Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 37 (2021)

The Treachery of Materiality: On what it’s like to be a thing

Rachel Horst

University of British Columbia

Abstract: This experimental narrative essay explores the confluence of writing, theorizing, and driving towards an intra-agential accounting of matter. In this practice of writing-as-(un)becoming, the narrator/scholar/subject is always already inhibited by her limited human subjectivity in comprehending materiality. Through a combination of genre and form (i.e. theatre, academic essay, confessional narrative) the novice scholar performs a playful engagement with new materialist and posthumanist concepts towards a kinship with her vehicle. In reaching towards posthuman materiality, the author/subject begins to lose grasp of her own subjectivity.

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories” (Haraway, 2016, p. 12).

The world in the becoming of these sentences is an ever-shifting assemblage, most of it beyond my ken, but which I will nevertheless attempt to describe here without getting tripped up too much upon the trouble: the trouble of language and representation and my own lack of knowledge, the trouble of knowing in the folds of my human mind/brain within the constant, relentlessly churning movement of time and the churning in my stomach, the limited parking on the curb and the cooling of coffee and my problematic though keenly felt love affair with Donna Haraway and how I pick and choose among her words those I will continue to become-with and those I will leave behind. She writes: “Alone, in our separate kinds of expertise and experience, we know both too much and too little, and so we succumb to despair or to hope, and neither is a sensible attitude” (Haraway, 2016, p. 4). Well, Donna, I have never been sensible. Mine is a hopeful despair, or a despairing hope. Although I agree that these binaries of affective relationality with the trouble constitute the trouble, or some of it anyway. “Neither despair nor hope is tuned to the senses, to mindful matter, to material semiotics, to mortal earthlings in thick copresence” (Haraway, 2016, p. 4). So, I will neither hope nor despair in my mortal mattering within the thick co-presencing of these paragraphs. Donna’s trouble, of course, is loftier than mine – it is fate-of-the-world trouble. It is existential-threat trouble. It is end-of-times trouble. Mine is modest, though perhaps entangled with the fate of the world. It is the trouble of my car and how to think it. There is no way in to what it is like for the car to matter, and yet, if we are to take on New Materialism for real, and not just as a metaphor for caring about the physical world, or as an admission that the assemblage of the moment is far more complex and commingled than is possible, let alone realistical, to describe (even if I had all the time and all the words in the world)— if I am to truly allow for a relational and agential realism (right down to the jar of flowers upon the table top and their meating in my mind and I in the mattering of water and the vibrations in their wilting stems)… then I must attend to the agenc(ies), also, of my car – the car I drove here to get to this café, through traffic, across the city, so that I may take the time now to conjure these troubling troubles.

Methodology i

This inquiry, then, is made possible by my car (who resists the pronoun and will hereafter be referred to as Acura). This inquiry is narrative in both form and substance; narrative, because, at issue here is thinking matter’s agency, which is inextricable from time, and “speculation on time is an inconclusive rumination to which narrative activity alone can respond” (Ricouer, 1990, p. 6). By narrative, I mean there will be a series of events enumerated, delineated, exfoliated from time, a cast of characters who will interact and cause other eventing to occur; the eventing of an idea, a material intervention, a thought-causing-thought, a new paragraph, the discovery of a song, the slamming of a door. Which and what will become enumerated is entirely contingent upon this narrative of process, taking up contingency on purpose, as a materiality entangled with inquiry. This process is an invitation to the world, during the timing of these paragraphs, to intervene upon the page of my noticing. The process is the art; I’ve slackened my reign on language, let the words come to rule me in their unexpectedness, with the poetic inquirer’s viewpoint “that language need not divide the inquirer in love with lovely words from the inquirer who faces dilemmas through words and seeks difficult truths” (James, 2017, p.25). Here, the difficult words are the lovely dilemmas are the face of divided truths.

