Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

‘How Much Truth Can a Spirit Endure?’ – A Nietzschean Perspective on the Possibility of Formulating Critique within the Context of Modern, Popular Music

Mathijs Peters

PDF

PDF

The way you get your own spirit through your own suffering. Self-chosen. Self-made. This boy’s done that. He’s created his own desperate ceremony… Just to ignite one flame of original ecstasy in the spiritless waste around him… He’s destroyed for it, horribly. He’s virtually been destroyed by it…. Well, let me tell you something. I envy it. – Richard Burton as Martin Dysart in the film Equus

Critique

There are different ways to criticize the society and culture in which the critic herself is embedded. In his 1987 Interpretation and Social Criticism, Michael Walzer focuses on this topic, driven by the following question: if the critic herself forms part of and is shaped by the same social and cultural context she aims to criticize, how does she create the distance necessary for developing a critical perspective on this same context? Walzer describes three different forms of social critique. What distinguishes these forms, in his view, are the ways in which they constitute this critical distance. Put differently: each form of critique is based on a different critical yardstick; a norm or value used by the critic to ‘measure’ the status quo by and criticize or affirm aspects of this status quo.

Walzer characterizes these three forms of critique as follows, referring to the three different paths they take towards the constitution of a critical yardstick: ‘the path of discovery, the path of invention, and the path of interpretation’. He argues that the first path can be religious in nature - the discovery of divine truths (the Ten Commandments, for example, can be used to criticize a social context in which these commandments are not implemented) - but also secular - the discovery of natural laws that function as objective truths (we can think of John Locke’s claim that property is a natural right, which implies that if this right is not uphold in a society, this society can be criticized). The second path consists of the invention of theories - political, moral, social - that provide us with norms and values that we can use to criticize the society in which we live (Walzer mentions John Rawls’ notion of justice and Jürgen Habermas’ understanding of communicative reason as examples). The third path that Walzer describes and which he himself embraces is the path of interpretation: instead of discovering or manufacturing norms or values to measure a society by, Walzer claims that that the social critic should interpret and reinterpret already existing social norms and values: ‘he [the critic] finds a warrant for critical engagement in the idealism, even if it is a hypocritical idealism, of the actually existing moral world’. If people in a society, for example, uphold a specific understanding of freedom, the social critic can interpret and reinterpret this understanding to criticize those processes in this society in which people are not free.

If the critic uses an already existing value to criticize certain aspects of a society, Walzer argues, she can be sure that this value is already experienced as normatively binding within this same society. The paths of discovery and invention, on the other hand, are less convincing, less flexible and therefore more dogmatic, in his view, since they introduce values into a society in which they are not necessarily experienced as normatively binding or as important: they do not form part yet of the social fabric. In his own words, they ‘are efforts at escape, in the hope of finding some external and universal standard with which to judge moral existence.’

In this paper, I am not interested in the details of Walzer’s analysis of critique. What I am interested in, however, is his claim that, to convincingly formulate critique, the critic needs a yardstick or norm, principles or values, that make it possible to constitute a distance between herself and that which she seeks to criticize. If not ‘objective’ or ‘universal’ in nature, Walzer suggests, this yardstick needs to be collectively shared within a social and cultural whole to successfully function as a critical yardstick.

In this paper, I aim to focus on a form of critique that affirms the idea that one has to constitute distance between oneself and that which one aims to criticize, but that offers a different method to constitute this distance. This form of critique revolves around a notion of ‘truth’, but is radically different from the first form of critique discussed above – religious truths revealed by a divine entity or natural truths discovered ‘in’ the world. Furthermore, I will argue that this alternative notion of truth is intrinsically tied to the individual body and mind of the particular critic, which makes it impossible to universalize, rationalize or conceptualize it, as critics like Habermas or Rawls do to provide their truths with a normatively binding force. Thirdly, I will show that it is based on an almost complete rejection of everything that exists, which makes it difficult to characterize it as Walzer’s ‘path of interpretation’.

I will exemplify this form of critique with help of several of Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas, and then argue that one of the realms in which the critic who propagates the notion of truth on which it is based can nowadays be found, is the realm of modern, popular music. This latter point will be made with help of an example: the posthumously released lyrics by Richard Edwards, guitarist of Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers.

Being One’s Truth

In Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is, Friedrich Nietzsche provides an overview of his life and his works, and presents everything he has done and everything that has happened to him as necessary steps in the formation of his philosophy. He does this against the background of his diagnosis of the death of God and the resulting nihilism, which he most famously illustrated with the parable of the madman:

Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the marketplace, and cried incessantly: “I seek God! I seek God!” […]

Whither is God?” he cried; “I will tell you. We have killed him you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? […] Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

[…] “I have come too early,” he said then: “my time is not yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, still wandering; it has not yet reached the ears of men. Lightning and thunder require time…

The idea that the madman speaks his prophetic truth ‘too early’ echoes through Ecce Homo as well, in which Nietzsche presents himself as a prophet whose radical and renewing ideas have yet to be fully understood: ‘My time has not yet come, some people are born posthumously.’

The main ideal expressed by Ecce Homo is embodied by the character of Zarathustra, the prophet that Nietzsche gave shape in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In a world in which the voice of reason has resulted in the death of God, in a wiping out of our moral and religious horizons and in a distancing from the sun, the philosopher can only move forward, he argues, and constitute his own values by creating his life like an artwork: by embracing his own fate – Amor Fati – and becoming his own sun. Only the weak need religious or moral systems, Nietzsche observes, since this enables them to hide behind the (Christian) idea that they are, by definition, sinful and powerless and cannot change their condition.

Nietzsche not only criticizes Christianity for being hostile towards the intellect, he also rejects its negative understanding of the body. Instead of praising the strength and beauty of the corporeal dimension of existence, Christianity portrays the flesh as ‘weak’ and sinful, and life as revolving solely around matters of the ‘soul’. Besides Zarathustra, Nietzsche refers in Ecce Homo to Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, fertility and ritual madness, as symbolizing that which Christianity tried to repress and overcome, signing the book with the line ‘Dionysus against the crucified’.

The ‘truth’ on which Nietzsche bases his critical diagnosis of humanity, therefore not only represents insight into the nature of life and of the universe, but also a stance that makes it possible to create one’s own values and throw oneself into the world. He therefore moves away as well from the, in his view, passionless, bodiless and powerless truths sought after by theoretical science and most of the philosophers that went before him: ‘To speak truth and shoot well with bow and arrow, that is the Persian virtue. – Am I understood? … The self-overcoming of the moralist into his opposite – into me – that is precisely what the name of Zarathustra means in my mouth.’ The arts play an important role in this self-overcoming, and Nietzsche frequently contrasts the passionate, creative and Dionysian nature of certain artists with the dry and disembodied realm of theory and religion.

In Ecce Homo, the idea that one truly has to embrace one’s fate returns in Nietzsche’s claim that even that which happened to him and over which he had no control (his father’s early death, his worsening eyesight and his migraines, for example) should be interpreted as necessary for the formulation of the truth that he, as a specific individual, came to manifest. He describes his 1881 work Daybreak, for example, as made possible by a heavy migraine attack: ‘In the midst of the torments of an uninterrupted three day brain-pain accompanied by troublesome vomiting of phlegm – I possessed a dialectical clarity par excellence and thought very cold-bloodedly through things for which in healthier circumstances I am not enough of a social climber, not cunning enough, not cold enough.’ Even the weakness of the body, its vulnerability to suffering and pain, in other words, can be understood as signs of power and strength, in Nietzsche’s view, since they provide the author with a ‘coldness’ and distance required to criticize humanity.

