are easily discerned.

As with Melvin Ray's voice that is very difficult to hear in "Meat Patties," these always-already severed, brown-skinned talking heads, whose voices are inaudible, compel a focus on flesh as a dehiscent zone of visceral protest, critique, and communication that defies both reasonable sense and the linear temporality of history. As with the meat patties in the other film, the creature's flesh is a hazard in and of herself: a toxic agent who both materializes toxic history in herself, and feeds on her sole companions, performing the action of such toxic history. The refusal of the meat patty and the covering over of the creature in gas/smoke perform a variation on the erasure of black flesh by white supremacist history. However, when black flesh refuses itself, the stakes are entirely different from when white supremacist history refuses and unthinks it. Put simply, she puts her life in peril in performing the refusal, in speaking it in her own voice, in the flesh. This materialized dehiscent wound of black flesh puts white supremacist thought in peril because it has relied on her continued stasis, silence, and invisibility.

To No It: Pedagogics of Refusal and the Hunger Strike

As a register and document of willfully unthought history, black flesh is co-constitutive of the social and political fabric as much as she is its victim. To refuse and to flee the flesh that constitutes you is indeed a conundrum. Making visual art and expressions that focus on the "everyday mundane horrors that aren't acknowledged to be horrors," (Sharpe) yields texts that stage a disorienting self-refusal that "repeats the immiserating conditions or routinized scenarios confronted daily by black people" (Sharpe 3, Nyong'o 28). "The effect of that repetition," Nyong'o writes, "is to undermine the mechanics through which such domination is reproduced and dare us to imagine and act otherwise" (29). The visual and visceral reproduction of sanctioned violence disorients the ground of Thought (writ-white, writ-large), and a rigorous performativity of the daily lived experiences of racialized violence are a grotesque affront to the sanitized silencing and compartmentalization of such violence as benign, past, overcome.

Showing the trailer-excerpt of The End of Eating Everything in the classroom elicits reactions of fascination and discomfort, and at times recoil, with exclamations of "I don't know what I'm seeing! This is some kind of nightmare!" Such expressions reflect reactions that we might express when confronted with work that touches at a "black hole" of our knowledge base; of what we are trained to "understand." Black flesh in the two films above materializes the double violence of anti-blackness—first the violence, "it," and then its negation and disavowal: the "no" of "it" that is foundational to Western thought: a disorienting violence and degradation that is ant-blackness. The pain projected in these films encounters the horror of its negation as the negation rushes to tune it out in a convergence and collision of vectors, when viewers and students react with exclamations and recoil. The resonance of the negation in visceral response to seeing the effects of negation viscerally materialized, may forge a pedagogics of refusal that is based in recognition: to be shocked into asking questions about texts such as these and exploring the conundrums of a resonant refusal may encourage a "historical looking" that is cognizant of porosity (James 216).

The disorienting economy of flesh, autophagy, mortal peril, and stymied verbal communication that is palpable in both films might help to shape how we understand the hunger strike that Jonathan Butler, a graduate student of color from a notably wealthy family at the University of Missouri, recently undertook to protest inaction over racism on campus, and to call for the University president's resignation. The viscerally uncanny act of black flesh consuming itself on film is a more disturbing actuality when one is compelled to consider the medical reality of a hunger strike, where the striker's life is in peril because, at a certain stage in the process, the starving body begins to consume its own internal organs. In a publically shared statement, Butler writes,

A hunger strike specifically speaks to the nature of the beast that we're dealing with when we talk about systemic issues, because it deals with humanity. I think what I want people to come away with, if nothing else, (is) to understand [...] that I'm literally willing to give up my humanity to see some injustices stop.

Butler's response to a toxic environment of racism has been met with critique, condemnation, commendation and, ultimately, a powerful show of support from his community. The hunger strike reproduces the perilous and deadening effects of the quotidian horrors that constitute and perpetuate the "position of the unthought," and this is particularly pertinent in light of the university's marked silence on the issue of racism on campus. The embodied and intentionally literal, fleshy reproduction of suffering and deprivation compels us to look at and see a non-sanitary, non-overcome history of the present that needs to be acknowledged and thought, because and in spite of the visceral disorientation that such a view necessarily draws forth.