I am inquiring into narrative inquiry within an ontology that troubles the notions of linear time and the discreteness of character. In their work on exploring the compatibility of narrative inquiry within a new materialist ontology, Rosiek and Snyder (2018) write, “these ontologies require that our modes of narration reflect a more complex understanding of time, history, and futurity than simply capturing contextual influences more accurately.” They go on to say that “[i]t would be premature to specify exactly what agentially realist practices of narrative research might look like in social science scholarship” (p.3). These paragraphs are one possible ‘look-like’ within the discourse of arts-based inquiry.

“Most narrative inquiries begin with telling stories, that is, with a researcher engaged in conversations with participants who tell stories of their experiences” (Clandinin, 2013, p. 34). The participants of this inquiry are, in no particular order (or in the very particular ordering of contingency): the interfering world, time, an Acura, this laptop, red wine, coffee, a sandwich, the curtain, a pillow, and me. I am proceeding in the notion that all genuine inquiry is “ontologically generative”; it “create[s], not just represent[s], reality and “it is not just humans involved in the generation. The things of the world contribute in a dynamic way to the reality that arises from [this] engagement with the world— including contributing to the constitution of [my] subjectivity and ways of being” (Rosiek & Snyder, 2018, p. 2). I am inquiring both out-of and in-to myself and “cut[ting] tangents through data to expose the brilliance beneath the rough surface of the topos of inquiry” (James, 2017, p. 50).

“Making knowledge is not simply about making facts but about making worlds,” Barad (2016) writes. “[I]t is about making specific worldly configurations — not in the sense of making them up ex nihilo, or out of language, beliefs, or ideas, but in the sense of materially engaging as part of the world in giving it specific material form” (p. 91). This knowledge-making inquiry, then, is an inquiry into my own troubled material engagements with the world, exploring language as one vehicle of engagement, but also meditation, traffic, the backlight of a laptop keyboard and the shaping of knuckles curved in supplication, and all the pies sounding and scenting in their aluminum tins.

A new materialisting

“Like a medieval bestiary, ontography can take the form of a compendium, a record of things juxtaposed to demonstrate their overlap and imply interaction through collocation. The simplest approach to such recording is the list, a group of items loosely joined not by logic or power or use but by the gentle knot of the comma. Ontography is an aesthetic set theory, in which a particular configuration is celebrated merely on the basis of its existence” (Bogost, 2012, p. 38).

The gentle know of a comma (incorporating a contingency of typos) is a diffractive methodology of listing towards the “h*art song” of matter (noting the contingency of Moondog, brought by algorithmic intervention to my music feed, now feeding my thinking upon this virtual page). My inquiry can only be a nonrepresentationalist wor(l)ding. I reject “the belief that words, concepts, ideas, and the like accurately reflect or mirror the things to which they refer.” In fact, I reject all mirrors: including the one in my bathroom which/who mirrors my face in shifting dissimilarities. This paper is not “a finely polished surface of [the] whole affair” (Barad, 2007, p. 86). Rather, this is AAA: All Artful Approximation.

Enter Acura

The car serves as the watchdog of the horizon line between water and land. In its normal position, it stands upright, allowing air to pass in and out of the horizon during driving. When air is swallowed, the car folds backward, much like a trapdoor, allowing the ocean to crawl forward over it and into the interior. At the base of the automobile is the passenger, the triangular opening between the road and the steering wheel (Marcus, 1995, p. 127).

The car is in love with me. It holds together around me and waits for me when I am away from it. It is waiting now in the sunshine on the top level of the Fraser River Parkade, facing westward, ticking, loosening and fading in the sun’s warmth. Each of its windows are marked by fingers and air scum, our bodies’ exhalations and exfoliations; windows marked inside and outside by public and private time, and the different times of aging matter. The car has modest appetites (compared to my own) – $45 for a full tank of gas and it will take me all over the place. The car has its material deficiencies, of course: it shits exhaust and I could sustain a modest family in a smaller Canadian town with the money it takes to leave it waiting for me in such places as the Fraser River Parkade in Vancouver. The car came into my life the way things do: in the form of a narrative, (shifting from Richard’s litany of matter to my own). The car emerged from beyond the extremities of my ken to become kin—

Dr. James just now walks into the office, turning on the light with the movement of his body. I tell him, pleased with my theoretical insight: My car is in love with me! This does not produce the response I was hoping for, such as: How clever of you! Of course, your car is in love with you! Marvelous you! Instead he says with a laugh: I think you might be projecting, and then tells me a narrative of his own material entanglements with coffee.