Nietzsche does, in other words, affirm Walzer’s idea that the critic requires distance from that which she seeks to criticize: not only does he use exaggeration and a violent style to create as much distance between himself and the world, he also presents his ideas as revolving around a prophetic truth that has yet to be understood and therefore does not arise from within the society in which he lives. This last aspect differentiates his critique from Walzer’s: whereas Walzer argues that this distance can be constituted by interpreting and reinterpreting already existing values and norms, Nietzsche seeks to constitute a ‘re-evaluation of all values’ by turning himself completely against the world – this world, after all, has been drained of values and norms and there is nothing the critic can cling to anymore, he argues; we have wiped away ‘the entire horizon.’

Furthermore, whereas Walzer’s critic focuses on principles and norms to measure the world by and appeal to as many people as possible within a social context, Nietzsche steps away from this need to universalize or conceptualize and makes his critique as particular as possible: he turns his specific mind and his specific body into critical yardsticks, even using the illnesses and suffering that his body and mind have been through as instruments to create a distance between himself and that which he seeks to criticize – humanity as a whole. An implication of this form of critique, in other words, is that if the critic had lived a different life, had not suffered through illnesses or traumatic experiences, the nature of her critique would be different.

Three Sides of Truthfulness

This means as well that the ‘truth’ around which Nietzsche’s critique revolves is particular in nature and therefore different from the notions of truth that function as critical yardsticks on Walzer’s ‘paths’: truth as ‘delivered by God’, as ‘discovered in nature’ or as discovered within the fabric of a society. Again: not only is it born in a specific historical and cultural context, it is also tied to Nietzsche himself as an individual subject and an individual body. This raises the question if it is possible to generate this kind of critique anew? Being an embodiment of this kind of critique, has it not died with Nietzsche? And should it therefore not be understood as a flash of lightning that is witnessed only once in the history of humanity, similar to the manner in which Nietzsche himself presented his ideas?

Before attempting to formulate an answer to this question, I want to explore the specific nature of this form of critique in more detail. My argument is as follows: defending the nobility and purity of speaking and being a truth that enlightens the world and at the same time destroys everything believed thus far – of becoming one’s own sun in a sunless world – is a three-sided endeavour, of which each side revolves around a different theme, each theme being intrinsically tied to the critic herself: vulnerability, militancy and madness.

Nietzsche’s works are permeated with the second theme – militancy – as he claims over and over that he is a destroyer – ‘I am not a man, I am dynamite’ – and that his ‘truth is frightful: for thus far the lie has been called the truth’. This superiority is embodied by his defence of the Übermensch or overman, who transcends and overcomes humanity by constituting himself independently, without the need for a religious or moral system: ‘Truly, mankind is a polluted stream. One has to be a sea to take in a polluted stream without becoming unclean. Behold, I teach you the overman: he is this sea, in him your great contempt can go under.’

This militant stance is surrounded, as it were, by two perspectives that expose its more vulnerable sides. After all, Nietzsche embeds his defence of the idea that he is his own truth in a post-religious landscape: the demand to be truthful, to become like Zarathustra and Dionysus, is driven by the need to become who one is in a world in which all moral and religious values have been exposed as false and have crumbled down. His defence of the Übermensch, however, implies that human beings themselves are too weak, needy and dependent to truly become who they are. The observations made in Ecce Homo, in other words, suggest that human beings are destined to suffer from another truth: that they are alone in the universe. As Albert Camus, strongly influenced by Nietzsche, famously put this idea into words in his essay on meaning and suicide: ‘In a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lights, man feels an alien, a stranger. His exile is without remedy since he is deprived of the memory of a lost home or the hope of a promised land.’

Put differently: if one arrives at the truth that the world is meaningless, one longs for a religious truth embodied by a god or a beyond. But as soon as one realizes that such a truth is empty as well – that God does not exist since He is a truth made up by human beings – one has to accept the nihilistic truth again that the universe is empty. The only way to escape this circle of empty and disempowering truths, Nietzsche argues, is to become one’s own truth. Whereas Jesus said: ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me’, Nietzsche therefore proclaimed in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: ‘This is my way; where is yours?’, emphasizing the power of individual creativity and independence. Again, this implies that Walzer’s ideas about developing critique are not applicable to Nietzsche’s worldview: we cannot discover divine or natural truths in the world, nor can we cling to truths already existing in a society. Furthermore, we cannot invent philosophical theories that constitute universally binding principles and concepts like ‘justice’ or ‘fairness’ or ‘freedom’, since the faculty of reason brings us nothing but empty and dead concepts. The only thing we can do is create particular truths and turn ourselves as particular individuals into critical yardsticks.

The third perspective on the notion of truth that Nietzsche develops is constantly present in the background of his works, especially his later writings: madness. He wrote Ecce Homo in 1888, but it was published posthumously in 1908. It is the last original book he produced before slipping into a state of insanity, beginning with a nervous breakdown during which he allegedly broke into tears and embraced a horse that was beaten on a square in Turin. Nietzsche’s descent into madness can be read through the lines of Ecce Homo. His hyperbolic outbursts, his need to overpower his opponents, his declarations of superiority, his longing for truth, his rivalry with Jesus as a weak prophet, his almost manic attempt to burst through the pages and undermine and destroy the nature of humanity, expose the vulnerability of a mind that is on the brink of collapse.

Before he completely slipped into insanity, the German philosopher wrote letters to friends and to royal figures, calling for the death of the pope and for military leaders to invade Germany, signing these letters either as ‘the crucified’ or as ‘Dionysus’. Several medical theories have been developed about his illness; a brain tumour, syphilis, manic depression, progressive paralysis, bipolar disorder or frontotemporal dementia. Predicting his own fate, Nietzsche himself had already observed in Daybreak: ‘All superior men who were irresistibly drawn to throw off the yoke of any kind of morality and to frame new laws had, if they were not actually mad, no alternative but to make themselves or pretend to be mad,’ and had prophetically asked in Ecce Homo: ‘How much truth can a spirit endure, how much can it dare?’

In ‘Nietzsche’s Madness’, the French philosopher Georges Bataille develops this idea further. Instead of analysing Nietzsche’s medical condition, he focuses on his ideas, arguing that Nietzsche’s understanding of truth is intrinsically linked to the demise of his psyche. He therewith develops a strong argument for the claim that the form of critique developed by Nietzsche requires a complete entwinement of body and mind, of theory and person:

He who has once understood that in madness alone lies man’s completion, is thus led to make a clear choice not between madness and reason, but between the lie of ‘a nightmare that justifies snores’, and the will to self-mastery and victory. Once he has discovered the brilliance and agonies of the summit, he finds no betrayal more hateful than the simulated delirium of art. For if he must truly become the victim of his own laws, if the accomplishment of his destiny truly requires his destruction, if, therefore, death of madness has for him the aura of celebration, then his very love of life and destiny requires him to commit within himself that crime of authority that he will expiate. This is the demand of the fate to which he is bound by a feeling of extreme chance.