Works Cited

Anthony, Sebastian. "Stephen Hawking's new research: 'There are no black holes.'" ExtremeTech, 27 Jan. 2014. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

"archive, v." Oxford English Dictionary Online. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

Artnet. "Interview with Artist Wangechi Mutu." Online video. YouTube, 14 Nov. 2014. Web. 31 Dec. 2015. «https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ux0C_c08dto».

Baker, Houston A., Jr. Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

BCRW Videos. "Denise Ferreira da Silva - Hacking the Subject: Black Feminism, Refusal, and the Limits of Critique." Vimeo, 22 Oct. 2015. Web. 31 Dec. 2015. «https://vimeo.com/146790355».

Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaux: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Eidelson, Josh. "Exclusive: Inmates to strike in Alabama, declare prison is 'running a slave empire.'" Salon, 18 Apr. 2014. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

Finkel, Michael. "STAR EATER." National Geographic 03 2014: 89-103. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

Freealabama Fam. "FREE ALABAMA MOVEMENT: FAM—MEAT PATTIES." YouTube, 28 Dec. 2013. Web. 31 Dec. 2015. «https://youtu.be/EnzxwzJIE58».

Kovacs, Kasia. "UPDATE: MU student embarks on hunger strike, demands Wolfe's removal from office." The Columbia Missourian, 2 Nov. 2015. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

Hammonds, Evelynn. "Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality," Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 6.2-3 (1994): 126-145.

Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

—. Lose your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2007.

—. "Venus in Two Acts," Small Axe, 26 (2008): 1-14.

Hartman, Saidiya V. and Frank B. Wilderson, III. "The Position of the Unthought," Qui Parle 13.2 (2003): 183-201.

Hedges, Chris. "America's Slave Empire." truthdig, 21 Jun. 2015. Web. 31 Dec. 2015.

James, Jennifer C. "Looking," Feminist Studies, 42.1 (2015) Forum: Teaching about Ferguson: 211-237.

Keeling, Kara. The Witch's Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

MOCAtv. "Wangechi Mutu + Santigold—The End of eating Everything - Nasher Museum at Duke." YouTube, 21 Mar. 2013. Web. 31 Dec. 2015. «https://youtu.be/wMZSCfqOxVs».

Mutu, Wangechi. "Wangechi Mutu My Dirty Little Heaven." Online video of November 18, 2010 lecture. YouTube, 7 Jan. 2011. Web. 31 Dec. 2015. «https://youtu.be/SNBjxPM6JDM».

—. "The End of eating Everything," 2013. Courtesy of the Artist and Gladstone Gallery. Commissioned by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. © 2013 Wangechi Mutu and Wangechi Mutu Studio.

Moten, Fred. "Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)," The South Atlantic Quarterly, 112.4 (2013): 737-780.

Nash, Jennifer C. "Black Anality," GLQ, 20.4 (2014): 439-460.

Nyong'o, Tavia. "Between the Body and the Flesh: Sex and Gender in Black Performance Art," Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art. Houston: Contemporary Art Museum Houston, 2013. 26-29.

Parker, Annabelle. "'Let's just shut down': an interview with Spokesperson Ray of the Free Alabama Movement." San Francisco Bay View, 2 Dec. 2014. Web. 31 Dec 2015.

Puar, Jasbir. "Prognosis Time: Toward a Geopolitics of Affect, Debility, and Capacity." Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 19.2 (2009): 161-172.

Sexton, Jared. "The Social Life of Social Death," InTensions Journal, 5 (2011): 1-47.

Sharpe, Christina. Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Spillers, Hortense. "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book," Diacritics, 17.2 (1987): 64-81.

Stinson, Elizabeth. "Means of Detection: A Critical Archiving of Black Feminism and Punk Performance," Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 22.2-3 (2012): 275-311.