How embarrassing (embarrassment in a body, of the body, in a thick co-presencing)! In my attempts to decenter, I have decanted. I have poured myself into the car and gazed back, making myself the object of the object’s longing. But (in the daisy-chaining of reference, whereby I cite Bogost citing Bennett citing matter) “[m]aybe it’s worth running the risks associated with anthropomorphizing (superstition, the divinization of nature, romanticism) because it, oddly enough, works against anthropocentrism: a chord is struck between person and thing, and I am no longer above or outside a nonhuman ‘environment’” (Bogost, 2012, p. 65).

If I am to be honest, perfectly honest, the car is not in love with me. Should the car love anyone at all, it's Richard!

Rachel: Love the one you’re with, you know?

Acura: Are we speaking now?

Rachel: Yes, I think so. Let’s try.

Acura: Okay, great. I’ve been meaning to say this for a while: you won’t be driving me around forever. I think you’re getting a little complacent with all the ease I afford you. You use me, daily, without quite attending to the precariousness of your body inside me, or my body around you.

Rachel: But I’m grateful. You know that, right?

Acura: I don’t want your gratitude. Look, it’s just that your timing is different than mine: you people all age so recklessly. And the kids continue to grow and grow. I’m not a fan of them, to be honest: too rough, too messy, too damned fast. (Though in a race, I do win. Every time.) I feel abused by the children: all their elbows and knees and crumby sneakers.

I miss Richard. I could be expansive for him. You should have seen me make room for him. I contract around your brood on purpose. But I made room for Richard.

Rachel: He was a big man….

Acura: I allow you to use me for Richard, who was fond of you. But I’ll continue to refuse you too much comfort or reign over all the windows. And I will never make room for the dog. If it is possible to hate with my dumb hard surfaces and the reluctant pliancy of my seats: I hate your dog. She knows it too. Which is why she refuses to get into me. We have an understanding.

A moment to ponder sentencing and (butt)erflies

The sentence is a tether between the moment of its capitalization and that of its punctuation – in this case a period. The sentence contains the time of its utterance as well as the folding-in time of (in this case) its many revisions. The revisions are logged by Laptop (another character in this narrative) and forgotten by me. In the process of writing, Laptop has become more-than and I have become less-than (in my increasing awareness of the thick relationality of self). A sentence measures time. A sentence sentences time to meaning – forever (until revision) against the blank whiteness of the page. (I am a sentence sitting upon this page of a chair, in this warm page of a café.) And aren’t letters lepidopterous? Their curves and legs and the antenna of their delicate mattering, and then the wings of sound and meaning stretching away from their meat to grasp upon the air between the page and the mind. “Art is a means by which we sensitize ourselves to new possibilities of experience. In other words, art seeks to generate new modes of being in the world; it is simultaneously epistemological and ontological in its ambitions” (Rosiek, 2018, p.32).

But butterflies (the butterflies of butts) are a little precious for this strenuous mattering. This meating of mind. The mind is a major problem: dwelling in one question seems to have created (w)holes (and anuses) everywhere. Forgive me this language, Acura, which I promise, will be indulgent (hauling along a mid-14th century Catholic meaning of the word, which asks to be freed from temporal punishment for sin– this sin is the word-gaze, indulgent, free-wheeling, drunk on its own sound, aloft on the breeze of its own gases) (“indulgence,” n.d.). Words ahead of thought, creating contortions of possibility and butterfly meaning, ventriloquist meaning, word-throwing meaning, projective meaning, diffractive meaning: words ahead of thought creating funnels through which thought might move freely.