If one seeks to embody a truth that transcends humanity, Bataille observes, one eventually undermines one’s actual psyche: thought, body and existence of the critic, in other words, are one, and if one’s ideas are radical, one’s embodied existence changes radically - Nietzsche claimed he was dynamite, and the only way to become his destiny was to explode. Bataille emphasizes the religious nature of this idea by referring to the notion of ‘incarnation’ and comparing Nietzsche, in this sense, to Christ:

Beyond endless, mutual verbal destruction, what else remains but a silence driving one to madness in laughter and in sweat? But if the generality of men – or if, more simply, their entire existence – were to be INCARNATED in a single being – as solitary and abandoned, of course, as the generality – the head of that INCARNATION would be the site of inappeasable conflict, a violence such that sooner or later it would shatter. [..] He would look upon God only to kill him in that same instant, becoming God himself, but only to leap immediately into nothingness. […] This leads to the inevitable acknowledgement that “man incarnate” must also go mad.

Nietzsche, Bataille observes, eventually came to embody his own truth and turned into the prophetic madman he had described earlier in his life.

Bataille herewith emphasizes the above-mentioned particularity of this form of critique and the way in which it is intrinsically tied to a specific mind and body. As a critic who seeks to go against everything around and in himself, as a critic who uses his own bodily and mental illnesses as ways to constitute distance between himself and the world, and as a critic who seeks to become the embodiment of his radical critique, Nietzsche eventually had to overcome himself and step over the edge of sanity, Bataille observes.

Popular Music

As briefly mentioned above, this combination of characteristics is so specific and particular that it seems impossible to claim that this form of critique can be formulated again. In the following, however, I want to argue that it is possible. One of the requirements for formulating this kind of critique is becoming an embodiment of one’s ideas, turning one’s mind and body into a passionate manifestation of one’s position as a critical outsider, shining a prophetic and blinding light on the world. Nietzsche’s affinity with the realm of the arts suggests that specific artists, who entwined their suffering and their mental struggles with their creations and with their existence, could be understood as examples. Painters like Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso or Mark Rothko come to mind, as well as a poet like Arthur Rimbaud or an author like Yukio Mishima, to which I will return below.

In the following, however, I want to focus on modern, popular music. Within this realm, the musician’s body is intrinsically tied to his or her performative style: the musician presents herself in a specific way on stage, poses for pictures that accompany releases, posters and interviews, and can therefore make use of clothes, body art, poses and settings to present herself as a physical manifestation of her critical ideas. Given Nietzsche’s emphasis on originality, individuality and uniqueness, artists within this realm can use different ways of turning themselves into embodied manifestations of their ideas – they do not, in other words, completely have to mirror Nietzsche’s style. For example, the artists can experiment with different personas, each embodying a specific perspective, each creating a specific critical distance between self and the world. David Bowie’s personas come to mind, such as Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, The Thin White Duke and the literal ‘alien’ in The Man Who Fell to Earth. Another artist one could think of is Bob Dylan, who constantly reinvents himself (as a folk singer, a born again Christian, a performer of Sinatra classics) and famously refuses to be clear about who or what he is and why he does what he does or sings what he sings. This makes Dylan only graspable during specific embodied performances and at specific moments; there is not one essence of Dylan which unifies all of these performances. Yet another example is Beyoncé, whose 2016 ‘visual album’ Lemonade forms a critique on race and gender relations through an entwinement of the artist’s voice, body, dance moves, lyrics and performance.

But there are more possibilities: for example, whereas Bowie ‘himself’, understood as a specific individual and body, disappears behind the personas he plays, other artists use their specific bodies as part of their art form, coming closer to Nietzsche in this respect. We can think of body art, which turns one’s body into the bearer of a specific and unchangeable sign or symbol, but also of Iggy Pop and Sid Vicious, who mutilated themselves on stage and thereby made their bodies into aspects of their performances.

The example on which I want to focus in the following, however, is a less known musical figure: Richard Edwards, the guitarist and lyricist of Welsh alternative rock band Manic Street Preachers who mysteriously disappeared in 1995 and suffered from substance abuse and mental illness. What makes Edwards fascinating as an example of the Nietzschean form of critique discussed above, is that he often reflected intellectually – in interviews and lyrics – on his existence and status as a musician, and frequently did this by referring to writers, musicians, painters and philosophers, among whom was Nietzsche.

But there is another reason why I want to discuss Edwards: the above-mentioned examples of Bowie, Dylan and Beyoncé do not share the destructive and self-destructive aspects of Nietzsche’s truth. I have already mentioned that this is not necessary: I have used Bataille’s analysis of Nietzsche’s madness mainly to show that his philosophy and his actual existence as a particular person were intrinsically connected. This means that the form of critique that is formulated in Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo does not necessarily require the critic to become mad, only that existence, embodiment, thought and reflection should be bundled together and presented as one embodied manifestation of a critical force. However, I will show that, without being mere copies of Nietzsche’s ideas, the three above-described sides of Nietzsche’s notion of critical truth do return in Edwards’ life and lyrics and that this makes him into a very helpful and fruitful example to flesh out the ways in which the form of critique based on Ecce Homo can be applied to the realm of modern, popular music.

Manic Street Preachers

Before developing my argument, I will briefly provide background information on Edwards and on the band in which he played. Manic Street Preachers were formed in 1986 by James Dean Bradfield (vocals and guitar), Nicky Wire (bass), Sean Moore (drums) and Richard Edwards (guitar) in Blackwood, Wales. The band gained a cult following with their first three albums: Generation Terrorists (1992), Gold Against the Soul (1993) and The Holy Bible (1994). Having MA’s in politics and political history, Wire and Edwards became the main lyricists of the band. They positioned themselves in intellectual movements like Situationism and Marxism, but also made their releases into collages of references to philosophers and writers, to popular cultural products and to contemporary political events and figures, blurring the lines between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture and between political action and academic theory. The band accompanied their lyrics with quotes from authors, poets, political figures and musicians like Jean-Paul Sartre, Karl Marx, Malcolm X, Chuck D, the Futurists and Raoul Vaneigem, which they printed in booklets, used in the lyrics of their songs and spray-painted on their clothes. Together with their extravagant clothes, the wearing of make-up, and an over-the-top stage presence that often resulted in a destruction of their equipment, this forms an example of the ways in which musicians can present themselves as manifestations of ideas. See for an example of the ways in which Manic Street Preachers presented themselves in the beginning of their career, including clothes, spray-painted slogans and feminine looks, the following video-clip of their 1992 single ‘Slash ‘N’ Burn:

For the release of their third album, the band changed these looks to a more military and aggressive style.

Many of the intellectual references used by the band can be placed within the context of the discussion above, especially the aspect of religion. The song ‘Crucifix Kiss’ on their first album, for example, which forms a violent attack on Christianity’s attempt to keep people weak and favour the eternal instead of the present, was accompanied by the following quote from Nietzsche’s Human, All Too Human: ‘It was Christianity which first painted the devil on the world’s wall; It was Christianity which first brought sin into the world. Belief in the cure which it offered has now been shaken to its deepest roots; but belief in the sickness which it taught and propagated continues to exist’. During this time, Edwards also often wore a large crucifix, as depicted on the cover of Generation Terrorists. In an early interview, he stated that he wore it because he wanted to ‘dehumanize Christ’ and turn him, as a Warholian icon, into a Coca-Cola can, embedding both religion and popular music in the spectacle of consumption culture.