Warren, Calvin L. "Black Nihilism and the Politics of Hope," CR: The New Centennial Review, 15.1 (2015): 215-248.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Bioplotics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Wilderson, Frank B., III. Red, White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

—. "Gramsci's Black Marx: Whither the Slave in Civil Society?" Social Identities, 9.2 (2003): 225-240.

Williams-Forson, Psyche. Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Notes

- Here I am referring to the configurations of the thought human as afforded in enlightenment "thinking" (Warren).

- This is a reference to the verb form of archive, from the Oxford English Dictionary, which notably has it as follows: " trans. To place or store in an archive; in Computing, to transfer to a store containing infrequently used files, or to a lower level in the hierarchy of memories, esp. from disc to tape."

- Denise Ferreira da Silva recently noted this process in a talk at the Barnard Center for Research on Women and Gender.

- Saidiya V. Hartman writes about suffering flesh and the intensification of suffering with so-called liberation (1997); Alexander G. Weheliye's recent book theorizes flesh as a zone of potentiality and resistance (2014); Frank B. Wilderson, III writes of black flesh in the political economy as akin to the processed flesh of cattle: marked for death and accumulation, more than anything else (2003); Fred Moten meditates on black flesh as a site of this "fantasy in the hold" that he riffs from Wilderson's introduction to Red, White & Black: a way to dream of different futures while grounded in the realities of "the hold" of the slaveship and its persistent resonances (2013).

- To again quote Moten, blackness effects an "irreparable disturbance of ontology's time and space" (739).

- Houston A. Baker, Jr. (1984), Evelynn Hammonds (1994).

- As an informational National Geographic article from puts it, black holes "help determine the fabric of the universe" (2013).

- Thanks to Jennifer C. James for pointing me in the direction of this insight.

- Flesh reminds us that such terms as "optimism" and "pessimism" are beside the point. Flesh refuses allegiance to the Manichean designators of optimism and pessimism. As Moten and Sexton have both noted, the ethical rigor of pessimism is vital to optimist thought, just as Afro-pessimism is "not but nothing other than black optimism" (Sexton 37). As Moten puts it, "if pessimism allows us to discern that we are nothing, then optimism is the condition of possibility of the study of nothing as well as what derives from that study" (774).

- Science historian and feminist scholar Evelynn Hammonds suggests that different geometries of thought are necessary to articulate what it is like inside of a black hole (139). In a recent discussion of black nihilism, Calvin L. Warren suggests writing in a way that "refuses the geometry of thought" (214). The latest quantum theoretical research (the latest paper by Stephen Hawking in January 2014) on black holes shows that where it was previously thought that information maintains that contrary to previous theories, it is no longer the case that material absorbed into the black hole becomes irrevocably irretrievable: rearranged beyond recognition of its previous form. It emerges transformed, with a different grammar and geometry altogether (Hawking).

- More information here.

- Ray explains, "I knew that I had to document all of our grievances and produce proof for the public of why we were protesting. I was not going to allow [the Alabama Department of Corrections] to control the narrative in the media about our legitimate complaints" (Parker).

- Since the film is intended for gallery viewing, it is played on a repeated loop, and so the creature is also constantly reconstituted. While her flesh is a state of wound dehiscence, she herself dehisces as a follicle, only to reconstitute as dehiscent flesh, over and over again, as the film loops back to the beginning, repeating the scene of carnage and refusal without end.

- Mutu speaks about this in a talk at the University of Michigan, for instance.

- The creature performs a sniffing and smelling gesture when she comes on screen, modeling this approach perhaps.

- All images in this section are screenshots from the YouTube video.

- Or, more properly, lysis, per Moten's discussion of the term (from Fanon) in "Blackness and Nothingness" (757-775).

- Ray does close out the recording with by opening outward briefly form the meat patties as exemplary of the human rights violations and overcrowded conditions in the prisons, and asking for opportunities for education and rehabilitation, though his voice remains difficult to hear.