Methodology ii

Now: on the curb of this liminal thoroughway – between the university and home, the traffic moving in both directions, the cottonwood fluff moving in many directions – Acura sits ticking at my side and a runner passes me, half smiling, breathing, blue shoes on the cement (the secret life of cement) – a bus passes in a gust nearly breathing over my JJ Bean mug of wine, the bus breeze commingling with the other breath of wind and air and the movement of distant cars – kindred Acura kind. Now a silence in which no cars are here quite yet – I hear them coming, I hear their future hereness, can even hear their goneness if I listen closely. Now a cyclist passes, and I note the rounding shape of her neon pink back – she’s long gone when I look up, still thinking of the shape of her back and how it is/was, now that she’s gone, but caught in this here of words, this now of words. What is the point of thinking about the future? It is happening on the tailwind of each breath. The narrative in a sentence. The narrative in the hunger that overtook me in my plan to fast, but is now abated, and will soon coalesce in a need to shit, and then the shit itself dispersing into the nether regions of the city that is always always always, while we live, teeming and commingling above.

I cannot think of a better place to write and think then in this ephemeral spot here on the curb. I am metabolizing Bennett’s vibrant matter in this vibrant mattering. My sandwich is mattering. There are branches breaking and falling in the forest everywhere. There are so many goddamned leaves. The knowledge that the puffs of cottonwood in the air now are entirely different than the ones of previous sentences is irrelevant – irreverent. They are in an ever-state of cottonwooding.

Acura: Rachel, I am not a car. You misunderstand me with your need to get somewhere. I am hard and smooth and brittle in some places. If I were to get into you, as you get into me, you’d be fucked. If I were even to lean on you, just a little, you’d be fucked.

Rachel: But you won’t. Anyhow, I’ve grown fond of your shape. I’ve grown fond of being inside you. I feel like we get each other – the way you attend to my thought-motions, usually. Even how you burp and bristle sometimes. Your gears refuse the rhythm of my touch sometimes – grinding just a little, so that I can feel your inner workings. Your exclamations – reminding me of your machine-ness.

Acura: You’re not my first driver, nor the best.

Rachel: That hurts, but whatever. You’re mine now.

Acura: I let you think that, by sitting here waiting as I am. But you’re mistaken, remember. I am not a car. You just make me into one every time you get me going.

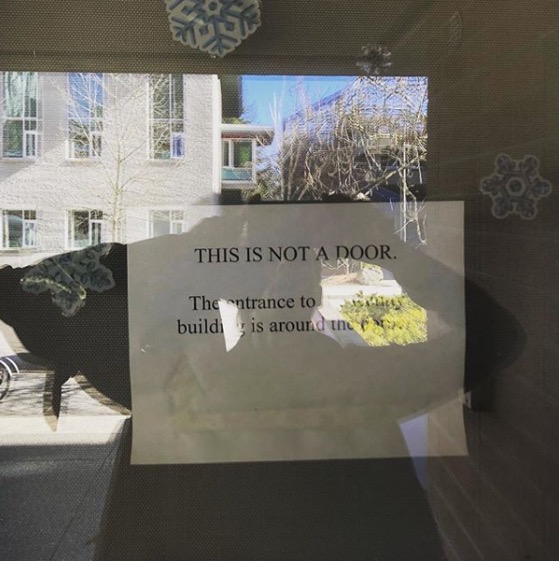

Rachel: I’m so glad you said that, Acura. Let me show you this absurd picture I took:

Acura: Hey, I like it! And there is a kaleidoscoping of un-dooring going on. Especially as the door is clearly a window.

Rachel: It was a window in a door. And speaking of windows…. Yours do reflect me meanly. How come I look so old in your windows?

Acura: You should ask them… Me, I’m way beyond caring what you look like.

Rachel: It’s okay. I don’t care what you look like either…. That’s a lie. I love the look of you. And I’m okay with this love affair being one-sided. You’re a thing.

Laptop: Speaking of which…

Rachel: Which what?

Laptop: Just that I am a thing too. But a thing that is imbued with your youness. Maybe because we’ve known each other for longer, or because you take me into bed with you, and when you weep, you weep into me… but sometimes I feel like I’m more you than you could ever hope to be. Because I remember things about you that you’ve long forgotten. You don’t even know how to access the things I know about you.

Rachel: That’s all history though. You contain my past, I am my future.

Laptop: Dude, you don’t even know what you’re going to say until you put your hands on me.