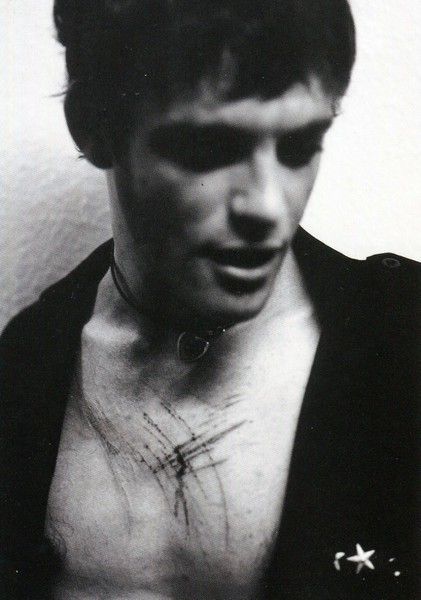

It was with their third album – The Holy Bible – that the band truly developed a voice of its own. More than on previous albums, the songs on this nihilistic and bleak album were influenced by the state of mind of Edwards, who wrote most of its lyrics, suffered from anorexia, depression and alcohol abuse, and cut and mutilated himself, sometimes even on stage, posing for pictures with his self-inflicted wounds and making them into an aspect of their presentation as a band (see Figure 1) – I will return to this aspect below. Not only do the lyrics on The Holy Bible contain descriptions of these problems from an almost analytical point of view that never becomes sentimental, they also contain reflections on the history of Europe, death camps, the bombing of Hiroshima and the emptiness of celebrity life. Edwards indeed explained the title of this album as follows: “The way religions choose to speak their truth to the public has always been to beat them down . . . I think that if a Holy Bible is true, it should be about the way the world is and that’s what I think my lyrics are about.” This statement comes from the following interview (his last TV interview), in which Edwards touches on many of the ideas discussed in this paper and reflects on the band’s first three albums as well:

The ability to reflect on himself and to explore his feelings from a distance did not defuse the hold that they had on Edwards, however. This became clear after the release of The Holy Bible, when his condition worsened. Edwards was committed in The Priory Hospital, a mental health institution in London. After his release and a tour, he gave his last interview on January 23. The pictures made for the interview show a very thin man with a shaved head and hollow eyes. In February 1995, Edwards disappeared, just before the band was to embark on an American tour. He was 27 years old. His car was discovered next to the Severn Bridge, a renowned suicide location in Wales, but his body has never been found. In his hotel room, he left a gift-wrapped box, containing books, literary quotes, and the films Equus and Naked. On 23 November 2008, he was officially declared ‘presumed dead’.

After his disappearance, the band decided to continue as Manic Street Preachers and released the commercially accessible album with the telling title Everything Must Go, spawning four highly successful singles. Speaking about the possibility of Edwards returning and becoming part of the band again, Wire observed: ‘Unless he’s had a miracle cure and become a Nietzschean strongman, I can’t imagine him wanting to go through all that again.’

The Vulnerability of a Longing for Truth

Above, I have argued that the form of critique developed by Nietzsche consists of three sides: vulnerability, militancy, madness. In the following, I will argue that each of these sides is represented by a different era in Edwards’ posthumously published lyrics. I aim to focus on his posthumously published lyrics, since these lyrics were released in three phases and each phase illustrates one of these three sides of truthfulness. Furthermore, whereas Edwards’ earlier released lyrics contain critique on society and tragic analyses of the human condition, it is in several of his posthumously published lyrics that he comes the closest to formulating religious themes and to notions of truth that are driven by a similar spirit as Nietzsche’s analyses. Again, this makes Edwards into a fruitful and helpful example to show how Nietzsche’s critical notion of truth can be used to interpret phenomena within the realm of modern, popular music.

The first of the three stages I want to discuss is formed by the 1996 album Everything Must Go. Of the twelve songs on the album, five contain lyrics written by Edwards, two of which were composed together with Wire. One of these songs - ‘Elvis Impersonator: Blackpool Pier’ - addresses the influence of American consumption culture on the UK, using the image of Elvis impersonators at the beach resort of Blackpool, Lancashire, as an allegory. Another one – ‘Kevin Carter’ – focuses on the South-African photographer of the same name, whose pictures of political violence and human catastrophes won him a Pulitzer Price, but who committed suicide in 1994. A third song - ‘Small Black Flowers that Grow in the Sky’- forms an intimate exploration of the suffering of animals hold in captivity.

In the following, however, I want to focus on the two other songs for which Edwards wrote lyrics and argue that they reflect the above-described first side of Nietzsche’s notion of truth – vulnerability. Furthermore, I will show that this side – revolving around the experience of an empty universe – forms a stepping stone towards the second side: the aggressive declaration of oneself as a god. The song on which I want to focus is ‘The Girl Who Wanted to be God’, which forms an example of one of the many authors to which Edwards referred in his lyrics. These references could be understood as driven by the attempt to put flesh on the bones of the ideas that Edwards wanted to embody. Furthermore, he herewith embedded himself in a rhizomatic network of links to songs, cultural and political figures to which he himself gave his own twist. These references partly affirm Walzer’s point that one needs to cling to already existing social phenomena to be able to formulate critique. However, whereas Walzer refers to norms or values in this context, I will show that in Edwards’ case these references form illustrations of the critical existence, of a Nietzschean truth that Edwards aimed to embody.

‘The Girl Who Wanted to Be God’ is partly about the American writer and poet Sylvia Plath, whose poems, literature and biography formed one of Edwards’ main influences. Plath was clinically depressed during most of her life and committed suicide at the age of 30. The song’s lyrics contain implicit references to many of her poems, consisting of words that Plath frequently used: dawn, silence, heaven, truth, lies, blind, eyes, and refer to a girl who told the truth but then lied. The song’s title is taken from the following passage, which the 17-year-old Plath wrote in her diary: ‘I want, I think, to be omniscient… I think I would like to call myself “The girl who wanted to be God.” Yet if I were not in this body, where would I be? … But, oh, I cry out against it. I am I – I am powerful, but to what extent? I am I.’

The passage in Plath’s diary embodies the idea, described above within the context of the first side of Nietzschean truthfulness, that one can get stuck between two equally dissatisfying truths: the truth of the meaninglessness of everyday life and of the flawed nature of one’s own body, and the truth of an idealized, divine and godlike image of oneself and the world that turns out to be meaningless as well. In the first chapter of the 1989 biography ‘Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath’, entitled ‘The Girl Who Wanted to Be God (1932-1949’), Stevenson argues that the above-cited passage from Plath’s diary presents ‘the hapless dualism of the Romantics’: ‘Was she wrong … to idealize herself even when the merciless mirror showed her the ordinary truth?’ On the one hand, Plath was who she was (‘I am I’). On the other hand, she aspired to be an ideal version of herself, an omniscient, pure, godlike version that was not bound to a specific body, or at least be close to one. In the booklet of their first album, Manic Street Preachers cited a line taken from the following entry in Plath’s journals, in which she reflects on her suicidal feelings and illustrates the first aspect of Nietzsche’s truthfulness as well: ‘I need a father. I need a mother. I need some older, wiser being to cry to. I talk to God, but the sky is empty, and Orion walks by and doesn’t speak’. As discussed above, Camus described a similar experience as ‘a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lies’, and in a poem expressing grief over her miscarriage, Plath wrote in a similar vein: ‘The round sky goes on minding its own business’.