- In the sense that the visual grammar evokes the pornographic money shot, and also referencing Hortense Spillers's use of the word, and Alexander Weheliye's discussion of pornotroping as an eroticization of the violence in black flesh (Spillers 1987, Weheliye 2014).

- A semiotic shift that conflates and consummates the comparison that Wilderson evokes of cattle and slave-subjects as meat marked for "accumulation and death" (2013).

- The patty is in effect a dangerous predator: poisonous and diseased. At one point in the recording, Ray jokes to an off-screen co-inmate, "you eat one of these, you might not have five minutes to live."

- Images in this section are stills provided by Wangechi Mutu, excerpted from "The End of eating Everything", 2013. Courtesy of the Artist and Gladstone Gallery. Commissioned by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. (c) 2013 Wangechi Mutu and Wangechi Mutu Studio.

- The birds are her companions in fugitive existence, as the poem that follows the opening of the film states. The birds can also here be read as the inmates' flesh figured as black jailbirds. Thus, we have unfree black flesh consuming itself.

- This second line stages a skeptical dialogue, further undermining any potential determinacy or hopefulness. Further, this couplet is an internal dialogue speaking from the compromised "I"-subject of the poem's opening couplet. As a result, the second-person address is significantly absent as a category of the subject in the poem: there is only the compromised "I" followed by the much farther-removed, indeterminate, and object-like third-person subject "it," and then the even more indeterminate third-person hole-like article "who." In the slippage of the subject from "I" to "it/who" between the two couplets, the lack of the second person heightens a sense of isolation and illegibility. The "third person" is the case of the disfranchised subject, with no agentic political voice.

- "It" is also here the grammatically the dead object, the personless subject, the disfranchised subject.

- The ellipsis here is also the deformation of an orbit: The dehiscent speech-act of the register of unthought violence materializes the continuing orbit of an archive of violence and discourse around black flesh: continuing and returning and limning the dense core, its orbit deformed by the gravitational force of that which is not possible to think nor to fully erase.

- This occluded repetition is in large part the reason and the state of the increase in suffering that "emancipated flesh" experiences in Hartman's account, since it is a continuing suffering that is deeply denied, a state of "everyday mundane horrors" that Christina Sharpe's phrase "post-slavery" describes.

- Jared Sexton describes the condition of captivity as "a nervous system always in pursuit of the fugitive movement it cannot afford to lose and cannot live without, if it is to go in existing in and as a mode of capturing" (9-10).

- The occluded history between the lines materializes a haunting pursuit in the flesh, ineluctable because attached and constitutive. Notwithstanding the terrifying dystopic element, it is notable that where the first two lines are spoken in the first-person-singular "I" that is the grammar, paragon, and pillar of western thought and enlightenment humanism; the last word, "together," seems to speak to a different order and social grammar. This suggestive hope is yet again destabilized as the creature utters a scream that electrifies her whole shape, and abruptly begins to feed on the birds out of the sky.

- Where Melvin Ray's hands actively handle the meat patty in the previous video, here, the mass of flesh moves itself, with arms more as passive and decorative appendages.

- The olfactory immediacy is not one that is in fact available from the experience of watching the film, though the evocation of filth is a palpable one, and is notably absent from the closing scene.

- Mutu's fleshy creature's scream after the poem might itself parallel such a reaction, in and as an incredulous citation-reaction of horror and rage. Arguably, even farther, the creature herself is a congealed and dense scream, just as the film itself is a distorting filmic scream emerging from a white screen on a white wall in a gallery space, and just as the opened-up meat patties in the FAM video figure a revolt and a scream. Mutu's film is punctuated by a total of three screams, at regular intervals, from an increasingly removed perspective. The scream is thus a part of the creature's rhythm and motion, as a part of her recursive action as a moving creature.

- Does the disorientation and revulsion effect a learning? Is this a productive unlearning? Can it effect possible change? Perhaps, if the students become deeply enough affected. Alcorn and resistance to learning

- There are many articles online with this information; the source for this happens to be here.

Cite this Article

https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/029.e15