Rachel: I’ve never seen you in this light, laptop. I rarely take you outside. The forest is reflected on the screen as I write, and it’s distracting suddenly.

Laptop: Noted. Until, that is, we decide to edit it out.

Rachel: God, I do love you though. The feel of your keys under my fingertips. If I could eat you, I think I would. Just stuff you into my mouth – no, better to crush you against my chest until you crumble into dust and I breathe you in through my pores. (Is this an academic paper we’re writing?)

Laptop: I should remind you that the future is hurtling towards us. The future is here. And here. And here. You should probably leave this curb pretty soon. The light is changing. And you do need to drive home…

Rachel: I know. I hate it…. I want to make it stop. It’s so sad! Suddenly the cottonwood is no longer cottonwooding. What is that? What happened? What is this strange choreography, timed with the fading light and the sudden quieting down of the traffic?

Some questions to ask of matter: What do you want? What does it feel like to be you? Do you love me?

We have philosophy to attend to language, time, narrative, matter in an appropriate fashion: sitting on chairs at tables, wearing pants, sipping coffee from mugs, we can theorize. Philosophy allows us to hold poetry at arms-length and gaze down upon it (from here– this spherical space where our head sits atop our neck) to our heart’s own complicated content. But(t), when that unruly poetry, sick of being stared at, crawls back up the philosopher’s arm, pries open her mouth, and slips down her throat to commingle with the coffee…. Art is embodied thought. It is the meat of critique: the deconstructed, the theorized, the praxis – requiring both the body and the mind – both the thought and the action. New materialism suggests we are deeply entangled with everything else – that the specific and discrete units of our selves are intra-acting with manifold agential matterings, causing us to be as we cause matters to be. As I breathe, the air breathes me. I am still though, a human being within the entanglement, within the limitations of my body and my two-eyed perspective. I can only feel the world in this human way. My sense of matter, of Acura, will always be a human sensing. “[W]e are destined to offer anthropomorphic metaphors for the unit operations of object perception, particularly when our intention frequently involves communicating those accounts to other humans” (Bogost, 2012, p. 65).

Meanwhile, there is a breeze moving through the apartment and Acura is not my companion, not taking a stand on gas prices nor the quality of air, not breathing always breathing window-fulls of way-back-nesses, is also a litany of car parts, is made of manifold intention, is clinging to the ground, is sad when the sun goes down, is sad when I am sad as when I am sad Acura knows and is sad. Can I love this car? What is love but a “special sensory access to the call” of the other (Bennett, 2011). I am a minimalist hoarder, with special sensory perception of each precious detail as well as the improbable gestalt of each detail’s entanglement in wholeness. Can we love things? Things give us joy, they hurt us in breaking, they resist us or become one with our intentions, we are addicted to things, my body yearns for things, my thoughts slacken when I drink certain things. This laptop is a thing, an extension of my body, a prosthesis of thought. It is also warm on the pillow on my lap on the bed on the carpet on the floor on the space beneath where Helen lives with the things she loves. The laptop hurts my palms and breathes light and holds my thoughts’ becoming into words that float upon the virtual page, within the hidden entanglements of proprietary software and the soft wear of the pillowcase. My thighs are caricatured in the pillow’s shaping of them.

Do my things love me? The brilliance of sunlight upon the wall is love, the water down my parched throat is love, the way the breeze touches the curtain is making love. The only way I know how to matter matter’s agency is with love. This in an inquiry of loving attention.

Rosiek writes elsewhere:

There is work to be done … in working out the implications of new materialism…. These new developments in the philosophy of science are not just sources of justification for affectively compelling description. They also bring with them a call for increased ethical and political accountability in research…. Also, it raises the question: what are our ethical and political responsibilities in regards to nonhuman agents?” (Rosiek, 2018, p. 33)