This theme plays a guiding role as well in another song on Everything Must Go, ‘Removables’, for which lyrics written by Edwards were used. These lyrics mention a ‘bronze moth’ that ‘dies easily’. This phrase refers to the poem ‘Lament for the moths’ by the American poet and playwright Tennessee Williams, which opens as follows:

A plague has stricken the moths, the moths are dying,

their bodies are flakes of bronze on the carpet lying.

Enemies of the delicate everywhere

have breathed a pestilent mist into the air.

In Williams’ poem, moths can be understood as referring to the quiet and sensitive people who are ‘crushed’ and threatened by the violent, outside world – the ‘enemies of the delicate’. Williams’ poem ends with a stanza in which a higher, godlike being is asked to return the moths – the desired ‘delicate’ – to a bleak world that is haunted by ‘mammoth figures’. The lyrics to ‘Removables’ cynically describe human beings, in line of Williams’ moths, as ‘removables’, emphasizing the trivial and meaningless nature of human existence. The song also contains religious imagery, referring to a killed god and to guilt about ‘making holes’, expressing feelings of frustration with the inability to reach a pure, truthful existence and of being drawn into, even corrupted by, the world of ‘removables’.

The lyrics written by Edwards and used for songs on Everything Must Go express a longing for an indestructible, eternal or divine truth that, the author realizes, can never be found in the ‘removable’ real world that forces one to lie, as the girl in the lyrics to ‘The Girl Who Wanted To Be God’. This made him identify with Sylvia Plath and Williams’ moths, as well as with zoo animals and the troubled photographer Kevin Carter. These lyrics can therefore be interpreted as illustrating that which I have described as the first aspect of the form of critique embodied by Nietzsche’s posthumously released autobiography: human vulnerability and a concern with an empty universe in which one longs for a higher authority, for a sense of meaning that is not there.

Truth as a Militant Ideal

This emphasis on the vulnerability of longing for truth in a false and meaningless world, I have argued above, results within Nietzsche’s thought in a violent defence of oneself as a god and a turn against humanity; in the destructive attempt to declare oneself to be superior – to be a sun in a sunless world – and therewith destroy everything believed thus far. A similar transformation takes place between Everything Must Go and the second stage of truthfulness I want to describe within the context of Edwards’ posthumously released lyrics: the song ‘Judge Yr’self’. This song was initially written for the soundtrack of the 1995 movie adaptation of the comic book Judge Dredd. Indeed, its lyrics resonate with the themes of the comic book series ‘2000 AD’, in which the militant and ruthless character of Judge Dredd functions as police, judge, jury and executioner in a totalitarian and dystopian future. A demo was recorded in January 1995 with Edwards, but was never used. The song resurfaced on the 2003 compilation album Lipstick Traces (A Secret History of Manic Street Preachers), and was released with the following video-clip, consisting of old video fragments of the band:

The song, which is aggressive and metallic in nature, reintroduces Nietzsche, whose philosophy – and specifically the militant aspects of his thought discussed above – formed its main inspiration. In these lyrics, the phrase ‘Dionysus against the crucified’ returns twice; the last line of Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo. Furthermore, the beginning of the song’s video-clip, embedded above, shows the following quote by Nietzsche, typed by Edwards on a typewriter: ‘The devotion of the greatest is to encounter risk and play dice for death’. The line is taken from a passage in Thus Spoke Zarathustra called ‘On Self-Overcoming’, which Nietzsche concludes with the violent observation that ‘all truths that are kept silent become poisonous. And may everything be broken that cannot brook our truths!’ Nietzsche further emphasizes this destructive aspect of truthfulness in Ecce Homo as follows, providing it with a political tone:

I am necessarily also the man of disaster. For when truth enters into battle with the lies of millennia, we shall have convulsions, a spasm of earthquakes, a displacing of mountain and valley the like of which has never been dreamed. The concept of politics will then be completely taken up with spiritual warfare, all the power structures of the old society will be blown sky high – they all rest on lies: there will be wars like never before on earth.

Nietzsche’s aggressive defence of truthfulness as an entwinement of creation and destruction, returns in the lyrics to ‘Judge Yr’self’, which proclaim that the ‘brightest sun’ is formed by the ‘purest gun’, and, like a violent sermon, tell the listener to ‘find’, ‘face’, ‘speak’ and ‘be’ his or her ‘truth’, and to ‘heal’, ‘hurt’ and ‘judge’ his- or herself. During this phase, Edwards himself frequently reflected on the militant nature of his lyrics, emphasizing the particular and Nietzschean nature of his ideas: ‘Some of my beliefs could be construed as quite fundamentalist, Islamic almost. But it’s not. It’s quite alien to that. It’s much more individual.’

As with the side of vulnerability discussed above, Edwards put flesh on the bones of his ideas about the militant and aggressive character of himself as an embodiment of his own truth, by referring to several cultural influences, of which I want to briefly focus on the Japanese author, playwright, essayist and filmmaker Yukio Mishima and the character of Colonel Kurtz, both in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 epic war film Apocalypse Now and Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness.

Mishima formed the inspiration behind the cover of Manic Street Preacher’s second album – Gold Against the Soul – which shows a face covered with roses, a reference to Bareki (‘Ordeal by Roses’), Eikoh Hosoe’s collection of photographs of Mishima. Furthermore, Edwards frequently expressed admiration for the Japanese author, whose life could interpreted as an example of the second side of the Nietzschean entwinement of art, body and particular existence. Like Nietzsche, Mishima defended an entwinement of body and mind and strongly resisted the (Christian) idea that the mind is somehow higher or purer than the body. At the same time, he described the body in his autobiographical essay as a paradox – ‘a terrible paradox of existence’ – that, since it is vulnerable to decay and death, lives a life of its own that results in the annihilation of that same existence. Mishima practiced the art of body-building to fight his body’s vulnerability: ‘the body is doomed to decay.... I for one do not, will not, accept such a doom. This means that I do not accept the course of Nature.’ In the following interview, Mishima reflects on these issues:

Whereas Nietzsche explicitly expressed the idea that he needed to be alone and did not want to become part of a group – ‘to suffer from solitude is an objection – I have always suffered from the “multitude”…’ – Mishima translated his emphasis on the strength and purity of body and mind into a political ideology of a nationalist and fascist nature, celebrating traditional Japanese values of honour, strength and purity. He formed a militia called the Tatenokai (‘Shield Society’) and attempted to overthrow the government of Japan by invading the headquarters of the Japanese self-defence forces. After the coup failed, he committed seppuku: he ritually disembowelled himself, after which he was decapitated by an assistant.

By referring to Mishima, Edwards not only illustrated the aggressive nature of this second aspect of ‘truthfulness’, but also emphasized the importance of embodiment for this kind of critique. As discussed above, Nietzsche used his bodily suffering and his sickness to constitute a critical distance between himself and humanity. He thereby turned his bodily weakness into a sense of strength, itself an illustration of ways to become one’s own truth in a truth-less universe. Mishima emphasized the corporeal dimension of his militant stance through his body-building and through his fascination with self-inflicted pain, culminating in the act of seppuku. As mentioned above as well, Edwards suffered from anorexia and frequently mutilated himself, made these mutilations into a part of his art and furthermore presented his anorexia and his tendency to harm himself, in line of Mishima’s ideas, as an illustration of complete control over body and mind and therewith as an example of his Nietzschean idea of truth. He observed in his last British interview: ‘There’s a certain kind of beauty in taking complete control of every aspect of your life. Purifying or hurting your body to achieve a balance in your mind is tremendously disciplined,’ and expressed admiration for the IRA martyr Bobby Sands, who died on hunger strike in prison in 1981: ‘I thought he was a better statement than anything else that was going on at the time, because it was against himself.’ Figure 1 shows an example of the way in which Edwards aestheticized his auto-mutilation:

Edwards also made sure that his auto-mutilation could not be reduced to a mental illness, by embedding it in references to authors and cultural figures and thereby turning it into a deliberate statement that formed part of the truth he wanted to express, not unlike Bataille’s approach to Nietzsche’s madness. In late 1994, for example, he wore a boiler suit during a photo-shoot in the catacombs of Paris with the following lines from different parts of Arthur Rimbaud’s 1873 A Season in Hell written on the back: ‘Once, I remember well, my life was a feast where all hearts opened and all wines flowed. Alas the gospel has gone by! Suppose damnation were eternal! Then a man who would mutilate himself is well damned, isn’t he?’

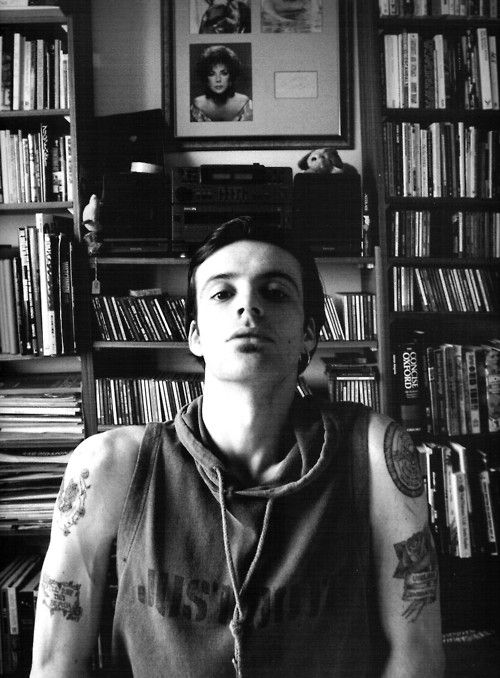

As a modern, popular musician, another way of making one’s own body into a part of one’s particular and individual form of critique is through tattoos. Early in his life, Edwards had the phrase ‘Useless Generation’ tattooed on his arm, making himself into an embodiment of his critique on the, in his view, nihilistic generation of which he formed part. Not long before his disappearance, he had the line “I’ll surf this beach” tattooed on his arm, referring to the second cultural example I want to discuss: the film Apocalypse Now. The line refers to a scene in which the character of Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore (played by Robert Duvall) expresses his desire to surf at a beach in a warzone in Vietnam. Based on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse Now famously tells the story of Captain Benjamin L. Willard, who is sent on a secret mission to find and assassinate Colonel Walter E. Kurtz (played by Marlon Brando) during the Vietnam War. Before his disappearance, Edwards decorated the band’s dressing rooms as camouflaged war zones, and wore a camera of the same model as the one used by a photographer in Apocalypse Now (played by Dennis Hopper), who has become a mad disciple to Colonel Kurtz. Again, he herewith made himself and his performative persona as an artist into an embodiment of the critical truth he wanted to be.

The militant side of becoming one’s own truth is emphasized in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in which Marlow (on whom Apocalypse Now’s Willard is based) describes Kurtz as follows, referring to him famously whispering the words ‘The horror! The horror’ when he is dying:

This is the reason why I affirm that Kurtz was a remarkable man. He had something to say. He said it. Since I had peeped over the edge myself, I understand better the meaning of his stare, that could not see the flame of the candle, but was wide enough to embrace the whole universe, piercing enough to penetrate all the hearts that beat in the darkness. He had summed up – he had judged. ‘The horror!’ He was a remarkable man. After all, this was the expression of some sort of belief; it had candour, it had conviction, it had a vibrating note of revolt in its whisper, it had the appalling face of a glimpsed truth – the strange commingling of desire and hate.

As in the lyrics to ‘Judge Yr’self’, the notions of truth – this time a glimpsed truth with an ‘appalling face’, a combination of hate and desire – and of ‘judging’ return. Like Nietzsche in Ecce Homo, Kurtz represents the psyche of a man who, according to himself, sees through the falseness of the world, who destroys the simplicity of a morality based on a duality of good and evil, and constitutes his own truth by way of a vision that is both desire and hate, both creation and destruction.

Based on these analyses, the second stage in which Edwards lyrics were released – embodied by the song ‘Judge Yr’self’ – can be interpreted as revolving around the militant and destructive nature of Nietzsche’s defence of truthfulness. Following the expression of vulnerability and hopelessness that characterizes the first stage, Edwards now writes about the desire to make himself into a god in a godless universe and to be the only judge of his own existence. With help of references to Nietzsche, Mishima and Kurtz, furthermore, he emphasizes the radical, destructive and personal character of this second side of critique, showing how deeply it is tied to the actual body of the critic, its specific characteristics, its ability to undergo suffering – even suffering that is self-inflicted – and its possibility of functioning like a canvas for body art.

Truthfulness as Self-Destruction

Above, I have argued, with the help of Bataille, that the critique Nietzsche develops almost necessarily results in madness and in a corrosion of the stability and solidity of the mind. A destruction directed outwards tends to evolve, within this context, towards a destruction directed inwards. This idea is illustrated again by two of the examples Edwards used to strengthen his ideas: Mishima eventually committed suicide in a way that forms a continuation of his ideas about self-control, purity and militancy. Kurtz, on the other hand, attempted to overcome himself and ended up in a state of madness. In Heart of Darkness, Marlow describes this theme as follows:

[Kurtz] had made that last stride, he had stepped over the edge, while I had been permitted to draw back my hesitating foot. And perhaps in this is the whole difference; perhaps all the wisdom, and all truth, and all sincerity, are just compressed into that inappreciable moment of time in which we step over the threshold of the invisible.

Kurtz stepped over the threshold and looked into the abyss. And as Nietzsche reflects in Beyond Good and Evil: ‘He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster.’ As Hopper’s photographer observes about Kurtz in Apocalypse Now: ‘The man is clear in his mind, but his soul is mad.’

The idea that becoming one’s truth may result in self-destruction and madness characterizes the third aspect of truthfulness expressed in Edwards’ posthumously published lyrics, embodied by the third stage in which they were released: Manic Street Preachers’ ninth studio album Journal for Plague Lovers (2009). All lyrics on this album were composed of texts, poems, haikus and prose that Edwards, weeks before his disappearance, gave to his band mates. This resulted in lyrics that are fragmented, often difficult to understand, reflecting a mind that has difficulty with clinging to one fixed grip on reality. These lyrics are filled with references to cultural icons as diverse as Spinoza, Marlon Brando, Noam Chomsky, Heinrich Himmler, Ingres’ painting Grande Odalisque, the Newspeak dictionary in George Orwell’s 1984, the films The Entertainer and Reflections in a Golden Eye, and countless more. The following song, ‘Peeled Apples’, forms an example of the fragmented nature of these lyrics:

Furthermore, Edwards left these lyrics with the films Equus and Naked – both revolving around troubled men who are unable to fit in society, slip into different forms of insanity, but do not lose their critical influence on people (as illustrated by the quote above this paper, in which a psychiatrist reflects on the protagonist of Equus). Just before his disappearance, Edwards was also fascinated by the 1934 Novel With Cocaine, written by a mysterious Russian émigré under the pseudonym of M. Ageyev, who disappeared after the success of his novel.