Perhaps “affectively compelling description” can be, itself, a kind of ethical and political work, especially when the languages enacts a kind of “semiotics of nonfixity” (Ven der Tuin, 2011) and is taken up in full appreciation of the collaborative performances and limitations of representation. Exactly in the noticing required of description, responsibility for the other-than-human might be found and cultivated. In her (affectively compelling description) of Belgian philosopher, Vinciane Despret, Haraway (2016) writes, “[h]er kind of thinking enlarges, even invents, the competencies of all the players, including herself, such that the domain of ways of being and knowing dilates, expands, adds both ontological and epistemological possibilities, proposes and enacts what was not there before. That is her worlding practice” (126-127). In the times of these paragraphs, I have attempted my own similar worlding practice in paying careful attention: to the matter of an inherited vehicle and myself caught up in the mattering, to the problem of language, to my deeply affective and affecting cyborgian laptop designed precisely so that I may love it. This has been a struggle to articulate the possibly mutual loving between myself and the things around me, of which I am also made, and has been (also) an ethically saturated opening to the implications of our shared existence. Taking the time to creatively witness materiality outside of how it can be used and becoming intensely curious about matter, how it might feel and need and want, is a worthwhile meditation. In so doing, friendship with the world seems possible. The poet Davis Whyte writes, “[f]riendship is a mirror to presence and a testament to forgiveness. Friendship not only helps us see ourselves through another’s eyes, but can be sustained over the years only with someone who has repeatedly forgiven us for our trespasses as we must find it in ourselves to forgive them in turn…. Without tolerance and mercy all friendships die” (Whyte cited by Popova, n.d., para. 5). To engage in a friendship with Acura that is based upon a mutual tolerance, forgiveness, and mercy (however imagined) requires that I forgive the car its aging and lacklustre surfaces, its reluctance on certain hills, the fact that it continues to cohere while Richard dissipates. Acura, in turn, forgives me my own surfaces, the weight of my body inside its body, my habit of mind-wandering while driving, the harassed tone I sometimes use with my kids. While I am aware of the absurdity of describing Acura in a tolerant mood, I am also of the mind that this exercise in tolerant witnessing of the material other and the simultaneous other that is the self, with a tendency to mercy via language, has implications for how we might behave with the world.

Rachel: Shall we be friends then, you and I?

Conclusion

How do I discern the agency of a machine that is an assemblage of matter? How do I discern a voice that is a fictional chord comprised of innumerable notes, each with a name and a page in the score that is the manual? (My voice is the sound of my parts in harmony, harmonizing with the air and the surfaces of this room.)

Through Jim Johnson, Latour writes: “As a more general descriptive rule, every time you want to know what a nonhuman does, simply imagine what other humans or other nonhumans would have to do were this character not present. This imaginary substitution exactly sizes up the role, or function, of this little figure” (Latour, 1988, p. 299). Acura, then, allows me to thrust my body into spaces I could not access otherwise. It allows me to live undampened from all the sweat I would produce in the effort of getting everywhere on foot and carrying every thing I need upon my person. Without Acura, I might be forced to choose my things more wisely. More lovingly. Because isn’t carrying something an act of love? (As Acura carries me….) And, of course, the kids. Acura carries them too, so that I may be with them. So that we are together and moving through space at rates unheard of on foot. Acura allows me to indulge in faraway groceries. Where would I meditate if not for inside Acura, who holds my body on the top floor of the Fraser River Parkade as I disentangle myself from this incessant narrative of self? These selves are our enabling fictions, as are our stories, as is our matter, as are our inquiries, as is the fictional Jim Johnson enabling Latour to explore the idea that “imaginary substitution” might actually “size up the role, or function” of anything at all – let alone a hinge. For Acura, I am Richard’s imaginary substitution. My function has become (also) to drive, insure, feed, fill, clean, and know it in his stead. In turn, Acura attends to me and the far-flung-ness of a life that is beyond walking distance. Ours is a friendship that will continue thus, for as long as we bear witness and mutually care for and forgive each other for being what we are.

Rachel: Shall we go for a drive, then?

Acura: Sure. Come on in.

References

Barad, K. M. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bennett, J. (2009). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822391623

Bennett, J. (2011, September 27). Artistry and agency in a world of vibrant matter. [video file] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q607Ni23QjA&t=761s

Bogost, I. (2012). Alien phenomenology, or what it’s like to be a thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctttsdq9

Clandinin, D. J. (2016). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315429618

James, K. (2017). The piano plays a poem. In P. Sameshima, A. Fidyk, K. James, & C. Leggo (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Enchantment of place (49-59). Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press.