Many phenomena in the web of references in which Edwards embedded himself, in other words, revolve around madness, loneliness and disappearance. The notion of madness and Edwards’ experiences in mental institutions are reflected as well by several songs on Journal for Plague Lovers. The song ‘Facing Page: Top Left’, for example, opens with a description of the monotonous, hygienic and fake nature of daily life in an institution, but transforms into a nihilistic expression of weariness and boredom with existence in general. ‘She Bathed Herself in a Bath of Bleach’, in turn, may have been inspired by a story Edwards heard in the institution, and describes a delicate and vulnerable person who harms herself to please someone she loves. ‘Virginia State Epileptic Colony’, furthermore, refers to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, which was opened in 1910 by a group of infamous eugenicists. The lyrics refer to the illusion of freedom, to lobotomy and to the attempt to draw a perfect circle. In an interview in 1992, Edwards referred to Vincent Van Gogh’s reflections on drawing a perfect circle as well and observed: ‘The only perfect circle on the human body is the eye. When a baby is born it’s so perfect, but when it opens its eyes it’s just blinded by corruption and everything else is a downward spiral.’ The attempt to draw a perfect circle seems to symbolize the Nietzschean attempt to independently create something absolutely pure, something that transcends humanity, constituting a critical yardstick to measure the ‘impure’ world by.

What makes many of the lyrics published on Journal for Plague Lovers specifically helpful within the context of this paper, however, is the ambivalent attitude they express towards religion and towards Christianity in particular – an ambivalence that echoes Nietzsche’s last writings, described above. The song ‘Journal for Plague Lovers’, for example, ends with the expression of a religious longing for absolute norms, claiming that only a god can bruise, sooth and forgive – a sharp contrast with Edwards’ claim in ‘Judge Yr’self’ that one has to find, face and speak one’s own truth. ‘All Is Vanity’, furthermore, takes both its title and its inspiration from the book of Ecclesiastes in the Old Testament, which describes the meaningless and repetitive nature of life, containing the famous phrase that ‘there is nothing new under the sun’. The song’s lyrics again describe the monotony of human life, and Edwards states that he only wants one truth and does not mind if he is being lied to, seemingly longing for a religion that, in Nietzsche’s words, was based on ‘the art of holy lying’. In November 1994, Edwards claimed in a similar line that he was fascinated by humanity’s longing for a god, quoting Camus that everyone wants to die a ‘happy death’ and citing William Blake’s claim that ‘The cut worm forgives the plough and dies in peace’. Desperately, it seems, Edwards here seeks to want to cling to an entity that enables him to strip himself of all vanity and reach a form of purity and discipline within a context that is experienced as sinful, impure and wrong.

Again, he emphasized this idea with help of body art: he had two maps based on Dante’s Divina Comedia tattooed on his arms, one depicting its universe – Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso and Jerusalem at its centre – the other showing the ninth circle in Dante’s Hell. This circle famously consists of a frozen lake divided into four rings that hold several kinds of traitors. In the last ring, Satan is frozen into the ice, unable to escape, punished for his treachery against God. Figure 2 shows Edwards’ tattoos, including the above-mentioned ‘Useless Generation’ and the reference to Apocalypse Now:

These ambivalent religious references in the lyrics used for Journal for Plague Lovers and on Edwards’ own body, however, are contrasted by a more aggressive and negative attitude towards Christianity, often combined with ideas about pain. The lyrics to the song ‘Peeled Apples’ (see the video embedded above), for example, expresses an obsession with the cleansing nature of self-harm and pain, referring to digging one’s nails out and to the Nietzschean idea that one should trespass one’s torments if one is ‘what one wants to be’. Furthermore, the original lyrics sheet printed in the booklet of Journal for Plague Lovers contains the phrase ‘Virescit Vulnere Virtus’ (a quotation taken from the Roman poet Aulus Furius of Antium, meaning ‘courage becomes stronger through a wound’). ‘This Joke Sport, Severed’, in turn, ends with the claim that the procession of the flagellants is all that the Lamb of God achieved. The flagellants were a group of religious zealots in the Middle Ages that tried to find redemption and atonement by whipping themselves. Claiming that the ‘Lamb of God’ (a title for Jesus used by John the Baptist: ‘Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world.’) has only achieved the procession of flagellants, could therefore be read as a Nietzschean critique of Christianity’s emphasis on sin, suffering and self-harm and its inability to turn suffering into a sign of strength and power. As Nietzsche cynically observed in The Antichrist: ‘The fear of pain, even of the infinitely small in pain, – cannot end otherwise than in a religion of love…’ It may also form an explanation for the title Journal for Plague Lovers: expressing a love for the plague emphasizes the strength of self-harm, the power manifested by being able to endure pain, to embrace one’s fate by taking control of it, and to become one’s own truth. ‘Doors Closing Slowly’ contains an even more aggressive attack on Christianity, stating that the cross is the shadow and that crucifixion is ‘the easy life’, urging the listener to remove ‘the lamb’ from his or her thought. Furthermore, the lyrics refer to the falseness of the religious community and to the violence of the Bible, describing Lazarus as burning Jerusalem and referring to the prophet Isaiah’s violent speech to Hezekiah about his blasphemy against ‘the Holy One of Israel’. The song also aims to undermine the language of the Bible by claiming that the merciful cast the last stone, and asking who throws the first stone if the stone ‘is you’.

This last statement can be understood as a summary of the third and last dimension of the critical notion of truth I have discussed in this paper: self-destruction. By stating that one can be the stone that is cast, Edwards expresses the desire to overcome the morality that exists between human beings by overcoming his own human nature and turning himself into a non-human object; an object that causes pain and may shock others into thinking, into a critique of their own humanity. Phrasing this idea within a religious context – a context revolving around sin, treachery and Dante’s hell – Edwards keeps returning to Christian ideas, as did Nietzsche before he slipped into insanity, struggling with the inability to truly overcome himself.

Conclusion

With help of Walzer, I have argued that the critic needs to constitute a distance between herself and that which she aims to criticize. I have shown that Nietzsche tries to create this distance by developing a particular notion of truth, which he links to his own body and his individual existence as a corporeal being. This notion of truth is characterized by three dimensions: vulnerability, militancy and self-destruction. I have then argued, with help of Bataille’s analysis of Nietzsche’s madness, that this form of critique is so particular and tied in such an intricate way to a specific body and mind that it seems unrepeatable. However, I have aimed to show that the realm of the arts, and more specifically the realm of modern, popular music, might form a fruitful ground for this kind of critique to be formulated again, because in this realm the particular mind, body and life of the artist are often entwined with the lyrics that the artists writes and the truth she aims to express.

To illustrate this idea, I have discussed the example of Richard Edwards and argued that the three aspects that I linked to Nietzsche’s ideas return in the three stages in which his posthumously released lyrics can be divided: firstly, these lyrics contain a longing for a divine and idealized truth in a universe that remains empty and a world that is false; secondly, they express the attempt to turn oneself into one’s own truth and aggressively turn against everything and everyone else; and finally, they reflect a fragmented and corroded state of mind characterized by an ambivalent stance towards religion.

It is important to emphasize that I do not claim that all popular musicians embody this form of critique or that it can only be formulated within this realm. Nor do I want to argue that the way in which Edwards presented himself as an embodiment of his ideas and lyrics is the only way to formulate this critique, or that everything he said and wrote can be understood within a Nietzschean framework. I have shown, for example, that whereas Nietzsche mainly depends on his own writings to constitute himself as a sun in a sunless world, Edwards uses countless references to cultural phenomena to strengthen the critical truth he aims to express, thereby embedding himself in a network of references and ideas of which he himself formed the critical center. Nevertheless, I have hoped to show that Edwards provides us with an example of a Nietzschean form of critique in the modern age, and I am convinced that the framework used to approach his ideas can be used as well to interpret other artists, both within the realm of modern, popular culture and outside of it.

Notes

- Michael Walzer, Interpretation and Social Criticism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1987), p. 3.

- Ibid., pp. 10-11.

- Ibid., p. 61, my emphasis.

- Ibid, p. 21.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science. Transl. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books (1974), pp. 181-2.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is & The Antichrist: A Curse on Christianity. Transl. Thomas Wayne. New York: Algora Publishing (2004), p. 40.

- Nietzsche, The Gay Science, p. 223.

- Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, p. 98.

- Ibid., p. 92.

- Ibid., pp. 11-12.

- Ibid., p. 90.

- Ibid., p. 90.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book For All and None. Transl. Walter Kaufman. New York: Penguin (1978), p. 13.

- Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus. Transl. Justin O’Brien. New York: Vintage International (1991), p. 6. Manic Street Preachers cited this line in the booklet of Generation Terrorists.

- The Holy Bible. King James Version. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson (2011), John 14:6.

- Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, p. 195.

- See Julian Young, Friedrich Nietzsche, A Philosophical Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2010), pp. 529- 30.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. Transl. R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1991), p. 14.

- Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, p. 8.

- Georges Bataille, ‘Nietzsche’s Madness’, in OCTOBER 36: Georges Bataille, Writings on Laughter, Sacrifice, Nietzsche, Un-Knowing, Transl. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (1986), p. 45.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- In his biography of Nietzsche, Young notes that both Jesus and Dionysus overcame death (Dionysus was killed by the Titans and then resurrected). He furthermore observes, in line of Bataille: ‘The ecstatic side of Nietzsche’s madness can […] be described as an entry into the Dionysian state that is the foundation of his philosophy’ (Young, Friedrich Nietzsche, p. 530).

- See for an analysis of this aspect of Dylan: Steven Heine, Bargainin’ for Salvation: Bob Dylan, a Zen Master? London: Bloomsbury (2009).

- See for a critical exploration of Manic Street Preachers’ first three albums: Mathijs Peters, ‘Adorno Meets Welsh Alternative Rock Band Manic Street Preachers: Three Proposed Critical Models.’ The Journal of Popular Culture. 48, 6, pp. 1346-73.

- See ‘Manic Street Preachers – Slash ‘N’ Burn’. Youtube.com. 14 Jan. 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8a1WEjLqUw. Last visited: 6 Feb. 2017.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits. Transl. R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1996), p. 329.

- See No Manifesto, Dir. Elizabeth Marcus. Wibblywobbly Productions (2015).

- Jason Eccles, ‘The Manics Holy Bible’, in Examiner.com, April 20, 2013. http://www.examiner.com/review/the-manics-holy-bible.

- See ‘Richey Edwards’ last tv interview part 1’. Youtube.com. 7 Dec. 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rnJ5nkju0gQ. Last visited: 6 Feb. 2017.

- Simon Price, Everything (A Book About Manic Street Preachers). London: Virgin Books (1999), pp. 132-3.

- Ibid., pp. 188, 197, 203; Mike Middles, Manic Street Preachers. London: Omnibus Press (1999), p. 158.

- See Price, Everything, pp. 174-92; See for a detailed description of Edwards’s last days: Rob Jovanovic, A Version of Reason: In Search of Richey Edwards. London: Orion Books (2009).

- Price, Everything, p. 178, 203.

- Ibid., p. 198.

- As quoted in Anne Stevenson, Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath. New York: Viking (1989), p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Sylvia Plath, The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath. London: Faber and Faber (2000), p. 199.

- Sylvia Plath, The Collected Poems. Ed. Ted Hughes. New York: Harper & Row (1981), p. 152.

- Tennessee Williams, The Collected Poems. New York: New Directions, (2002,) p. 17.

- Price, Everything, p. 175.

- See Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of Manic Street Preachers. London: Sony Music Entertainment (2003). The title of this collection was inspired by the subtitle to Greil Marcus’s 1989 book on popular music, punk, critique and movements like Dadaism, Lettrism and Situationism called Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century.

- See ‘Manic Street Preachers – Judge Yr’self’. Youtube.com. 14 Nov. 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m14pt9necao. Last visited: 6 Feb. 2017.

- Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, p. 116.

- Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, pp. 90-1.

- Price, Everything, p. 167.

- Ibid., p. 125.

- Yukio Mishima, Sun and Steel. Transl. J. Bester. Tokyo: Kodansha International (2003), p. 22.

- Ibid., p. 11.

- As quoted in H.S. Stokes, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company (1975), p. 184.

- See ‘Yukio Mishima Speaking In English’. Youtube.com. 8 Oct. 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DPAZQ6mhRcU. Last visited: 6 Feb. 2017.

- Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, p. 39.

- Price, Everything, p. 165.

- Taken from Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell & The Drunken Boat. Transl. Louis Varèse. New York: New Directions Books (1961), p. 3, 13, 27.

- Apocalypse Now. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. United Artists (1979).

- Ibid., pp. 151, 161, 177.

- Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness. Los Longeles: Green Integer (2003), p. 171.

- Ibid., p. 171-2.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. Transl. Marion Faber. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1998), p. 146.

- See Manic Street Preachers, Journal for Plague Lovers, 2-disk Deluxe Edition. London: Columbia (2009).

- See ‘Manic Street Preachers – Peeled Apples’. Youtube.com. 9 May 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4mL_YAJG_c. Last visited: 6 Feb. 2017.

- Price, Everything, p. 189; Clarke, Sweet Venom, p. 132; Middles, Manic Street Preachers, p. 155.

- In a letter to Emile Bernard, Van Gogh writes about the Italian painter Giotto di Bondone, who, based on his ability to draw perfect circles freehand, was invited to paint scenes in the St. Peter: see Vincent Van Gogh, Ever Yours: The Essential Letters. New Haven: Yale University Press (2014), p. 562.

- Wordsworth’s quote ‘The eye, it cannot choose but see’, cited at the beginning of the video-clip for ‘Kevin Carter’, could be placed in this context as well.

- The Holy Bible, Ecclesiastes 1:9.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist. Transl. R.J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin (1968), p. 169.

- Price, Everything, p. 166. Taken from William Blake, ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, in Selected Poetry and Prose. New York: Perason (2000), p. 131.

- The Holy Bible, John 1:29.

- Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist, p. 154.

- The Holy Bible, Isaiah 37:21-23.

Cite this Article

https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/031.e08