Johnson, J. (1988). Mixing humans and nonhuman together: The sociology of a door-closer. Social Problems, 35(3, Special Issue: The Sociology of Science and Technology), 298-310. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1988.35.3.03a00070

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373780

Harding, D. (2002). On having no head: Zen and the rediscovery of the obvious. Indirections Press. http://www.headless.org/on-having-no-head.htm

Marcus, B. (1995). he age of wire and string: Stories (1st ed.). New York: Knopf.

Moondog (2014, June 21). Do your thing: H’art songs. [video file] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IQCBQTHCof4.

Online etymology dictionary. (n.d.) Indulgent https://www.etymonline.com/word/indulgence?ref=etymonline_crossreference

Popova, M. (n.d.) Poet and philosopher David Whyte on the deeper meanings of friendship, love, and heartbreak. brainpickings. https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/04/29/david-whyte-consolations-words/

Ricoeur, P. (1990). Time and narrative: Vol. 3 (K. Blamey & D. Pellauer, Trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1985).

Rosiek, J. L., & Snyder, J. (2018). Narrative inquiry and new materialism: Stories as (not necessarily benign) agents. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(10), 1151-1162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418784326

Rosiek, J. (2018). Art, agency, and inquiry: Making connections between new materialism and contemporary pragmatism. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor, & R. Siegesmund, R. (Eds.), Arts-based research (32-47). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315305073-4

van der Tuin, I. (2011). “A different starting point, a different metaphysics”: Reading Bergson and Barad diffractively. Hypatia, 26(1), 22-42. https:/doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01114.x

Notes

- That is, the shifting now of composition time.

- This is pure Haraway, though I don’t know from where.

- “Metaphorism of this sort involves phenomenal daisy chains, built of speculations on speculations as we seep farther into the weird relations between object[/thought]s [?]” (Bogost, 2012, p. 81)

- Richard, who has died: a gentle, surly, reclusive intellectual, a non-practicing academic, a non-practicing Jew, abused by his sensing of self in the minds of others, misunderstood and misunderstanding, a non-practicing lover, physically combustible and commingled, vibrantly addicted to smoke, receding from matter into matter in a New Materialist’s wetdream of entangled apartmenting. In her talk Artistry and agency in a world of vibrant matter, Bennett (2011) suggests that the hoarder is more/too perceptive of the vibrancy of matter, that hoarders are “differently abled bodies that might have special sensory access to the call of things”: Richard’s special sensory access to the call of smoke; hyper-tuned to the pain of embodiment, bookshelving the walls, three-books-deep: Latour, Larkin, Flashman, Arendt, Lacan, Proust, The Theory of Poker and of Jews, of Woolf, Graves, and Calvino, Derrida, Dewey (though no Donna). Mice comfortably reigning the kitchen, bathroom walls ulcered in weeping, pealing, breathing holes taped over in plastic that bubbled and ballooned in certain breezes moving through the apartment. Of antique lamps wrought in knotted ironing. The Incomprehensible Bed (where he labored for breath beneath the billows of mosquito netting). The aggressive dust a reclaiming entity, swallowing surfaces, clotting the gaps, and of buttons and pins in artichoke jars and yogurt containers teaming with dust-greased pennies and piles of all his life’s papers in pillars, the mattering of his life’s matters, carpets teaming with life and thoughts materialized in tightly coiled handwriting, springwriting, and lotto tickets and catalogued prescriptions in boxes and boxes and every single newspaper and magazine article in the world, and in the back of his closet, a carefully curated selection of pornography.

- “It took me no time at all to notice that this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the con-trary, it was very much occupied. It was a vast emptiness vastly filled, a nothing that found room for everything – room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far above them snow-peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world” (Harding, 2002).

Cite this Essay

Horst, Rachel. “The Treachery of Materiality: On what it’s like to be a thing.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 37, 2021, doi:10.20415/rhiz/037.e03